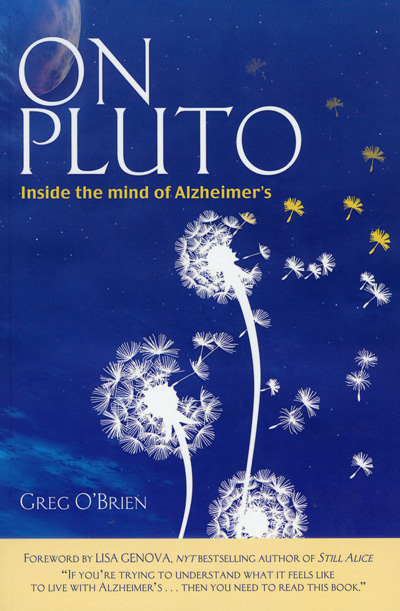

“On Pluto: Inside the Mind of Alzheimer’s” by Greg O’Brien. Codfish Press (Brewster, Mass.). 187 pp., $15.95.

A book about a man’s agonizing descent into Alzheimer’s disease could easily be steeped in negativity.

Yet in “On Pluto,” Greg O’Brien has poignantly chronicled a tragedy happening. It’s sad and joyful; depressing and uplifting; tragic and touching. O’Brien clearly expresses his rage — often using the “F-word” — at the dripping away of his brain’s power and memory, but he still has enough left to recall the good things in his life.

Tucked into O’Brien’s narrative is a subtle, nonpolemical account of how faith nurtured in a large Irish-American Catholic family has helped three generations solidify to cope with the dementia in some of its members. “We’ve got your back,” the younger generation often tells the elders.

[hotblock]

O’Brien was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s when he was 61 and wrote the book while his memory still functioned, even if in slow-motion. He combines factual information about Alzheimer’s with his practical experiences of living with the disease.

“My brain was once a file cabinet, carefully arranged in categories, but at night as I sleep, it’s as if someone has ransacked the files, dumping everything unto a cluttered floor,” writes Greg O’Brien on the effects of Alzheimer’s disease.

“My brain was once a file cabinet, carefully arranged in categories, but at night as I sleep, it’s as if someone has ransacked the files, dumping everything unto a cluttered floor,” he writes.

Once, in horror, O’Brien finds himself driving his car not knowing where he is, only to eventually figure out that instead of heading to his current home in Connecticut, he was heading toward his boyhood home in Rye, New York.

The book should be on the reading list of people with early-onset Alzheimer’s, their relatives and friends, and caregivers interested in an inside look as to what is going on inside a brain with decaying cells. But it also has value for a wider audience. In the United States 5 million people have Alzheimer’s and the number is growing as there is no cure and longevity increases.

Much of the readability comes from O’Brien’s highly skilled descriptive writing, a craft he developed over decades as a journalist, nonfiction author and head of his own communications company. The “Pluto” of the title comes from a phrase he used as a journalist when going deep off-the-record with a news source. He would say: “We’re heading out to Pluto where no one can see you or hear what is said.”

When diagnosed, O’Brien was no stranger to Alzheimer’s. His mother was already suffering from it and his maternal grandfather had it. In addition, his father was afflicted with a non-Alzheimer’s dementia. In paragraphs filled with pathos, O’Brien describes how he witnessed his mother’s brain completely succumb to Alzheimer’s while they were both sitting next to his father, bleeding in a wheelchair in an emergency room waiting to be attended.

Also in his mind though are touching anecdotes such as the first kiss shared with the woman who would become his wife while her overprotective brother was sleeping in another room.

But O’Brien can still look to the future with hope, the possibility that his mother is waiting on Pluto and beyond because memory isn’t all it’s cracked up to be: “While memory offers delineating context and perspective, it doesn’t define us. Definition is found in the spirit, in the soul, but one must dig for it.”

***

Bono is a retired CNS staff writer.

PREVIOUS: ‘Beyond the Lights’ offers shadowy view of sexuality

NEXT: ‘Jane the Virgin’ series thoughtful, yet troubling look at family, love

I still know the rosary and all the beautiful mysteries. This is a terrible disease. I think God has given us this disease to bring families together. Love & prayers Paul