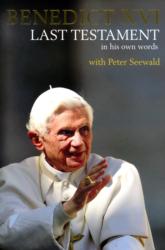

“Last Testament: In His Own Words”

“Last Testament: In His Own Words”

by Pope Benedict XVI with Peter Seewald.

Bloomsbury Continuum (London, 2016).

257 pp., $24.

Peter Seewald’s interview of Pope Benedict, which follows from previous interviews and works including “Salt of the Earth,” offers readers a journey through the theological life of the retired pope. This includes thoughts on significant individuals such as Jesuit Father Karl Rahner, Father Hans Kung and St. John Paul II.

The first part of the book highlights a world radically different from our own, that of Bavarian Catholicism in the mid-20th century. Its piety centered on family, village and Christ.

Joseph Ratzinger stepped out of this world into the seminary and then higher theological studies in Munich. He relished this world.

[hotblock]

Though the Nazi and immediate postwar eras brought deep change, the pontiff explains how the faith endured: “Despite the intrusiveness — where the atmosphere of war was still somehow in the air — there was a joy that we were now together. The being with one another, the encountering each other, the companionship, was subsequently something deeply moving for me in my consciousness” Such words also convey the sense of connection that people enjoyed back then, with a shared sense of place and belief.

Readers of “Last Testament” meet the lecturers who impacted the future pope, such as professor Georg Angermair, whom Pope Benedict qualifies as someone who rejected 19th-century pieties, a common practice of the time. As a seminarian, Ratzinger like so many of his classmates, it seems, wanted something fresh.

Progressivism comes up many times in the book regarding his pre-Second Vatican Council, conciliar, and postconciliar experiences. Pope Benedict never denies his progressiveness. He notes that “progressive” meant something different from the Kung perspective, something that always remained faithful to the deposit of the faith.

In this sense, Pope Benedict sounds like a typical forward-oriented 20th-century thinker, along the lines of fellow personalist St. John Paul: “I didn’t want to operate only in a stagnant and closed philosophy, but in a philosophy understood as a question — what is man, really? — and particularly to enter into the new, contemporary philosophy. In this sense I was modern and critical” While Cardinal Ratzinger shared St. John Paul’s personalist viewpoint, the former’s Augustinian roots provide an alternative view to his predecessor’s Thomism, this interview clearly shows.

The interview also highlights philosophy’s key role in the pontiff’s spiritual and theological journey, including the importance of ancient Greek philosophy and its symbiotic relationship with theology, but extending to later thinkers such as Pascal. As at many points in the book, the pontiff here conveys the harmonious whole of the Catholic faith.

[hotblock2]

“Last Testament” includes many of the pope’s thoughts on the nature of the church. He ties this in with the office of the papacy: “I, too, always wanted the local churches to be active in and of themselves, and not so dependent on extra help from Rome. So the strengthening of the local church is something very important” Words such as these portray a much softer and more flexible person than the one portrayed in the media or by certain theologians.

Though he says that he never pursued power, he met and worked with the most powerful Catholic thinkers and leaders of the past 60 years. He calls Swiss theologian Father Hans Urs von Balthasar and French Jesuit Father Henri de Lubac his favorite theologians, recalls working with Father Rahner at Vatican II, and teaching with noted philosopher Josef Pieper at Munster, Germany. Pope Benedict qualifies Pieper and himself as progressives before adding: “Only later did he go in the same direction as I did, and Lubac. We saw that the very thing that we want, something new, is being destroyed. Then he (Pieper) energetically opposed it.” Such words convey the simplicity and clarity of Pope Benedict’s view of Vatican II and its aftermath. Readers also see the consistency in his thought.

The pope’s serenity clearly comes from trusting in God. His answers never convey defensiveness, even concerning Vatileaks or the abuse scandals. Benedict is humble, as when he acknowledges Father von Balthasar’s intellectual superiority. Regarding the present, he expresses great confidence in Pope Francis. Above all, Benedict’s critics will be surprised at his open-mindedness, which is the openness of someone who is confidently anchored in his beliefs and carries no secrets.

***

Welter has degrees in history and theology, and teaches English in Taiwan.

PREVIOUS: Retrospective of original Donald Duck comic book artist fills the bill

NEXT: With keen sense of purpose, a dog keeps coming back to his people

Share this story