Fr. Lance Nadeau teaches Africans about growing and harvesting crops. (Photo courtesy of Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers)

When Father Lance Nadeau was a newly-minted member of Maryknoll (the Catholic Foreign Mission Society of America), he indicated to his superior that his preference would be a missionary assignment in Japan.

“You will never see Japan,” was the flat reply.

In that moment, Father Nadeau could well appreciate Jesus’ words Peter: “Someone … will lead you where you do not want to go” (John 21:18).

That’s exactly what happened. Far from the land of the rising sun, Father Nadeau has ministered almost entirely in the African continent, to his great joy.

Now 71, Father Nadeau came to his vocation somewhat late. As a young man, becoming a priest was not high on his to-do list, let alone becoming a missionary. Born in 1947 in Greenfield, Mass., Father Nadeau and his family eventually relocated to Philadelphia and joined St. Martin of Tours Parish.

He was familiar with Maryknoll through its monthly magazine, which was usually on the family coffee table, and of course through the mite boxes the order distributed each Lent. Yet these nudges did not register as a possible vocation. After receiving his B.A. in philosophy from Fairfield University, he did a four-year hitch in the U.S. Navy as a medic assigned mostly to the Marines at Quantico.

[hotblock]

As so often happens with young people, religion took a back burner during that stage of his life, but it definitely had a re-awakening when he returned to civilian life. He continued his education, earning a Ph.D. in religious studies at Temple University, and went on to teach at Villanova University and Rosemont College.

When he ultimately chose the priesthood, Father Nadeau found himself deeply influenced by the life of Maryknoll Father Joseph Sweeney, who spent 30 years in China and Korea working with lepers, until he was placed under house arrest and deported by the communists.

Father Nadeau entered the Maryknoll order in 1983, and after his formation — which included a second doctorate, this time in missiology from the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome — he was ordained in 1990. Since then, he has ministered in Tanzania, Egypt, Bangladesh and, since 1999, Kenya.

For part of his career, Father Nadeau has worked closely with people suffering from AIDS.

“When I came here, the infection rate was about 14 percent of the population,” he said in a telephone interview. “In some areas, it was even higher, and people were scared to death of it. You would find people abandoned by their families and dying in the streets. Anti-retrovirus drugs have made a difference and that’s a great blessing.”

During his ministry, Father Nadeau also served a six-year term as the Maryknoll Africa Regional Superior, but he admits that he prefers working directly with the people, not as an administrator.

For most of his tenure in Kenya, Father Nadeau ministered at Kenyatta University, a school of 72,000 students over multiple campuses.

If you think of Kenya as a mission country, think again. As a percentage of the population, there are more Catholics there than in the U.S., and most go to church.

“I don’t think you would call this a secularized society,” Father Nadeau said. “People take their faith and religion very seriously. The rate of church attendance is very high, and at the university, 95 percent of Catholics attending are under 25.”

Father Nadeau added that the faith is not simply due to youthful fervor.

“Many of them come back after they graduate to be married or to have their children baptized,” he said. “You have to get to church 20-30 minutes early to get a seat.”

The university is home to a number of Catholic youth groups that are committed to various social justice causes, ranging from health care to women’s empowerment.

“Some go out as missionaries to marginal areas of Kenya near the South Sudanese border and the Ethiopian border,” Nadeau said.

Over the years, the role of Maryknoll and other foreign mission societies has changed, a shift that traces back to goals and strategies instituted by Pope Benedict XV and Pope Pius XI in the early 20th century, Father Nadeau explained.

“The plan was to establish and build the local church,” he said. “With God’s help that’s exactly what we did, and things began to change in the 1970s, when foreign missionaries began to turn over parishes and administration of dioceses to the local church, and the local church began to take a leadership role. Now the missionaries are in specialized ministries such as HIV, spiritual direction and social communications.”

Father Nadeau said he’s content in his more targeted mission.

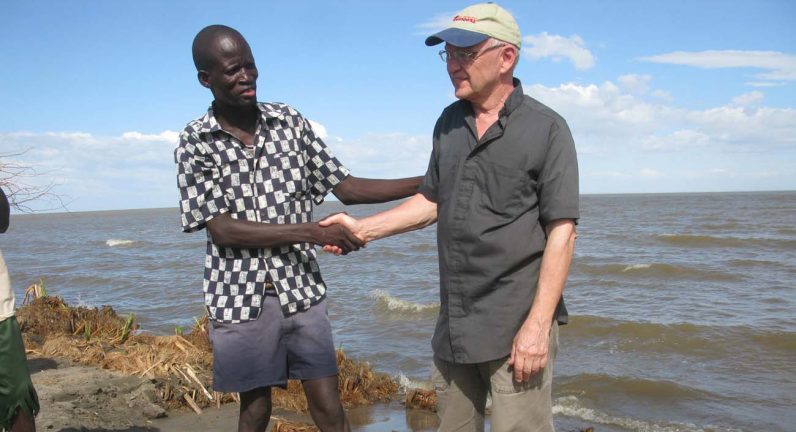

Water is a precious commodity in Africa. Fr. Lance Nadeau works closely with residents to teach them to effectively and carefully utilize water for their crops and for drinking, and the people appreciate his friendship. (Photo courtesy of Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers)

“I always liked parish ministry but we don’t do that now.” he said. “Being a chaplain at a university is like parish ministry, except the turnover rate is every four years.”

He estimates that during his time at Kenyatta University, where he lived until this past year, about 80 men pursued a call to the priesthood. Most of them have persevered, he believes.

The Maryknoll order has itself changed. Until recently, its candidates were with few exceptions drawn from the U.S. Now it has begun to accept aspirants from the countries where it serves.

“I think it will make Maryknoll a more relevant institution,” Father Nadeau said, adding that “everybody is from a mission land.”

Over the years, Father Nadeau could have come back to the U.S. on furlough for a few months annually, but he generally stayed for just a few weeks at a time. During his most recent visit, he realized just how much Kenya was in his blood.

“I arrived in Philadelphia in March in the middle of a blizzard and stayed with my sister in East Norriton,” he said. “I was freezing, I didn’t know how to turn on the television and I didn’t want to drive.”

Now he’s back in Kenya and content.

”God has been very good to me,” he said. “The happiest days of my life were working at Kenyatta University and I have never, ever regretted my days as a priest. I feel blessed and sanctified.”

PREVIOUS: Once hostile to faith, doctor and deacon shares how to work for God

NEXT: Catholic senior centers help older adults stay healthy, connected

I’m glad to read about Fr. Lance here. At Kenyatta University in Nairobi, Kenya, Fr. Lance’s homilies nourished me and tens of thousands of other students. Scripture moulds, fashions and patterns us on the identity of Jesus Christ of Nazareth. Christ becomes present vividly through the example of the Maryknoll missionary priesthood and person of Fr. Lance of Philadelphia, USA. AMDG.

I’ve met priests like Father Nadeau in Africa and seen their work up close. They are truly inspiring people! They face incredible challenges but they still do great work.