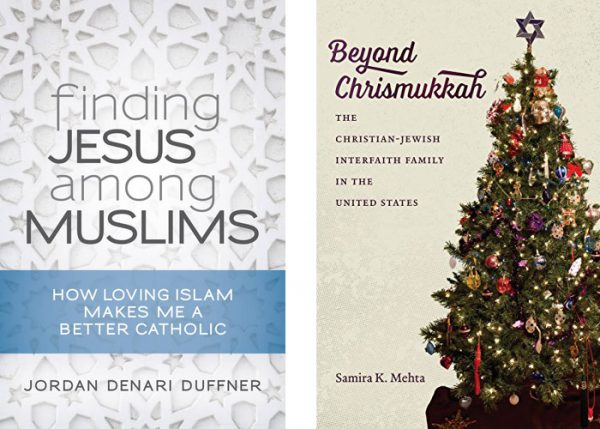

“Finding Jesus Among Muslims: How Loving Islam Makes Me a Better Catholic”

by Jordan Denari Duffner.

Liturgical Press (Collegeville, Minnesota, 2017).

130 pp., $19.95.

“Beyond Chrismukkah: The Christian-Jewish Interfaith Family in the United States”

by Samira K. Mehta.

University of North Carolina Press (Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 2018).

260 pp., $27.95.

Lutheran Bishop Krister Stendahl, a pioneer in ecumenism, famously offered three rules for interfaith dialogue: 1) When trying to understand another religion, ask the adherents of that religion and not its enemies. 2) Don’t compare your best to their worst. 3) Leave room for “holy envy.”

These attitudes admirably inform Jordan Denari Duffner’s beautifully written and deeply felt “Finding Jesus Among Muslims.” It is a timely and important book that offers a quiet but forceful rebuttal to the current demonization of Muslims.

[hotblock]

Duffner presents a mosaic of Islam, drawn from personal relationships, anecdotes, study, theology and practice. “Islam has helped me respond to God’s call in my life. It has helped me be more attentive to the way God operates in the wider world and in the lives of my Muslim friends, but also how God is present in the faith tradition I grew up in. Islam makes me a better Catholic.”

This book directly challenges stereotypes that equate Islam and violence and is frank about the depth of Islamophobia, including among Catholics. Many years of personal and professional experiences have convinced her that “dialogue is not simply a matter of knowing of, or being around, people who are different from us. Dialogue is a way of being around, a disposition of being in relationship with others.”

The book includes a number of helpful appendices: discussion questions for each chapter, resources for further study, an excellent glossary and guidelines and resources for dialogue with Muslims. These features make “Finding Jesus Among Muslims” particularly valuable for parish or school groups. It is a book of sanity in this difficult time and deserves a wide audience.

Samira Mehta writes about the most intimate of interfaith experiences, that of marriage, family and personal religious identity. Mehta, an assistant professor of religious studies at Albright College, has a fluent style that makes academic studies easily accessible to a lay audience. The book is rich in detail, ranging from in-depth conversations with interfaith families, discussion of institutional attitudes on intermarriage, depictions of interfaith marriage in children’s books and visual media (including “Abie’s Irish Rose,” “Bridget Loves Bernie,” “Annie Hall”) and culture (food, cooking, religious objects and home-based religious rituals).

[tower]

In earlier decades interfaith marriages and threats of assimilation raised acute questions of Jewish identity, which led Reform Judaism to embrace patrilineal descent as proof of Jewishness. (Historically Jewish identity came from matrilineal descent, a position that is still held by more traditional Jewish denominations. The child of a Jewish father in an interfaith marriage would need to convert if they chose to embrace Judaism.) Efforts to encourage single-faith homes were based on the conventional wisdom “that enforced the idea that Judaism was an all-encompassing civilization while Christianity was acceptance of a particular religious belief.”

Mehta illustrates the lived experience of interfaith families in light of contemporary sociological and theological changes. “Two trends allowed interfaith families to draw selectively from their Christian and Jewish backgrounds in order to create a mosaic of household practices that formed new, hybrid identities: the development of a ‘seeker’ mode of religion and the rise of multiculturalism as a theoretical and lived concept intersected with a consumer-based mode of identity formation to create new possibilities for interfaith families.”

Over time, the experience of blended families has moved into more complex religious choices and identities, especially in interracial families. Because they make distinctions between official theologies and cultural traditions, they have been able to “move the conversation away from competing truth claims and religious affiliations and toward a multicultural approach to identity.” They develop “a cohesive family narrative … beyond denominational constraints.”

In her concluding chapter Mehta presents case studies of four interfaith families. “Being the child of interfaith marriage and an inherently interfaith individual became a distinct way of being in the world, in which a worldview was drawn from the interplay of practices and intellectual histories.”

The deft presentation of broad ranging material and in-depth interviews makes this an important and thought-provoking study of a unique and vibrant religious experience. These unique religious histories can be read as a partial antidote to a culture of growing sectarianism and tribalism.

***

Linner, a freelance writer and reviewer, has a master’s degree in theology from Weston Jesuit School of Theology.

PREVIOUS: More underlies ‘The Upside,’ than just two guys having fun

NEXT: Priest-author tells story of Catholicism in the American heartland

Share this story