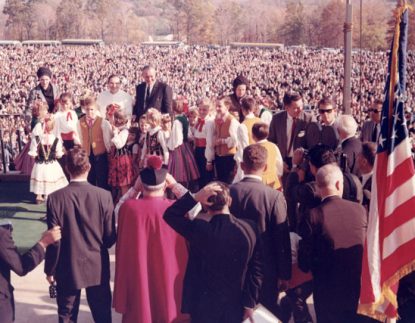

The presence of President Lyndon B. Johnson helped draw national media attention to the Oct. 16, 1966 dedication of the National Shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa in Doylestown, attended by thousands of Polish American faithful.

Fifty years ago this month — on Oct. 16, 1966 — Polish American Catholics from the Archdiocese of Philadelphia and beyond came together in Doylestown, Bucks County, to witness the dedication of the newly constructed National Shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa.

As we celebrate Polish American Heritage Month, the history of the shrine offers a reminder of the faithfulness of American Polonia and its members’ contributions to building up the Catholic Church in the United States.

The dedication of “American Czestochowa,” as the shrine has come to be known, was without doubt a momentous occasion. Among those who addressed the crowd was President Lyndon B. Johnson, whose presence helped draw national media attention to the event. He spoke glowingly about the beauty of the building and the “spirit of Polish-Americans” it enshrined.

Those in attendance had every reason to be proud. Not only was the dedication of the shrine the fulfillment of a dream that had been many years in the making, it also marked an especially momentous milestone for those of Polish descent. The completion of the building was timed to coincide with the one 1,000th anniversary of the Christianization of Poland in 966.

[hotblock]

The vision for an American Czestochowa came from Father Michael Zembrzuski (1908-2003), a member of the Pauline Fathers, a religious order whose monastery in Czestochowa, near Krakow, had been entrusted with the care of the icon of the Black Madonna.

In 1951 he came to the United States to serve as a missionary after he and other members of his community had been expelled from Hungary by the Communist government.

Pilgrims at the shrine visit a statue of the most recently canonized son of Poland, St. John Paul II. (Photo by Sarah Webb)

After serving among various Polish parishes for two years, Father Zembrzuski secured permission in 1953 to purchase a 40-acre tract of land near Doylestown and establish a monastery. The site included a small barn, which he converted for use as a chapel dedicated to Our Lady of Czestochowa. His desire was to make the monastery and chapel a site of pilgrimage and devotion, just like its counterpart in Poland.

A few years later, Father Zembrzuski increased the size of the property by purchasing a neighboring hilltop that reminded him of Jasna Gora, or Bright Hill, the location of the Czestochowa monastery in Poland.

He dreamed of drawing thousands annually to a place where Polish-American Catholics could share their rich spiritual heritage with the rest of the nation, with the hope that Czestochowa will one day “be as well known as the Blessed Virgin of Lourdes, Fatima, Guadalupe, Einsiedeln and other miraculous places.”

Father Zembrzuski’s desire to establish the shrine and promote the cult of Our Lady of Czestochowa was also borne out of Cold War concerns over the loss of religious freedom in Eastern Europe. He spoke explicitly of the project as one that would forge a “spiritual link” between American Catholics and the “Church of Silence” behind the Iron Curtain and help ensure that “Godliness will prevail.”

Even though Father Zembrzuski started out with only $56 to his name, the project generated immense support among Polish Americans from across the country. As development commenced, individuals and groups were encouraged to come to the shrine site during the pilgrimage season that ran from May to October so that they might “witness the progress being made” and “find spiritual regeneration at the foot of the altar of Our Lady of Czestochowa.”

Many visitors came for one-day retreats, often organized through Polish parishes and fraternal organizations. The Union of Polish Women in America, for instance, had since 1956 organized an annual gathering for its members on the fourth Sunday in May.

Others came by chartered bus to attend Mass, pray the rosary and engage in other devotions. While at Czestochowa, they were also encouraged to take advantage of the picnic areas and wander around the monastery grounds.

[hotblock2]

Since its dedication in 1966, American Czestochowa has drawn millions of visitors who have sought to honor Mary and seek her favor. Yet the ongoing popularity of the shrine stems from the larger role it plays for members of the Polish-American community.

Not only does it provide a place for Polish-American Catholics to worship together in their native language and preserve their distinctive religious practices, it has also become an increasingly important custodian of Polish cultural identity with its festivals and other events.

In many ways, Czestochowa serves as a Westminster Abbey for American Polonia, a place to enshrine the history of a people and honor their memory. Throughout the shrine, there are countless memorials to benefactors and numerous tributes to important church leaders and Polish dignitaries.

The shrine grounds also contain an extensive cemetery, which includes an honor section for distinguished Polish-Americans and a veteran’s section for those who served in the Polish or American armed forces.

Now 50 years later, the shrine at Doylestown continues to provide for the spiritual needs of American Polonia. In recent years, they have built a retreat center and promoted prayer to the Divine Mercy and Poland’s most recently canonized saint, Pope John Paul II.

The shrine’s history provides a testament to Polish-Americans’ deep devotion to Our Lady of Czestochowa and their desire to share their spiritual gifts with the nation.

***

Thomas Rzeznik is an associate professor of history at Seton Hall University and vice-president of the American Catholic Historical Society. A fuller version of this article appeared in the society’s journal, “American Catholic Studies.”

PREVIOUS: Pope Francis bestows honors on 46 Philadelphians

NEXT: Archbishop announces clergy changes in archdiocese

Share this story