A window from the now-closed Ascension of Our Lord Church in Philadelphia depicts the Presentation of Jesus in the temple. The window is destined for the soon-to-be-built Cathedral of the Holy Name of Jesus in Raleigh, N.C.

The decision last September by the Archdiocese of Philadelphia to close Ascension of Our Lord Parish in the Kensington section of the city was saddening but absolutely necessary.

The once huge parish with more than 13,000 congregants had dwindled to less than 200 weekly worshippers and its majestic church was beyond repair.

Like so many churches in the city built in a bygone era by ordinary blue collar working families who have long since moved away, Ascension had magnificence worthy of a cathedral in most dioceses.

[hotblock]

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if such churches could be moved to dioceses that need them? That can’t be done, of course, but in Ascension’s case its beautiful stained glass windows will receive new life in a new cathedral.

The Diocese of Raleigh, North Carolina, which was founded in 1924 with just 8,200 Catholics, has grown to the point where there are now an estimated 500,000 Catholics within its borders, according to Bishop of Raleigh Michael Burbidge. It also has the tiniest cathedral in the lower 48 states (Juneau, Alaska’s is even smaller), he explained, with a seating capacity of just 300.

The need to replace Sacred Heart Cathedral was discussed for years, and it was shortly after Bishop Burbidge took up his duties as Bishop of Raleigh in 2006 that serious studies for a new cathedral were undertaken.

The future Holy Name of Jesus Cathedral and its supporting buildings will be located on a 40-acre campus, which is part of a larger tract, originally purchased in the 19th century by Father Frederick Thomas Price, the first priest ordained in North Carolina and a co-founder of the Maryknoll Fathers.

The entire project will cost an estimated $65 million to $70 million, Bishop Burbidge said, and of that sum $52 million has already been pledged without any mandate to the parishes.

“We are not assessing the people in the parishes and we are not going into debt,” he said. “The final amount raised will determine what we can do at this time, but the priority will be the cathedral itself.”

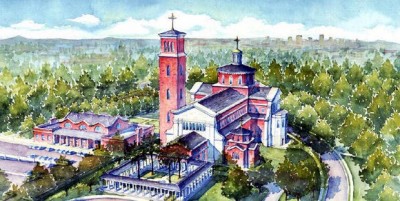

An artist’s rendering shows the planned Holy Name of Jesus Cathedral in the Raleigh Diocese, home to the magnificent stained glass windows from Ascension Church in Philadelphia.

At this time the architectural plans for the neo-classical cathedral have been drawn up, and groundbreaking will probably take place within a year, with occupancy perhaps three and a half to four years from now.

The availability of the Ascension windows is providential, believes Bishop Burbidge, who is a former auxiliary bishop of Philadelphia and rector of St. Charles Borromeo Seminary.

“A couple of my priest-friends in Philadelphia made me aware the windows would be made available and they were of such magnitude, the size of them is really cathedral-like,” he said.

He sent a diocesan representative along with the architect of Holy Name of Jesus, James McCrery, to Philadelphia to inspect the windows. What they found was breathtaking – a set of 42 brilliantly colored windows, some as tall as 17 feet 8 inches and more than 4 feet wide, just about perfect for the new cathedral. Because it has not yet been built, the plans could easily be altered to accommodate the windows.

It is not unusual for stained glass windows of closed churches finding a new home in another newer church, but the size of this matched collection is rare indeed.

Most were executed in neo-Gothic style in 1927 by German-born Philadelphia artist Paula Himmelsbach Balano, the first woman in America to own her own stained glass studio. Six others, in complementary style, were crafted by J.M. Kase & Company in Reading.

A sale was negotiated for the windows for $320,000. That is only the beginning. Stained glass windows need periodic refurbishment, and in the case of the Ascension windows it was long overdue. Germantown-based Beyer Studio has been contracted to fully restore the windows, which means carefully taking them apart piece by piece, making any necessary repairs, and resetting them in new leading.

A worker from Beyer Studio, in Germantown, removes a panel of a stained glass window from Ascension Church.

Beyer Studio works closely with the Philadelphia Archdiocese to create new windows but especially with restoration of older ones. There is not an exact figure for what it will cost to refurbish the windows, ship and install them, but Bishop Burbidge estimates it could go as high as $1 million.

Whatever the final figure is, it is but a fraction of what it would cost to create new windows of that quality and size. At this point, a relatively small window weighing 200 pounds depicting the Adoration of the Magi has been restored and is on display in a light box at the Catholic Center in Raleigh.

Churches such as Ascension “were built by incredible sacrifice on the part of the people, but because of their faith they wanted to give to God,” Bishop Burbidge said. “We know these people in one way or another because they are our ancestors.”

The Church, he said, “continues to grow but in different places. Now it is in the South, but we cannot forget all of those people who laid the foundations for us. We think the acquisition of these windows reinforces that idea.”

(See many more images of the windows and Ascension Church, and read about Beyer Studio’s restoration of the windows for the Raleigh cathedral on Beyer’s blog for the project.)

Share this story