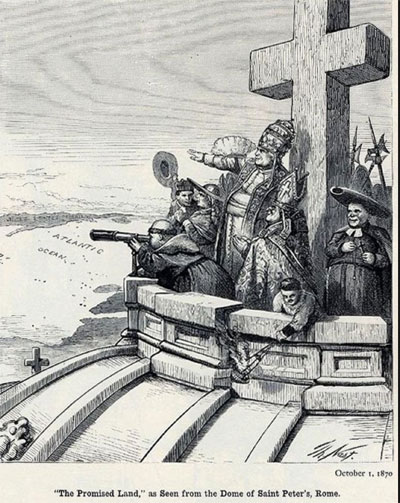

A cartoon by illustrator Thomas Nast in 1870 reflected fears by some Americans that the papacy might seek to expand its power in the United States. (Courtesy American Catholic Historical Society)

Plans for road closures and security perimeters have left many feeling like the city will be under siege when Pope Francis comes to visit at the end of September. Listening to some folks talk, Philadelphia seems to be getting ready for a full-scale papal invasion.

But whatever the inconveniences might be, excitement abounds. The city and the nation are getting ready to offer the pope the warmest of welcomes. That, in and of itself, is quite remarkable given the way that many Americans would previously have reacted to such news. Hard to believe, but there used to be a time when the very thought of a papal visit to the United States would have been cause for alarm.

For much of the 19th century, anti-Catholic hostility was fueled in part by a belief that the Vatican was plotting to take over the country and subvert our democratic institutions.

Contributing to the 1844 Nativist Riots here in Philadelphia, for instance, were rumors that Catholics, under order from the pope, were working to have the Bible removed from public schools. The “Bible defenders” saw the need to rally to protect the country from foreign “Popish banditti,” as one broadside asserted.

But perhaps no one depicted these alarmist views better than Thomas Nast, the political cartoonist famous for his critiques of New York City’s Tammany Hall political machine. In an 1870 cartoon titled “The Promised Land,” he depicted the pope standing atop the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, which he made to look like a ship’s crow’s nest. From that vantage point, the pope and an entourage of clerical minions look across the Atlantic to American shores with an eye for conquest.

[hotblock]

As irrational or even absurd as such depictions may now seem, they had grounding in the political realities of their day. At the time Nast’s cartoon was published, the Vatican itself was under siege. The capture of Rome by Italian nationalist forces in September 1870 brought an end to the Papal States and the temporal power of the papacy. Trounced in Europe, would the pope look to reestablish his power in the United States, where the church was growing in number and might?

Catholics and non-Catholics alike followed the “Roman Question” intently. Those critical of the papacy saw the “liberation” of Rome as the triumph of liberty and democracy over and against papal absolutism. Those faithful to the pontiff saw him as a “prisoner” to radicals and heeded calls to pray for his restoration.

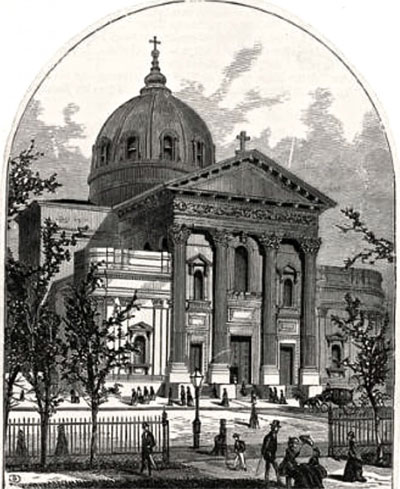

An 19th century lithograph shows the Cathedral of SS. Peter and Paul in Philadelphia, which was the site of an 1870 rally for thousands of Catholics supporting the pope.

Some went further. In December 1870, several thousand Philadelphia Catholics gathered at the cathedral for a mass meeting to protest the “spoliation of the Holy Father” and the “invasion of the Holy See.” The event did little to change the situation in Europe, but it certainly demonstrated Catholic allegiances.

In response to these political developments, Catholics began to forge stronger ideological attachments to the papacy over the course of the late 19th century. Even if not preparing for an outright papal invasion, they came to emphasize the spiritual authority of the pope much more ardently than before. He was the visible head of the church and their “spiritual sovereign.” The declaration of papal infallibility at the First Vatican Council in 1870 reinforced the point.

Other things also helped make the pope a much more central figure in the Catholic imagination. Lithography and mass-produced printing allowed images of the pope to circulate widely. Portraits of him found places of honor in churches, schools and homes. Prior, few Catholics would have known what the pope even looked like! Now, the pontiff became an identifiable person.

Ordinary Catholics’ spiritual connection to the pope likewise deepened. Prayers for the Holy Father and his intentions became a regular feature of Catholic devotional life, often as a requirement for indulgences. In 1884, under Pope Leo XIII, prayers for the Holy See, known as the Leonine Prayers, were added for recitation after low Mass. People also sought out medals, rosaries, and other religious goods blessed by the pope.

Taken together, these prayers and practices had a powerful effect. As historian James McCartin has remarked, they allowed Catholics to incorporate “formal displays of allegiance to the pope into their religious life.” Loyalty to the pope became a visible hallmark of Catholic identity.

The pope today may not wield the type of power people once feared, but there’s no denying his influence. And there’s no telling what’s in store now that Pope Francis has set his sights on the United States. We may very well find ourselves on guard for some surprises!

***

Thomas Rzeznik is associate professor of history at Seton Hall University.

***

Want to learn more? The American Catholic Historical Society (263 South Fourth Street) is hosting an open house on Sunday, Sept. 13 from 1 to 5 p.m. to premier their newest exhibit, “Before Francis: Popes, Pilgrims and the History of Philadelphia-Vatican Ties.” The event is free and open to the public. For more information visit www.amchs.org.

Share this story