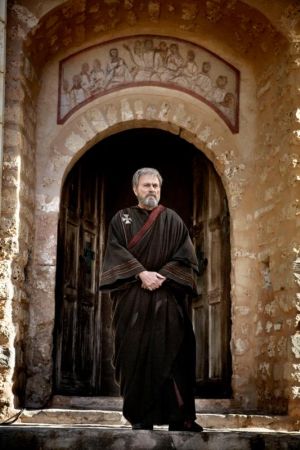

Franco Nero portrays St. Augustine as an old man in a scene from the movie “Restless Heart.” Sts. Ambrose and Augustine both are remembered today as invaluable Fathers of the Church. (CNS photo/Maximus Group)

St. Augustine was a long way from his northern-Africa homeland when Milan’s Bishop Ambrose baptized him at dawn on Easter in the year 387.

His baptism climaxed one of the greatest conversion stories ever. Augustine arrived at the baptismal font only after an agonizing process of deliberation.

St. Ambrose, the baptizer that day, was an esteemed preacher and a force to reckon with at a tumultuous time in the imperial city of Milan, then serving as the seat of the Roman Empire’s Western emperor.

Augustine, 33 years old, was a teacher of rhetoric, the art of persuasive public speaking. He hailed from a region located in today’s Algeria.

Little was it known then that Ambrose was baptizing someone destined to be ranked forever among Christianity’s greatest thinkers and writers, the author, for example, of classics like the “Confessions” and “The City of God.”

Sts. Ambrose and Augustine both are remembered today as invaluable Fathers of the Church.

Augustine’s journey to baptism began as a child when his mother, St. Monica, enrolled him as a Christian catechumen. But his baptism was delayed into the future, not an uncommon practice at the time.

The youthful Augustine wrestled with issues of belief, especially their implications for behavior. He wound his way among Christians, semi-Christians and other believers of his fourth-century world.

[hotblock]

For him, a journey toward baptism entailed struggling to decide what kind of man he wanted to be.

Given the challenges of his often painful faith journey, it is unsurprising that the first lines of his “Confessions” include the famous words, “Our heart is restless, until it rests in you (Lord.)”

The journey that ultimately led Augustine to Milan began in 383 when he traveled from northern Africa to Rome to accept a position as a teacher of rhetoric. His Rome position proved dissatisfying to him, however.

So in 384 he accepted a similar position in Milan. There our rhetoric teacher encountered Ambrose, the gifted speaker and preacher. It surprised Augustine that he was impressed by Ambrose’s oratorical skill.

Equally surprising for Augustine, perhaps, was the positive attitude toward Scripture, particularly the Old Testament, that Ambrose engendered in him.

Ambrose’s available time for conversation, however, was limited. Not only did he devote considerable time to study, but he labored under pressures exerted by imperial authorities.

For Milan at this time was the seat of a teenage emperor, Valentinian II, whose imposing mother Justina was an Arian Christian. As such, she believed that God the Father created Jesus Christ and not, as the Nicene Creed holds, that God the Father and the Son are one in being.

During Augustine’s time in Milan, Justina attempted to seize churches from Ambrose for use by the Arians. In this heated atmosphere, Ambrose showed himself a strong leader by standing up to her imperial recklessness.

Ambrose is remembered in church history for stating flatly, “The emperor is in the church, not above it.”

Less than a year before his baptism Augustine had what people today might term “a religious experience.” He felt called to read a passage in St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans (13:13-14) that convinced him to change his lifestyle and “put on the Lord Jesus Christ.”

He was moved profoundly. Finally he could accept baptism.

Preparing for baptism by Ambrose meant enrolling in a demanding process of instruction involving two sessions daily on each Lenten weekday, for an amazing total of 60 sessions, according to “Font of Life,” by Garry Wills, a scholar of Augustine.

Ambrose clearly accorded huge importance to baptism.

When the newly baptized Christians emerged from the baptismal waters, they donned white gowns that signified putting on Christ’s new life and were worn for the week ahead. Wills explains:

“When the baptizands come from the water, Ambrose says, it is like Christ coming from the tomb: ‘Since baptism is like death, surely when you are submerged and re-emerge (from the water) this is like a resurrection.'”

(Gibson served on Catholic News Service’s editorial staff for 37 years.)

PREVIOUS: The Fathers of the Church and the Bible

NEXT: The Fathers of the Church: Who they are and why they matter

Share this story