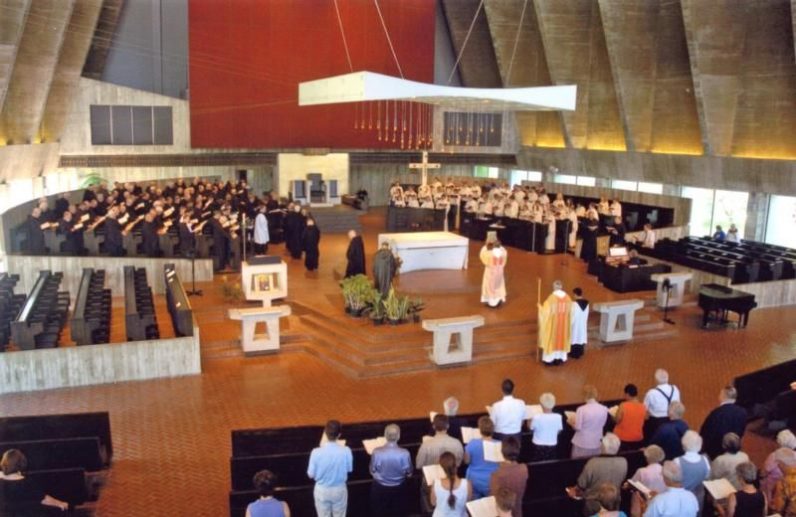

St. John’s Abbey and University Church in Collegeville, Minn., reflects how a church’s very design can foster unity and encourage participation among everyone present during celebrations of the Mass. Contemporary architects frequently “have constructed churches which are both places of prayer and true works of art,” St. John Paul II noted in his 1999 “Letter to Artists.” (CNS photo/courtesy St. John’s Abbey).

A simple, white-granite altar, together with the crucifix and striking white baldachin suspended above it, catches and holds the eye as soon as one enters the remarkable church constructed in the early 1960s at St. John’s Abbey and University in central Minnesota.

In planning this church, its Hungarian-born architect, the widely known Marcel Breuer, and members of the abbey’s Benedictine community, known for expertise and leadership in all things liturgical, confronted a key question.

Could a way be found, through the church’s very design, to foster unity among everyone present during celebrations of the Mass and to encourage their full participation in the liturgy?

The church opened in the fall of 1961, not long before the promulgation late in 1963 of the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy. It asked that “great care” be taken when churches are built “that they be suitable for the celebration of liturgical services and for the active participation of the faithful.”

[hotblock]

Those present for celebrations of the Mass “should not be there as strangers or silent spectators,” the council declared. “Full and active participation by all the people” is the aim.

When you think of artists serving the church, architects might not be the first to come to mind. But they came to mind for St. John Paul II in his 1999 “Letter to Artists.”

An artist’s work has the potential to reflect God’s creative work, he suggested. It was particularly the beauty created by artists that captured the pope’s attention.

“It can be said that beauty is the vocation bestowed on (the artist) by the Creator in the gift of ‘artistic talent,'” a talent that ought to “bear fruit,” he wrote. Among the artists mentioned were poets, painters, sculptors, architects, musicians, actors and others.

I confess that I am partial to the church at St. John’s and to its uniquely simple beauty. My 1963 class at the university the monks run was the second to graduate in the new church.

Years later when I participated in Sunday Mass there, I felt that the underlying purpose of the Liturgy of the Eucharist still to come was made plain when several monks came forward after the homily “to set” the Lord’s table at the main altar.

[hotblock2]

Of course, the church’s interior architectural design drew all eyes to this action at the altar. No columns obstruct one’s view of the altar, or the monastic choir, or the congregation. The floor plan, with its trapezoid-like shape, lends itself to pulling the assembled community together and making it one.

Thus, it aids worship by nurturing a sense that those participating in the liturgy are bonded both to God and to each other.

Contemporary architects frequently “have constructed churches which are both places of prayer and true works of art,” St. John Paul noted in his “Letter to Artists.”

The church, he told them, needs artists, needs them to “make perceptible, and as far as possible attractive, the world of the spirit, of the invisible, of God.”

***

Gibson served on Catholic News Service’s editorial staff for 37 years.

PREVIOUS: Lectio divina: Discovering art as an aid to worship

NEXT: How did the Jews and Romans react to Jesus’ resurrection?

Share this story