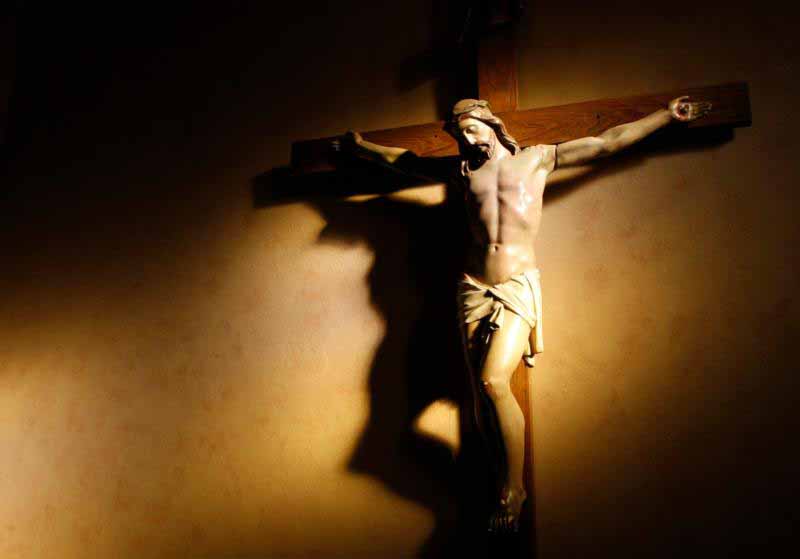

Evening light shines on a crucifix in the vestibule of St. Paul’s Basilica in Toronto in this 2008 photo. By recognizing the great status of Holy Week and Easter, the ancient church made it clear how important the liturgy, “the work of the people,” is for us all. (CNS photo/Nancy Wiechec)

“If Christ has not been raised, your faith is in vain,” wrote the apostle Paul (1 Cor 15:17), proclaiming the resurrection of Jesus to be the most important element of the faith. And such an important event would deserve a kind of memorial.

The majority of the first Christians expected the world to end almost any day, and so there was no great need for feast days. Most initial Christians were converted Jews who reverenced the Old Testament and thought the way to be a good Christian was to follow the Jewish law.

Rather obviously, the world did not end, and by the year 150, most Christians were Gentiles, including bishops, who wanted specifically Christian feasts with liturgies centered on Sunday and not the Sabbath, the holy day of the Jews.

[hotblock]

Those wanting to retain the Jewish reckoning lived mostly in the Eastern Mediterranean while those wanting to use a more general reckoning lived in the gentile world and especially in Rome.

An important element separating these two groups was that the Jews used a lunar calendar, so there was no way to synchronize the two calendars.

The defenders of the old way said that the resurrection should be observed on the 14th day of the Jewish month of Nisan, a date derived from their interpretation of the Gospel crucifixion narratives, and their opponents called them the “Fourteeners.”

Sadly, the struggle became fierce because the entire Christian calendar depended upon the results. The main proponent of the new date was Victor I, bishop of Rome (189-198), who threatened to break off communion with the “Fourteeners.”

Fortunately that did not happen, but the future lay with Pope Victor and his allies. The feast of the resurrection would be determined by the major churches, especially Rome in the Latin-speaking parts of the ancient world.

In the Bible, every major feast had a time of preparation. Since feasts included much food as part of the celebration, the Christians thought that a fast before the Easter feast would be appropriate for all people except the ill and small children.

The first such fast was three days, corresponding to the days from the crucifixion to the resurrection.

In 325, the first ecumenical council met at Nicaea. Since all the bishops of the Roman Empire were there, they discussed major matters including the pre-Easter fast.

[hotblock2]

Candidates for baptism fasted for 40 days just as Jesus did after his baptism, and the bishops at Nicaea decreed that all Christians should fast for 40 days before Easter, effectively creating the season of Lent.

Yet there was more. Lent stretched to 40 days, but the final days before Easter were significant, especially since the Gospels give accounts of Jesus’ last parables and work among the people then.

But there was more — in the last days of his life, Jesus had his last supper with his closest disciples, and this became a model for many liturgies since it involved bread and wine.

All this took place in Jerusalem, and, appropriately, it was the Jerusalem church that began to specify the different days and events of this last week, effectively crafting what we now call Holy Week.

This practice would expand so that virtually every day of that week had something special about it. The Jerusalem approach to the last week of Lent would spread widely.

Both Easter and Holy Week would change over the centuries and in the endless number of places to which Christianity would expand, but both are key elements of the liturgy, a Greek word that means “the work of the people.”

By recognizing the great status of Holy Week and Easter, the ancient church made it clear how important the liturgy, “the work of the people,” is for us all.

The one thing all believers do in common is to worship, and the ancient bishops had created a new and meaningful time for worship.

***

Joseph F. Kelly is retired professor at John Carroll University in University Heights, Ohio.

PREVIOUS: The resurrection through Mary’s eyes

NEXT: Being Easter people informs how parish prays and acts

Share this story