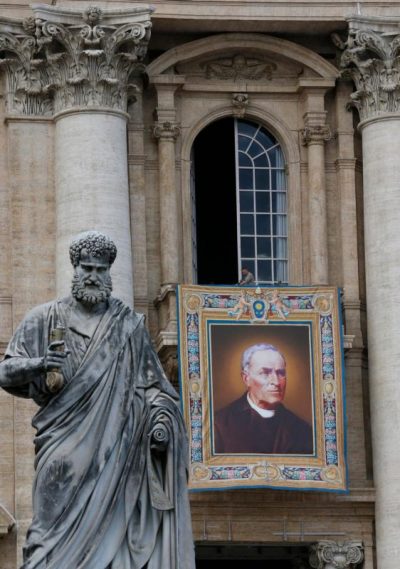

A worker prepares a banner of Italian Father Vincenzo Grossi, founder of the Institute of the Daughters of the Oratory, on the facade of St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican Oct. 16, 2015, two days before Pope Francis made him a saint. Over the course of 2,000 years, the church has canonized myriad bishops, priests and deacons, and what is common to all of them is their path to holiness was marked by a unique sacrament: holy orders. (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

Over the course of 2,000 years, the church has canonized myriad bishops, priests and deacons. Certainly each of these men lived an exemplary life of holiness, but what is common to all of them is their path to holiness was marked by a unique sacrament: holy orders.

The term “order” (“ordo” in Latin) refers to a group or a body into which a man is incorporated through the rite of “ordination” (“ordinatio”).

Through the reception of the church’s rite of ordination, a man is consecrated, or set apart, by the laying on of hands and prayer of consecration, and is incorporated into the order of bishops, priests or deacons into which he is ordained.

The rite of ordination bestows on the new bishop, priest or deacon a special gift of the Holy Spirit, which enables him to exercise a “sacred power” for the service, upbuilding and communion of the church.

The sacrament of holy orders is the concrete way “through which the mission entrusted by Christ to his apostles continues to be exercised in the church until the end of time” for the salvation of all (Catechism of the Catholic Church, No. 1536).

Although the sacrament of holy orders is constituted as one sacrament, there are three different “degrees” in the sacrament: the episcopate (bishops), the presbyterate (priests) and the diaconate (deacons). All are at the service of communion in the church, but each in its own unique way.

Bishops hold the chief place in the exercise of service to the church. For this reason, bishops receive the fullness of the sacrament as they take the place of Christ as teacher, shepherd and priest, and represent him “in an eminent and visible manner” (No. 1558).

[hotblock]

Bishops are united with one another under the pope, and in that communion they form a “college” with personal responsibility for both their individual dioceses, as well as for the entire universal church.

Priests are, to a subordinate degree, co-workers with the bishops. Through ordination they are configured to the person of Christ and are consecrated to preach the Gospel, to represent Jesus to the church and to lead those entrusted to their pastoral care in divine worship. In the celebration of Mass, priests exercise this ministry to a supreme degree.

Deacons constitute the last degree in the sacrament of holy orders. Although not a priestly degree, deacons are consecrated to serve, and they hold a special role in the assistance of the bishop and priests at Mass. Deacons are configured to Jesus “who came not to be served, but to serve” (Mt 20:28).

In a society with tendencies toward radical individualism, many question whether we need the church in general, and a church hierarchy in particular; is the church absolutely necessary for salvation?

Hopefully as Catholics we understand the answer is an unequivocal “yes” to all the above. For others, however, that answer is not as clear, and they have legitimate questions on the topic. The journey toward “yes” often requires an honest, conscientious consideration of key philosophical notions such as “freedom” and “authority.”

Much has been written already on that last point, but beyond the search for one’s philosophical presuppositions and the subsequent need for their purification, it is beneficial to ask oneself another question not considered frequently enough: What does God want?

We can find an initial answer to this last question by turning to the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

The catechism offers a pithy historical overview of the sacrament of holy orders in Scripture and the living prayers of the church. Scripture reveals that the Israelite people were established by God as “a kingdom of priests, a holy nation” (Ex 19:6), and that God chose and set apart the tribe of Levi, one of the 12 tribes of Israel, for divine worship and liturgical service (No. 1539).

The church sees a prefiguration of the ordained ministry of bishops, priests and deacons of the New Covenant already in the Old Covenant priesthood of Aaron, the institution of the 70 elders and the liturgical service of Levites responsible for proclaiming the word of God and offering sacrifices and prayer (No. 1540-41).

[hotblock2]

While the sacrifices of the Old Testament did not have the power to restore communion between God and humankind, everything the priesthood of the Old Testament foreshadowed does ultimately find its fulfillment in the priesthood of Jesus Christ, “the one mediator between God and men” (1 Tm 2:5), when he offered the perfect sacrifice of himself on the cross for the salvation of the world (No. 1544).

It is precisely so that this one, perfect, eternal and saving sacrifice would be made available to all people throughout history that Jesus constituted his apostles as priests of the new covenant and gave them authority to celebrate the eucharistic sacrifice. Jesus established the hierarchical nature of his church so that he could always be present to his bride, the church.

Jesus’ words at the Last Supper to his apostles to “do this in memory of me” reveal his plan to bring about true communion with God and others in the Eucharist and supremely fulfill his promise that “I am with you always, even until the end of the age” (Mt 28:20).

***

Father Anderson is a priest for the Society of Our Lady of the Most Holy Trinity. He holds a licentiate of sacred theology in dogmatic theology and has served as director of the office of catechesis of the Diocese of Paterson, New Jersey. He is pastor of St. Mary’s Parish in Dover.

PREVIOUS: Lenten preparation and penance lead to a life of joy

NEXT: From baptism to burial, the priest’s ministry is not his own

Share this story