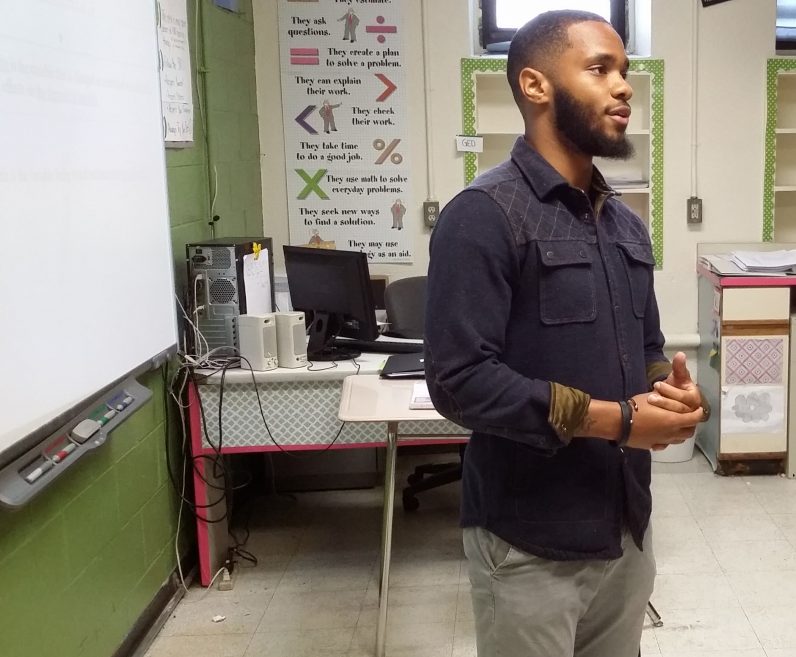

Quamiir Trice, a former student at St. Gabriel’s Hall for at-risk youth, returned to the school in June 2018 to teach mathematics. Now a Philadelphia-based educator, Trice inspires his students by drawing on his experiences at the school, an outreach of archdiocesan Catholic Social Services. (Photo by Gina Christian)

When he arrived at St. Gabriel’s Hall in Audubon nine years ago, Quamiir Trice was in handcuffs.

Arrested for dealing crack, the 15-year-old had been sent to a residential treatment program for at-risk youth offered by St. Gabriel’s, part of archdiocesan Catholic Social Services (CSS).

On June 27, Trice returned to St. Gabriel’s – this time, as a Pennsylvania state certified educator, fresh from his fourth-grade classroom and ready to teach mathematics at summer school.

[hotblock]

“They took the handcuffs off as soon as my feet hit the ground here,” Trice said, recalling his first moments at St. Gabriel’s as a troubled teenager. “Everything here was so green and beautiful and peaceful. It definitely made me feel like I was in a good place.”

During his time at the Middle States accredited school, Trice earned his GED while displaying a gift for mathematics. Through intensive counseling sessions, he learned to manage his emotions and to make more constructive life choices. And he discovered that the variables in his life added up to something new: hope through faith in God.

“I became spiritually grounded when I came to St. Gabe’s,” Trice said. “That was vital.”

Wounded human beings, not damaged goods

“We can’t preach or proselytize a specific faith because we’re publicly funded,” said John Mulroney, principal of St. Gabriel’s. “But we’re allowed to let the students explore their own faith traditions, and we seize every opportunity to help them do just that.”

Mulroney said that Trice, who had been raised as a Christian, embraced the 12-step program directive to “let go and let God” often heard in the school’s drug and alcohol rehabilitation unit, where he recovered from addiction. In doing so, Trice had to confront his pent-up rage, frustration and grief – the legacy of life on the street, where drugs and guns claim a disproportionate number of minority youth.

“I actually remember my best friend getting killed while I was here,” he said. “My social worker called me to his office that day; we had a great relationship and he knew that something was off about me. And of course there was. My best friend was dead.”

[tower]

Trice said that having a safe space in which to process his harrowing experiences – which included an unstable home life, substance abuse, truancy, drug dealing and lost relationships — was “pivotal.”

Mulroney cites the school’s trauma-informed care treatment as the key to reaching its students. By addressing the core reasons why youth engage in at-risk behavior, staff can foster communication skills, emotional intelligence, non-violence and a sense of social responsibility among students.

“These kids are wounded human beings, not damaged goods,” said Mulroney. “There’s a difference, and our first step is making these young men feel safe and cared for in this environment,” he said.

Once students are assured of their protection, they can work through their anger and sorrow, often through what Mulroney describes as “cleansing tears” that unclench both fists and hearts. During the grieving process, students participate in multiple therapy groups, meeting even on weekends to share their stories and to support each other’s growth.

Learning to teach

As they come to terms with their losses, students can then begin to focus on the future, developing the talents and skills buried under their scars. Mulroney noted that Trice’s mathematical aptitude, masked by a straight-F report card at his former high school, emerged at St. Gabriel’s.

“He was our top GED math student when he was here,” Mulroney said, adding that Trice quickly rose to the head of his class, graduating as salutatorian in 2011 and then enrolling in Community College of Philadelphia.

After obtaining his associate’s degree, Trice completed his undergraduate studies at Howard University, majoring in elementary education. His leadership roles in several education initiatives have led Mulroney to tease Trice for “hobnobbing with presidents.”

[hotblock2]

“He’s met President Obama several times, along with the president of the MacArthur Foundation,” said Mulroney. “Actually, in one photograph, it looked like he had Obama’s ear, rather than the other way around.”

Because of his academic credentials and a need for greater diversity in educational staffing, Trice was heavily recruited by several school districts and graduate schools throughout the country. He chose to return to his hometown, accepting a position as a fourth-grade instructor at Bethune Elementary School in North Philadelphia.

Returning to serve

As he was wrapping up the school year, Trice approached Mulroney about returning to teach at St. Gabriel’s during the summer.

“We have a quote all through St. Gabe’s that says ‘enter to learn, leave to serve,’” Trice said. “Coming back here is a dream come true.”

In a sense, Trice had never completely left St. Gabriel’s, which reintegrates its graduates through an aftercare program. A CSS counselor, assigned by the city’s family court, follows up regularly with former students for approximately six months after they leave St. Gabriel’s to ensure their progress.

Trice needed that safety net when he hit a rough spot after his St. Gabriel’s graduation and got kicked out of his grandparent’s house. Distraught, he called a former dean at the school for guidance.

“I knew my goal was to still stay on track and stay focused, but I needed help,” Trice said. “He listened and encouraged me, and he said, ‘You have our support.’ And just knowing that really made me feel a lot more confident moving forward.”

Quamiir Trice (left) and student Sherman Jones discuss algebra equations during a June 2018 class at St. Gabriel’s Hall, a residential treatment program for at-risk youth located in Audubon. Now a Philadelphia-based educator, Trice is a graduate of the school, an outreach of archdiocesan Catholic Social Services. (Photo by Gina Christian)

As a new teacher, Trice continued to consult his mentors at St. Gabriel’s for advice on classroom management and teaching strategies.

Trice is passionate about cultivating math skills in his students, especially since urban youth are underrepresented in scientific disciplines. He relishes the clarity of mathematics, which hones students’ analytical skills while building confidence, and he weaves life lessons into his lectures.

“I tell my students that whenever you have a variable in an equation that you’re solving for, that is your goal,” Trice explained. “You focus on that goal, and all of the other numbers, all those distractions, don’t really matter.”

For Trice, who plans to attend law school and to develop educational policy, faith in God is the ultimate variable.

“I came to the conclusion that I don’t teach for my students any more – I teach for God,” said. “I don’t feel like I’m doing any of this on my own. It feels like a movie script, and God is writing this story to give himself the glory.”

Watch a video on Quamiir Trice’s return to St. Gabriel’s Hall:

PREVIOUS: Nun-physician has spent much of her life educating young people about NFP

NEXT: Judge sees no religious bias against Catholic agency on same-sex foster care

Share this story