Marilyn Miranda, 9, draped in a Salvadoran flag, attends an immigration rally with her mother outside the U.S. Capitol in Washington June 4, 2019. With global population movements at a historical record, immigration will remain a key pastoral concern for the Philadelphia archdiocese and its new shepherd, Archbishop Nelson Perez. (CNS photo/Leah Millis, Reuters)

Archbishop Nelson J. Perez has been entrusted with a flock that extends well beyond the five-county archdiocesan area, one that in a sense calls the entire world its home.

That’s because immigrants make up almost 15% of the city’s population, and 10% of its suburban headcount.

And with numbers already surpassing some projections for the year 2050, immigration will remain a key pastoral concern in the Archdiocese of Philadelphia for years to come.

[hotblock]

As the son of Cuban immigrants, Archbishop Perez – who reportedly once described himself to Pope Francis as “made in Cuba, packaged in Miami” – knows the migrant experience in all its complexity and challenges.

That awareness will serve him well as he leads area faithful in welcoming the stranger and forming a diverse yet unified body of Christ, even amid resistance from some fellow believers.

‘Who in their right mind leaves their homeland?’

At a January 2020 meeting of the area’s Catholic Coalition for Migrants and Refugees, keynote speaker and Sister of St. Joseph Carol Zinn asked a candid question: “Who in their right mind leaves their homeland?”

She had a ready answer, having spent 13 years working at the United Nations.

Despite the issue’s political volatility, said Sister Carol, migration should be viewed for what it historically has been: the normal and necessary movement of peoples, an occurrence that on balance has had more positive than negative effects.

At the same time, she said, external forces such as armed conflict, drug trafficking, violence, poverty and natural disasters have increasingly driven individuals and families to seek a better life elsewhere.

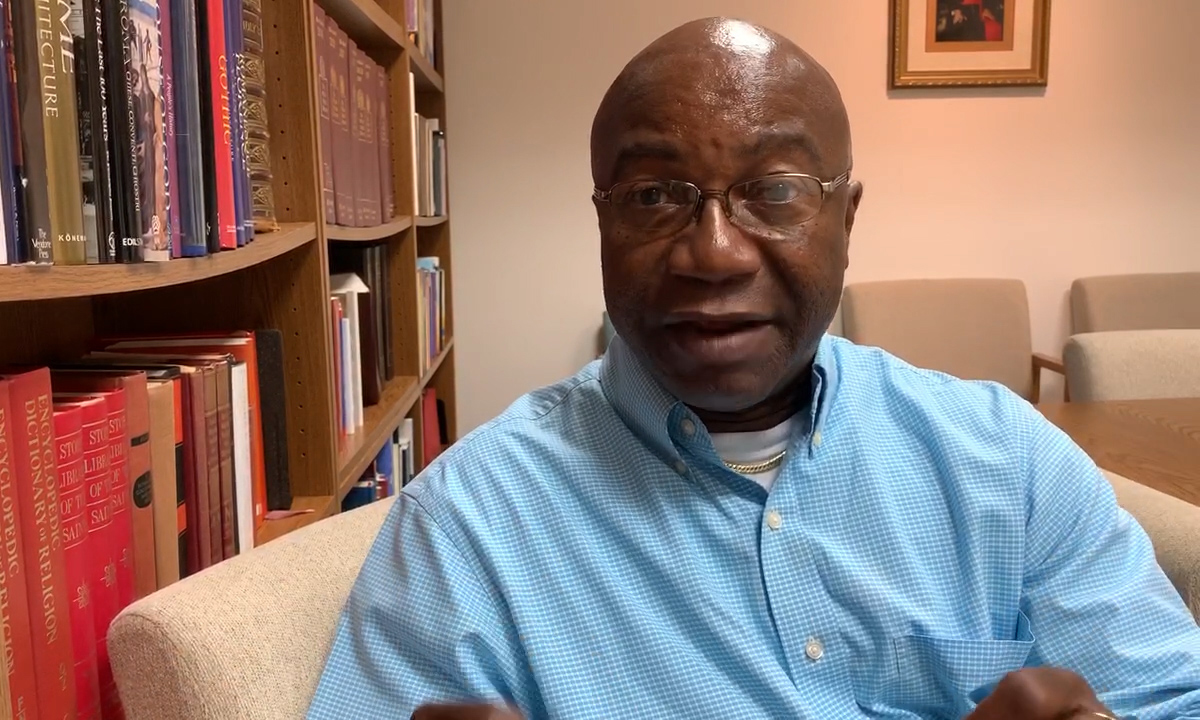

Samuel Z. Abu, who sought U.S. asylum after fleeing civil war in his native Liberia, draws on his personal experiences in his work with archdiocesan Catholic Social Services’ refugee resettlement program. (Photo by Gina Christian)

For Samuel Abu, two brutal civil wars that ultimately killed an estimated 200,000 to 250,000 drove him from his native Liberia some two decades ago. Having obtained asylum in the United States, Abu now helps to lead the region’s Liberian Catholic community, while working full time as a parish and volunteer coordinator for the Refugee Resettlement Program of archdiocesan Catholic Social Services (CSS).

“I know what it means to go to a country where you know no one, and you depend only on God, praying that he will touch the heart of someone to help you,” said Abu.

To date, CSS’s resettlement program has assisted 84 refugees vetted by the federal government, arranging for housing, employment, schooling and bank accounts. Abu said that over the last two years, about 40% have applied for or received permanent residency.

‘Insanely difficult to become a U.S. citizen’

However, “it’s getting insanely difficult” to become a U.S. citizen, according to Philadelphia-based immigration attorney Christopher Casazza, who represents a number of clients from archdiocesan parishes.

Under the Trump administration, immigration – both legal and illegal – has been severely curtailed, even as global population movements are at their highest since World War II.

[hotblock2]

The UN estimates that there are currently an estimated 272 million migrants, almost 26 million of whom are refugees, with 41.3 million internally displaced in the countries of origin.

Yet for fiscal year 2020, U.S. refugee admissions have been slashed to historic lows – just 18,000.

Travel bans and visa restrictions have been expanded; applications for residency and asylum can languish in immigration courts for years.

Due to a new “public charge” rule, any reliance on government assistance for food, housing and medical care can threaten immigration applications, effectively creating a wealth requirement for citizenship, according to several analysts.

Vincentian Father Kurniawan Diputra counsels a longtime St. Thomas Aquinas parishioner who, along with her husband, are facing deportation to their native Indonesia, which they fled some 20 years ago to escape ethnic and religious persecution, Jan. 16. (Photo by Gina Christian)

“Many people have applied for asylum, tried to build their lives, have steady jobs here, but their dreams never come true,” said Vincentian Father Kurniawan Diputra, chaplain of the archdiocese’s Indonesian Catholic community.

At St. Thomas Aquinas Parish in South Philadelphia, Father Diputra has counseled two Indonesian couples who, after fleeing religious and ethnic persecution, were imprisoned by Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) after years of trying to seek U.S. citizenship.

“The ICE detentions show us that (immigration authorities) are pointing to Philadelphia because we are a sanctuary city,” said Sister Gertrude Borres, director of the archdiocese’s Office for Pastoral Care of Migrants and Refugees (PCMR), and a member of the Religious of the Assumption. The PCMR office provides Mass and sacraments in some 17 languages, along with information and guidance for its client communities.

So far, Philadelphia is not among the nine sanctuary cities where ICE agents will be supplemented by elite Customs and Border Protection officers with sniper certification, who according to the New York Times will assist in routine immigration arrests over the next four months.

Given the endemic poverty, violence and corruption in several nations, many migrants – particularly from Central and South American nations — are nonetheless willing to risk such arrests, if they can make it to U.S. soil in the first place.

A border wall, a “Remain in Mexico” policy (officially known as the Migrant Protection Protocols) and hardline agreements with Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala have created a humanitarian crisis for an estimated 60,000 asylum seekers now encamped in some of Mexico’s most dangerous cities.

A nightmare for ‘Dreamers’

Children and youth routinely find themselves in the crosshairs of the immigration crisis. Based on census data, the American Immigration Council estimates that more than four million U.S. citizen children under 18 live with at least one undocumented parent.

For them, fear and uncertainty are a way of life, despite their citizenship.

“One woman asked me, ‘What are my children going to do if they come home from school and find that my husband and I have been deported?’” said IHM Sister Rose Patrice Kuhn, director of Hispanic pastoral ministry at St. William Parish in Philadelphia.

Those brought to and raised in the U.S. by undocumented parents are at risk for deportation to countries of origin whose language and culture are virtually unknown to them. Since 2012, almost 800,000 so-called “Dreamers” had been protected by the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which the Trump administration rescinded in 2017. Following several court challenges, the fate of DACA is now in the hands of the Supreme Court, which is expected to issue its decision by June of this year.

Accompanying migrants at every step

Despite such headwinds, many in the archdiocese remain committed to welcoming immigrants and to addressing both their material, legal and spiritual needs.

“All that is being asked of any of us is to love our brothers and sisters,” said Amy Stoner, director of CSS’s community-based and homeless services. “This is what it means to be the church.”

Attorney Catherine Baggiano has helped more than 350 individuals attain U.S. citizenship in her work with archdiocesan Catholic Social Services. (Photo courtesy of Catherine Baggiano)

In addition to its resettlement program, CSS provides immigration legal services, working with partners such as the Catholic Legal Immigration Network (CLINIC), the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), the city of Philadelphia and the Mexican consulate. Attorney Catherine Baggiano, who directs the CSS legal effort, said that her office has met with at least 2,500 clients and has opened more than 1,750 cases over the past five years.

Two years ago, various outreaches sponsored by the archdiocese, parishes, colleges and religious orders formed the abovementioned Catholic Coalition for Migrants and Refugees, pooling their resources and information to better serve area immigrants. Sister of St. Joseph Eileen McNally, the coalition’s co-chair, said that as part of the effort her order is securing additional housing for migrants.

In July 2019, following a sharp increase in ICE detentions, the coalition also launched a “ministry of accompaniment” through which volunteers attend immigration hearings, detention center visits and other appointments with migrants.

According to Abu, one Honduran mother told a group of such volunteers that their presence at her 13-year-old son’s hearing helped prevent the child’s deportation.

Justin Sharaf, a member of the Pakistani Catholic community in Philadelphia, lights a votive candle at an April 21, 2018 prayer vigil held at St. William Parish for persecuted Christians in Pakistan. (Photo by Gina Christian)

CSS’s family service centers, located throughout the five-county Philadelphia area, provide an array of supports for immigrants, from basic necessities to tools for overall “cultural integration,” said Camille Crane, administrator of CSS’s Casa del Carmen site in North Philadelphia.

Crane said that she and her colleagues ensure that clients “feel safe and cared for,” and “celebrate each milestone” of their progress.

But real change for immigrants must begin in the hearts of the faithful, said Justin Sharaf, a lay leader within Philadelphia’s Pakistani Catholic community.

Sharaf, who highlighted the ongoing persecution of Christians in his native Pakistan, said that border walls can and do exist even within the pews.

Sociologists have identified a recent wave of “Christian nationalism” that frequently uses religious beliefs to defend anti-immigrant policies.

The only way to prevent “today’s mistakes from becoming pronounced in the future,” said Sharaf, is to “integrate ethnic minorities, and create a larger Catholic family.”

PREVIOUS: Philly’s Latino, Hispanic Catholics welcome one of their own as shepherd

NEXT: Welcome home, Padre Nelson

Share this story