(Nathan Costa/Unsplash. Stock image for representational purposes only.)

As gun violence continues to plague the Philadelphia region and the nation as a whole, two teens served by archdiocesan Catholic Social Services (CSS) are providing an inside view behind the bullets.

The youth, who were adjudicated by Philadelphia’s juvenile court system to CSS for treatment, agreed to speak with CatholicPhilly.com about their own experiences with gun violence and its tangle of risk factors.

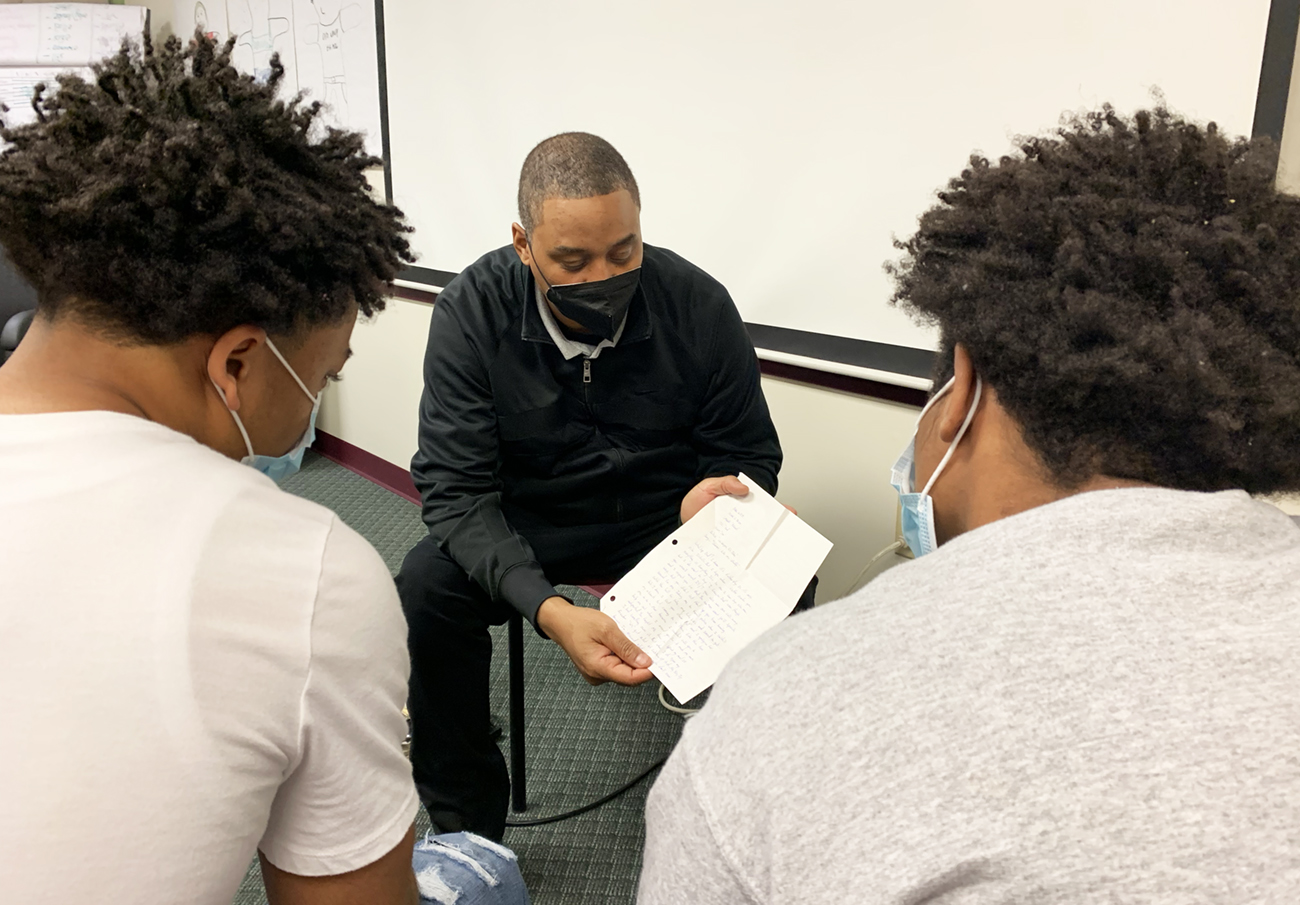

The 90-minute interview, recorded earlier this year and edited as a CatholicPhilly.com podcast, was conducted under the supervision of CSS youth care worker Gary Hill, whose own son had survived a shooting attack several years earlier.

Hill and the youth – who asked to be identified as L.A. and Omar, and whose quotes have been preserved in their original Black English – agreed that gun violence in the city has dramatically escalated over the years, with more bystanders becoming victims, and fewer witnesses willing to cooperate in law enforcement investigations.

Having grown up amid guns, neither L.A. nor Omar were confident the solutions typically advanced to address the issue – such as legislation, enhanced policing and community outreach – will produce any immediate or lasting effects.

(In their own words: Listen to CatholicPhilly.com’s podcast interview with Omar and L.A. on gun violence.)

That’s because at both ends of the barrel, they said, are complex, interconnected factors spanning individual, family and community levels – and all of those concerns converge at the tip of the bullet.

‘Kill or be killed,’ and the rules of chaos

On one hand, the chaos of gun violence in Philadelphia is partly shaped by some unwritten but very real “rules” that seek to preserve territory and privacy, said Omar and L.A.

“I don’t know why cops think we just killing for no reason,” Omar said. “The world’s different now. It’s kill or be killed.”

Avoiding either fate requires a keen awareness of one’s surroundings and a deference to those perceived to hold power over them.

Catholic Social Services (CSS) youth care worker Gary Hill, who almost lost his own son to gun violence, speaks with “Omar” and “L.A.” (not their real names), two Philadelphia teens adjudicated to CSS for treatment. (Gina Christian)

“Mind your business. Keep your head up, keep your feet moving,” said L.A. “If you not from there, don’t be staring. You don’t know what’s around that corner, so if you trying to be nosy and see what (someone is) doing, you turn around that corner and get your head knocked right off your shoulder.”

Heavily tinted car windows (often darkened well in excess of Pennsylvania’s approved levels) can – along with vehicle speed — be both a defense and a provocation, the youth said.

“You driving too slow and … you in a tinted car, you don’t know if they going to drop the window or not,” said Omar. “So shoot first.”

Pressure to “be down with gangs” and impress fellow members is also behind the surge in killings, he said.

Witnesses to shootings and related illegal activities on Philadelphia’s streets are silenced by the fear of “consequences and repercussions,” said Omar.

[tower]

“They really live by that code (of) not ratting,” L.A. agreed. “Witnesses are scared. Let’s say an old lady see me shooting. She not gonna come to the court room; she live on my block. She see what I be doing all day, every day. She not coming to that court hearing. … Her grandbabies be over there; you feel me?”

On the street, revenge is forever, both teens said.

“People don’t let stuff go,” said L.A. “I’m not going to forget you shot me. … I’m going to remember your face. … If I see you again, you’re gonna die.”

‘Bullets got no names’

But for all the so-called rules, in the end, “bullets got no names,” said Omar. “(If) you shot at, (then) you shot at.”

“They don’t be having no aim,” L.A. said. “They just shooting. … So don’t think they going to have mercy ‘cause you with your mom or you with a little kid or something. … People don’t care about that no more.”

Bystanders, including babies, are “getting killed (who) got nothing to do” with the grievances – known as “beefs” – that lead to pulled triggers, he said.

Such conflicts can start small and flare for “a whole lot of different reasons,” quickly drawing in “crews” that line up to do battle across the city’s neighborhoods, said L.A.

“You shoot one of us … we shooting at you, and people (are) dying,” he said.

Fueling the fury

Social media, rap music, video games, drugs and alcohol all fuel the fury, said Hill and the youth.

“Music is supposed to touch their soul, but it’s controlling their minds at this point,” Hill said. “The rap tells you, ‘Catch him coming out the store, hit his door.’ … The lyrics (say) it’s hip to kill you at the mall, it’s hip to kill you coming out your house. … It’s glorification.”

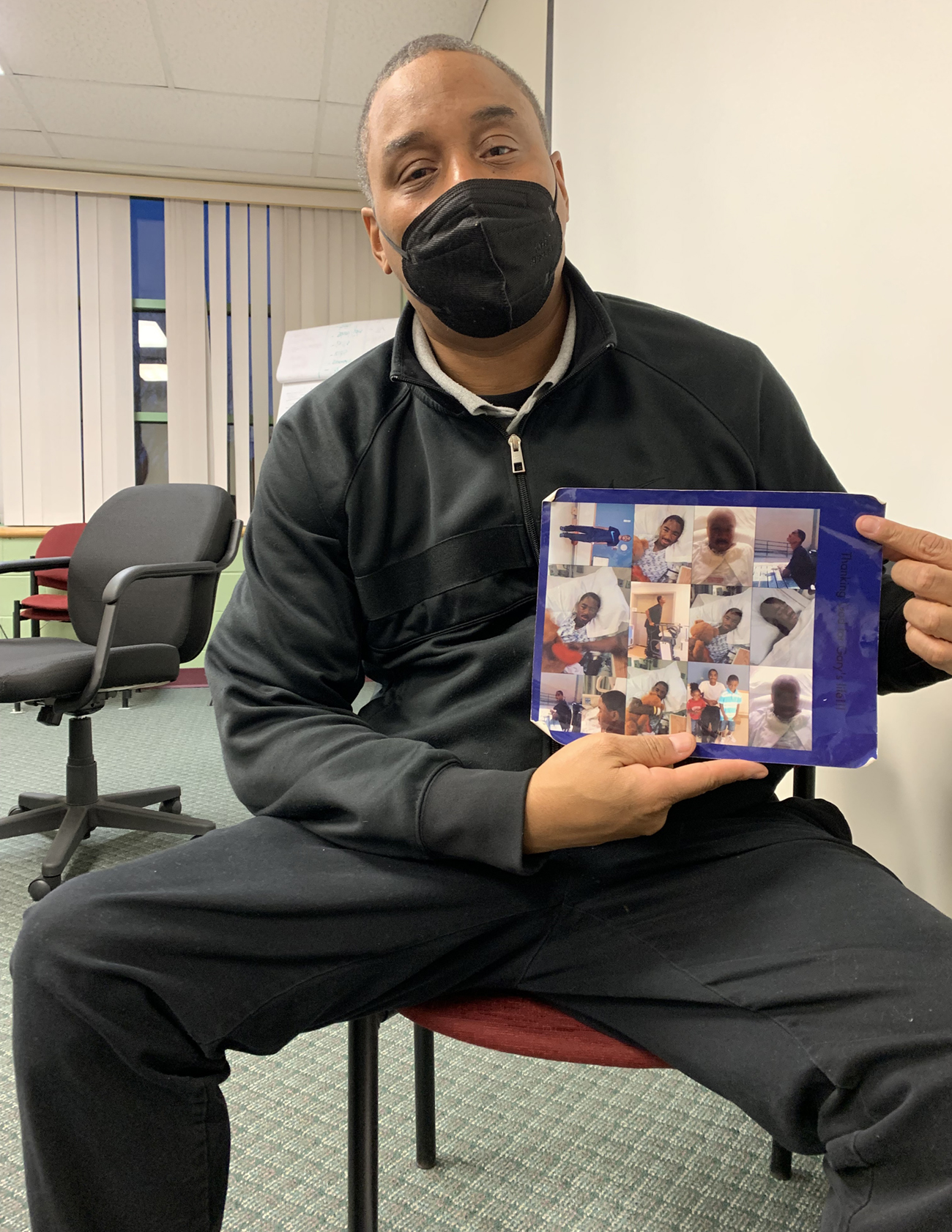

Gary Hill, a youth care worker with archdiocesan Catholic Social Services, displays pictures of his adult son, who survived a near-fatal shooting attack while a youth. (Gina Christian)

Rappers “be saying stuff we been through; that’s why we like (their music),” said Omar, while L.A. noted the lyrics “start getting in your head, (and) you start living that song.”

Against that soundtrack, Instagram and other social media platforms allow youth to project a fantasy image of themselves, stirring up rivalries and tempers.

Those who post pictures of themselves flaunting “nice designer stuff … money (and) jewels,” often pawned and bartered just for show, put themselves at risk of being robbed and killed, said L.A. and Omar.

In addition, drugs, alcohol and video games mask – and mar – reality, they said.

“I got friends (who) really do think it’s like a video game,” said L.A. “And you would never see them sober, ever. They can’t stand being sober; they got to be high because they done so much stuff and been through so much stuff.”

‘People got trauma’

At the core of the city’s gun violence, said the youth, are wounds inherited and intensified with each new generation: scars inflicted by broken families, addiction, racism, poverty and unrelenting experiences of everyday violence.

“People got trauma,” said L.A. “They don’t just be trying to be tough or nothing. … I’ve seen people close to me get shot right in front of my face, (with) they blood on me. That mess with your head. … I used to think it was normal ‘cause it’s all I was used to.”

With little hope for change, youth despair and conclude that “nobody got it good in Philly,” said Omar.

Parents and children alike are too often swept into a downward spiral, they said.

[hotblock]

“I didn’t have my folks (in my life),” said L.A. “My pop is doing 22 years in jail. My mom was on drugs; both my grandmoms was on drugs.”

As a very young child, L.A. even “slept on the streets” with his mother; when he turned eight, “friends started dying,” he said.

The streets offer little protection, and even less opportunity for escape, said the teens.

Neighborhood businesses are reluctant to hire local youth, fearful their presence will make stores targets of gun violence, they said.

Asked if there were any places in which they felt safe, the teens shook their heads.

“Nowhere,” said L.A. “Or being locked up.”

Asked if they had any dreams, the teens shook their heads again.

“Where I come from, we don’t even think like that,” said L.A. “We hope we make it till tomorrow.”

No easy solutions, but clues in the cries

The teens were adamant that while ending gun violence was an essentially impossible task – “it’s not gonna happen,” said Omar – curative responses to the crisis should not come from “outsiders.”

“They don’t even live here, and they telling us what should be done,” Omar said.

Many proposals are simply naïve and unrealistic, especially as gun violence increasingly breaks out in more neighborhoods at all hours of the day and night, added L.A.

“People thinking they just gonna make boys and girls clubs, and get the YMCAs popping – that’s not working,” he said.

He pointed to the March 2021 murder of 21-year-old Dominic Billa, stepson of a Philadelphia County detective in the District Attorney’s office, who was shot while eating dinner in the food court at Philadelphia Mills Mall. Gregory Smith, then 21, was charged in the killing, which took place after a fight among the tables.

“If you could die in a mall, what makes you think you can’t die in that boys and girls club in the ‘hood?” asked L.A. “What makes you think I’m going to stop my mission to kill you because you in the boys and girls club playing basketball? That don’t matter to me.”

But while gun violence seems inexorable, both teens said they and their peers ultimately know firearms can’t fill their deepest needs – and those cries of the heart provide clues as to what actually might help stop the bullets.

“I wish I had my dad in my life,” said L.A.

“I want to be happy with my family, ‘cause my mom died and I got nobody; I’m just here,” said Omar. “I just want to know what my life would be like if my mom was still here. That’s all I want to know.”

PREVIOUS: Report: $78 million paid to victims of clergy sex abuse in archdiocese

NEXT: Catholic school student winds up to throw first pitch at Phillies game

Share this story