In October 1958, Philadelphia’s Msgr. John Miller was a young seminarian with just two years of philosophy behind him when he was sent to Rome to finish his philosophy, theology and probably graduate studies at the Pontifical Roman Seminary at the Lateran, which is attached to the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran. He stayed eight years.

Contrary to popular assumption, St. John Lateran, not St. Peter’s Basilica, is the cathedral of Rome and the cathedral of the pope.

It was the day after he arrived, Oct. 9, that all the bells of Rome started to toll. Eugenio Pacelli, Pope Pius XII, had died at Castel Gandolfo, after a reign of 19 years. Cardinals from around the world hurried to Rome for the pope’s funeral and the conclave that would elect his successor.

[hotblock]

Among the early arrivals was elderly Cardinal Angelo Roncalli, Patriarch of Venice, who was himself a graduate of the Lateran Seminary and chose to stay there during the period before the cardinals were sequestered in the Vatican for the conclave.

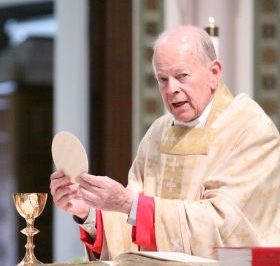

Msgr. Miller, who today is parochial administrator of St. Michael Parish in North Philadelphia, did not meet Cardinal Roncalli during this brief stay, and really knew nothing about him.

The conclave itself opened on Oct. 25 and the new pope was elected on Oct. 28 on the 11th ballot.

The throng in St. Peter’s Square saw the white smoke arise from the Sistine Chapel and knew the election was over.

Without knowing whose name would be announced, Msgr. Miller remembers commenting to a friend, “I hope he takes John for his name,” and it wasn’t because it was his own Christian name.

Historically John had been the most popular papal name either by birth or chosen by popes upon their election. There were 23 to be exact.

But the last man to bear the name was John XXIII (1410-15) at a time of schism when there were no less than three men declared pope by different factions within the College of Cardinals. All three were forced to resign, and two, including John, were considered antipopes on most lists.

The name John was never chosen again for five and a half centuries. Msgr. Miller knew this from his high school religious history classes at St. James High School in Chester.

Cardinal Roncalli settled the matter when he chose the name John and insisted it should be John XXIII. As he would explain on different occasions, his patron saints would be John the Baptist and John the Evangelist.

It was just a few days later that Pope John returned to visit St. John Lateran and the seminarians had the thrill to be individually introduced to him.

There would be other meetings too. The next year, on Jan. 25, the Feast of the Conversion of St. Paul, all the seminarians were bused to St. Paul’s Outside the Walls, where the great apostle is entombed, and where Pope John would celebrate the liturgy. There would be an important announcement, it was rumored.

There certainly was. It was at this liturgy Pope John announced he would call a synod of bishops and also an ecumenical council to address the challenges of modern society.

“That’s nice,” Msgr. Miller remembers thinking. He did not realize at the time how very important ecumenical councils can be and this, Vatican Council II, would be among the most ground-breaking events in the 2,000-year history of the Church.

An up close and personal moment with Pope John came in 1962. That year the pope decreed that all cardinals must be bishops; prior to that the lowest rank, the cardinal deacons who filled various offices at the Vatican, were priests not bishops.

On Holy Thursday Pope John went to St. John Lateran to consecrate the cardinal deacons as bishops. Whenever there were liturgical events at St. John’s the seminarians were pressed into service for the minor parts of the ceremony.

Because they spoke English, John Miller and another seminarian were told to assist the Irish Cardinal, Michael Browne, during the ceremony. But when the Dominican Cardinal Browne arrived he was accompanied by two young Dominicans, so the two seminarians assumed their services were not needed and started to return to the seminary.

On the way, Msgr. Enrico Dante, the papal master of ceremonies, saw them and called, “We need you at once, subito, get over here.”

It seems there was a major mix up; the men who were supposed to assist Pope John XXIII were not there. Msgr. Dante ordered them to help the pope don his vestments for the ceremony, which they did. The final bit of vesture was jeweled pins to keep the vestments in place.

John Miller was just ready to stick one of the pins in the garment, when the pope, possibly from previous experience, warily said, “Give it to me, I’ll do it myself.”

With the task completed, the two young seminarians once more were getting ready to leave when they saw Cardinal Browne all by himself in the procession. Apparently the two Dominicans were not his assistants. They hastily went over and joined him in the procession. “It was a comedy of errors,” Msgr. Miller recalls.

As time went on, Pope John was clearly failing in health. In 1963, when he made the first papal visit to the President of Italy, Msgr. Miller recalls seeing the ceremony on television. Protocol dictates one stand when addressing a head of state. “I hope you will indulge an old man who sits down,” Pope John said.

“The cancer that killed him was advancing,” Msgr. Miller said. In late spring there was a death watch.

“I was thoroughly disgusted with everything,” Msgr. Miller recalls. “We adored him, he was so lovable, and in the media nobody cared, all they would talk about was who his successor would be. It would be Cardinal Montini (Pope Paul VI). I hated him at that time but I knew it wasn’t his fault. I really do have a great deal of respect for him.”

Pope John died June 30, 1963, and considering how much he was revered in his day, especially because of the changes he brought to the Church, it is perhaps surprising how little this generation remembers him.

“There was the same enthusiasm for him then as there is for Pope Francis today,” Msgr. Miller said.

PREVIOUS: For Blessed John XXIII, calling Vatican II was an act of faith

NEXT: Days in the life of Pope John XXIII

Kudos to Mr. Baldwin for so precise and witty a transcription of my remarks, but this has always been a hallmark of his reporting. Thanks very much, Lou.