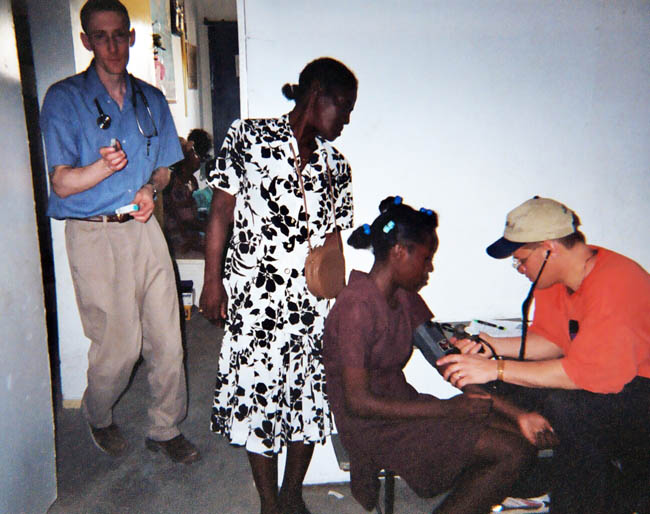

Father Terry Weik (left), parochial vicar at Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish in Doylestown, poses with Pascal Voltaire outside the medical clinic at St. Jude Parish in Port-au-Prince. The priest and about 50 Our Lady of Mount Carmel parishioners are sponsoring Voltaire’s education at Caribe University in Port-au-Prince, which he began last October.

Bringing suitcases full of medicine and vitamins, initially filling its church auditorium before departure, Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish in Doylestown sends nurses and doctors on mission trips at least once a year to Delmas, a section of Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

On the last day during one recent trip, Haitians desperate for health care tossed living babies over the church wall of St. Jude Parish, the mission’s base in the Haitian capital. In the native Creole tongue, Tom Kardish, the mission’s founder, tried to calm the chaos and shouted to the people, “If you calm down, we’ll come back. If you leave nicely, we’ll come back.”

A boney-fingered man pointed at him firmly. “What date?” he asked.

In Haiti, over-the-counter medications are nonexistent. People who need medicine go to doctors for it, making the request by pointing to picture labels on the bottles because many Haitians remain illiterate.

[hotblock]

Still, medication, physicians and hospitals are few in the island nation. Most people can’t afford to access a doctor so illnesses easily cured in the United States go untreated in Haiti.

Joe Ferrara, an American doctor who attends the trips with Our Lady of Mount Carmel’s mission, said a middle-aged woman suffering from eye-harming glaucoma couldn’t find eye drops until provided by a local clinic.

Eyeglasses, however, change not just a person’s vision in Haiti, but also people’s outlook on life. Overjoyed Haitians hugged a nervous eyeglass distributor who was in charge of passing them out for testing.

Treating Haitian patients is difficult because disease contaminates the water in the pipes of Port-au-Prince. Patients recuperate, drink the water and get sick again, hence the development of a crude clean-water program in which water is filtered and carried in buckets on foot from home to home.

The parish mission, which organizers said was inspired initially by a long-winded homilist at a Mass, has grown from meeting medical needs to include sponsorship of kids seeking education. Now a trade school is being developed in St. Jude Parish to train students to staff the returning Haitian hotel industry. General managers plan to hire students schooled in hospitality.

The mission also now provides house calls for shut-ins.

It has also seen the completion of St. Jude Church, fashioned with American wooden pews and a roof, along with a medical clinic building.

The church acts as the parish’s main center of activity. Initially housing the original clinic, it now also includes a pediatric facility.

[hotblock2]

The parish buildings stretch extensively throughout the city neighborhood. The St. Jude rectory grounds house residents in cinder block huts behind the building on the uphill edge of the property. Father Terry Weik, a parochial vicar at Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish, said the Haitian rectory promotes a safe feeling for visitors with its scaling walls and guard dogs.

The local people serve their missionary friends ice-cold beer in humble homes adorned with simple curtains. Worshipers had carried a cinder block used to build their home down the church aisle as the parish erected the building.

The mission gained the Haitians’ trust by respecting cultural differences while also breaking down walls of misunderstanding. The Doylestown Catholics also helped counteract the catastrophic destruction from the January 2010 earthquake that killed hundreds of thousands of people in Haiti.

It struck during the consecration of the Eucharist at Mass and the disaster caused the St. Jude pastor to question whether it meant the end of him and his congregation. It did not, of course, but a hole still remains in the church wall from the earthquake

The mission seeks hope in a desolate place, privy to both doubt and miracles. Haitian streets remain unpaved and the water dirty.

Finding progress is sometimes tough for Americans, but from the Haitian standpoint, even one traffic light gives the sense of a better future in a country where electricity is inconsistent, missionaries must bathe with baby wipes and children often walk hours to attend school, one of which is a long jeep ride away in the mountains.

One night before a mission trip to Haiti, Kardish received a knock on his door from a family at his Pennsylvania home. A little girl had a note for a Haitian friend that she wanted delivered.

Kardish scoffed at the odds of finding the intended recipient. But he found the poor girl living with another family — her own had sent her off to rid them of the expense — at a little school near the church.

“You can’t underestimate what small action could turn into something great,” Kardish said.

***

Brendan Monahan is a freelance writer in Plymouth Meeting. He may be emailed at bmonahan16@gmail.com.

At a Mass in St. Jude Church in the Haitian capital, Missionhurst Father Andrew Labatorio preaches the homily for the congregation that included parishioners of the Port-au-Prince parish and visitors from Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish in Doylestown, including Father Terry Weik (far left) who concelebrated.

PREVIOUS: Experts discuss race relations after Ferguson

NEXT: Night of music, praise and prayer coming to abbey

Share this story