A staffer with the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia sets up an exhibit charting the growth of religious liberty in the United States.

History is a funny thing. Not quite a century ago New York’s Catholic Governor Al Smith lost the 1927 presidential election by a landslide, partly because of his religion and the canard, “He will bring the pope to America.”

Since then we’ve have nine papal visits, including a couple of refueling stops — one by Pope Paul VI, seven by Pope John Paul II and one by Pope Benedict XVI. Now we are about to have our 10th, which will be Pope Francis.

Coming for the September World Meeting of Families, he will be the second reigning pontiff to visit Philadelphia, providing he gets through the security gauntlet.

In honor of this truly significant event, many of the city’s civic institutions and museums are hosting special displays to honor this visit.

One of the most important of these is an exhibit by the National Constitution Center, “Religious Liberty and the Founding of America,” which through assembled documents explores the development of the concept of Freedom of Religion as it developed in the 13 original colonies, beginning with “Religious Liberty in Colonial America,” continuing with “Religious Liberty in the Constitution,” and “The Legacy of Religious Liberty.”

In honor of the visit by Pope Francis, “We decided to make religious liberty the theme for the entire fall,” said Jeffrey Rosen, president and CEO of the National Constitution Center.

The exhibit runs from Aug. 21 through Jan. 3, 2016.

[hotblock]

One of the paradoxes is that many of the early settlers, for example the Puritans in Massachusetts, came to America to be free to worship God according to the tenets of their own faith but banned or persecuted those with different beliefs.

“Nine of the original 13 colonies had established churches,” Rosen said. “Many of them levied taxes to support the church, some only allowed members to hold public office. Some believers — Catholics, Baptists, Jews — faced discrimination. We have early charters that preached religious freedom but barred non-Protestants from holding office.”

Generally speaking, the only two colonies that practiced freedom of religion up to the Revolutionary War without interruption were Pennsylvania and Rhode Island, although in Pennsylvania the Charter of Privileges of 1741 protected anyone who believed in a monotheistic religion but limited public office to those who believed in Jesus Christ. This exception may not have been enforced.

Colonial Virginia did have a test oath for office, which included a denial of Catholic doctrine, and among the signers of this was a young George Washington.

“That document is displayed next to George Mason’s inspiring Virginia Declaration of Rights, which inspired both Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence and Madison’s Bill of Rights,” Rosen said.

“That document is displayed next to George Mason’s inspiring Virginia Declaration of Rights, which inspired both Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence and Madison’s Bill of Rights,” Rosen said.

Mason’s Declaration of Rights, dated June 12, 1776, states “That religion, or the duty which we owe to our CREATOR and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love and charity towards each other.”

Another important document that was a precursor to the religion clause of the Bill of Rights was the New York Constitution, passed in 1777 and also part of the exhibit. It was the first example of a freedom of religion clause after the colonies declared independence, which is also part of the display, according to Rosen.

In this document it is stated, “this convention doth further, in the name and by the authority of the good people of this State, ordain, determine, and declare, that the free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference, shall forever hereafter be allowed, within this State, to all mankind: Provided, that the liberty of conscience, hereby granted, shall not be so construed as to excuse acts of licentiousness, or justify practices inconsistent with the peace or safety of this State.”

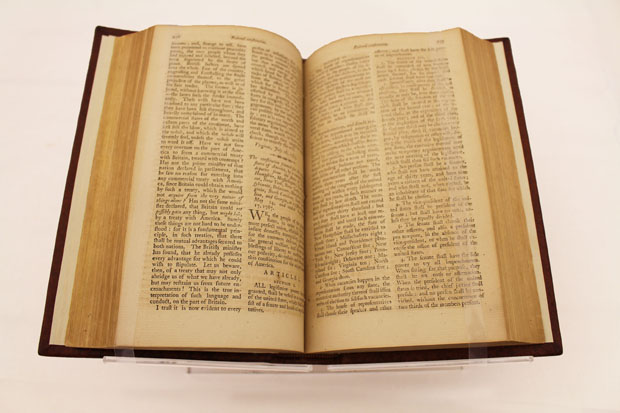

Which of course, leads us to the greatest document of them all, which is also displayed. This is the Constitution of the United States, effective 1789, with its lofty amended Bill of Rights added in 1791, essentially authored by James Madison. Amendment I states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof ….”

[hotblock2]

Technically, Rosen notes, this did not ban religious discrimination throughout the country. It only banned the federal government from passing discriminating laws, although the several states did follow suit in their own constitutions and eventually the 14th amendment gave the federal government greater enforcement powers to supersede state laws.

As noted, as a young man George Washington did sign a discriminatory test oath necessary for public office, but as president, his actions displayed absolute agreement with freedom of religion.

There are two letters from Washington in the display. One is a response to a congratulatory letter from the Catholic community in which he wrote, “All that conduct themselves worthily are entitled to equal protection by the Federal Government ….”

In a letter to the Jewish community, he wrote, “The Government gives to bigotry no sanction,” and with biblical allusion to Micah 4:4, “Everyone shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree. There shall be none to make him afraid.”

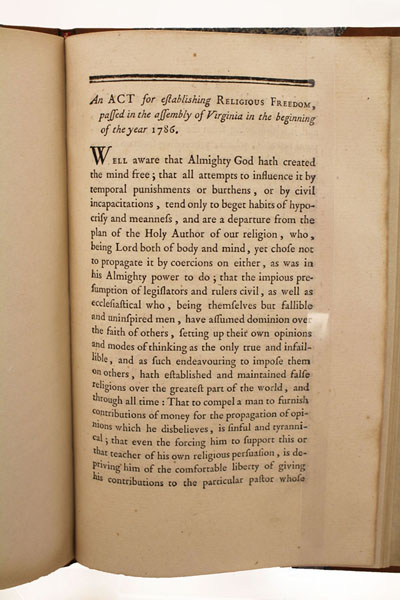

A book citing Virginia’s religious freedom provision from 1786 is part of the National Constitution Center’s exhibit on the subject.

Today, when people choose to cite the First Amendment to the Constitution, they often as not refer to Thomas Jefferson’s interpretation as “a wall of separation between Church and State,” meaning there should be no interaction whatsoever between the two.

It is questionable how many of Jefferson’s contemporaries would accept that meaning. Both George Washington and his successor John Adams proclaimed a day of prayer in thanksgiving or reparation to God. Thomas Jefferson, the third president, refused to do so citing in an 1802 explanation to the Baptists in Danbury “the wall of separation” raised by the First Amendment.

But Jefferson was succeeded in the presidency by James Madison, the prime author of the Bill of Rights. In 1812 after a petition by both Houses of Congress, in a proclamation Madison wrote, “I do therefore recommend the third Thursday in August next as a convenient day to be set apart for the devout purposes of rendering the Sovereign of the Universe and the Benefactor of Mankind the public homage due to His holy attributes .…”

While good people may quibble over the exact meaning of phrases, beyond doubt the United States Constitution with its Bill of Rights including the religious freedom clause has been emulated by many countries around the world.

In a sense this fundamental freedom was officially recognized by the Roman Catholic Church through the Vatican II document Dignitatis Humanae promulgated by Pope Paul IV on Dec. 7, 1965: “2. This Vatican Council declares that the human person has a right to religious freedom. This freedom means that all men are to be immune from coercion on the part of individuals or of social groups and of any human power, in such wise that no one be forced to act in a manner contrary to his own beliefs, whether privately or publicly, whether alone or in association with others, within due limits.”

It is appropriate that the National Constitution Center’s religious liberty display coincides with the visit to Philadelphia by Pope Francis, although this is not the only reason for the exhibit. It also honors the October visit to Philadelphia of the Dalai Lama, the exiled spiritual leader of Tibet who will receive the annual Freedom Medal. It is a reminder that real religious freedom is not yet universally practiced.

***

For more information on the National Constitution Center and the Religious Liberty and the Constitution display visit www.constitutioncenter.org.

PREVIOUS: Los Angeles archbishop to speak on immigration at congress’ last day

NEXT: The family and its mission; one month and counting

There is no such thing as “religious liberty” You are obligation to submit to God and no other gods beside HIM.