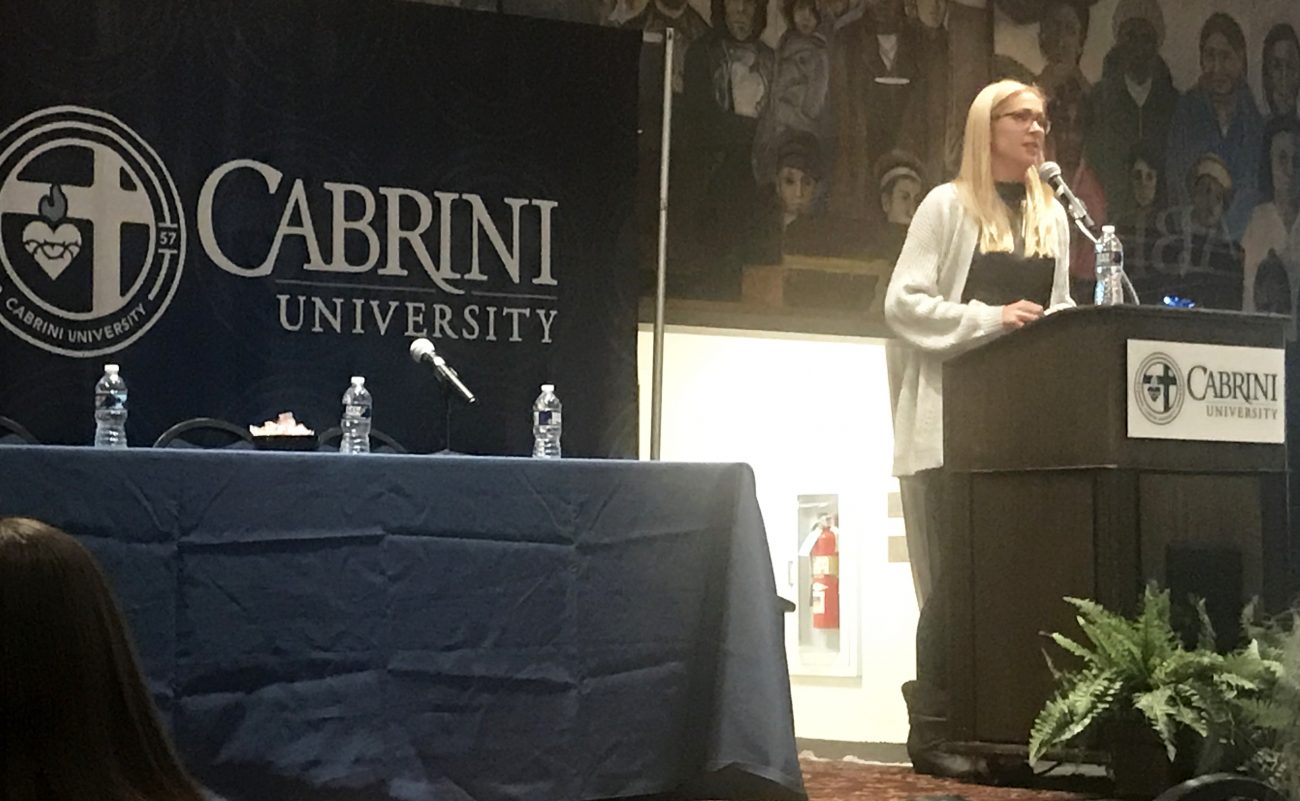

Activist and human trafficking survivor Tammy McDonnell shares her personal stories and message of hope with students and community residents Nov. 6 at Cabrini University, Radnor. (Photo by Gia Myers)

Human trafficking survivor Tammy McDonnell shared her experiences Nov. 6 at Cabrini University and, through a panel discussion that followed, raised awareness among students and residents about the crime of trafficking — a form of modern-day slavery — its prevalence in Philadelphia-area communities and how to combat it.

Human trafficking occurs when force, fraud, or coercion is used to control another person for the purpose of engagement in commercial sex acts or soliciting labor or services against that person’s will.

The three most common forms are sex trafficking, debt bondage and forced labor, also known as involuntary servitude, which is the largest sector of trafficking in the world, according to the U.S. Department of State.

[hotblock]

“Slavery is death,” said McDonnell, who is also an activist for Covenant House in Philadelphia. Human trafficking treats people as disposable, she said.

“Trafficking happens in your own backyard,” she said, adding that it is so prevalent, “you can be sitting next to a survivor, and not even know it.”

McDonnell described her younger self as someone who “played basketball and was a straight A student.” However, having been molested at 5 years of age, she struggled with feelings of low self-esteem, describing herself as a “people pleaser” whose “self-worth was non-existent. I felt that I was never enough.”

McDonnell said she started experimenting with drugs in high school when at a party, she was offered a Percocet pill, a narcotic pain killer, and this led to a drug addiction that lasted for many years.

At age 21, she became involved in a “controlling and abusive relationship” with the man who became the father of her first child, a son. “He isolated me from my family. I went into this world where the abnormal became normal. I went into this dark world.”

After that relationship ended, she entered a treatment program, and there met a man who was also in recovery. They had what she described as a “rehab romance.” He became the father of her second child, a daughter. When that relationship ended, she realized, “I had two kids, a drug problem, and didn’t know how to live.”

Her human trafficking story began when she sold her car for $800 to a man that she now realizes was a “recruiter,” an intermediary who referred her to someone who could give her a job that she needed, which “was the start of everything.”

[tower]

The job was at a Philadelphia auto body repair shop, where McDonnell was hired as a secretary. Since she had no place the live, the man who was her employer and later her trafficker, said she could “sleep in the office as long as I worked for him. I was just tired, and I wanted a place to stay.”

After some time had passed, the employer stopped paying McDonnell. “But I still had to work for him. I was forced to have sex with him and anyone (else) he wanted.”

McDonnell talked about being locked in a closet and forced into withdrawal. “I prayed for my own death,” she said. “I didn’t know anything about sex trafficking. I thought it was all my fault because of my drug addiction.”

Looking back, she now realizes her trafficker was a predator who took advantage of her vulnerabilities. She felt trapped and was too afraid to break away because she needed to protect her family from the trafficker, who made threats against her mother and her children.

Then one day, she said, “this cosmic mental switch went off, and I said, ‘I’m done.’” She fled Philadelphia for New Jersey, where she was homeless and subsisted by committing petty theft crimes, such as breaking into parked cars and stealing items which she sold to purchase food and drugs.

“I slept on the beach, and it’s not as nice as it sounds because it gets cold at night,” she said. She ultimately returned to Philadelphia and entered a crisis facility in Center City.

“I’ve been sober for four years and 30 days,” she said. “I had no idea I was a victim of human trafficking. I just thought I was in an abusive situation.”

The crisis center referred McDonnell to a women’s recovery program, where she lived with Catholic nuns for 18 months. During her recovery, one of the sisters recommended McDonnell for a position as survivor advocate for Covenant House in Philadelphia. Now, her role has been expanded also to include outreach worker.

“I can raise awareness because it’s so necessary,” McDonnell said. She advocates for laws to prevent human trafficking in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. “I knew nothing about the law, except how to break it.” But now she attends community college, pursuing paralegal studies, and hopes eventually to attend law school. “My life is helping other people,” she says.

A panel discussion of anti-human trafficking advocates Nov. 6 at Cabrini University included, from left: Lindsey Mossor, anti-human trafficking staff attorney at Nationalities Service Center in Philadelphia; Maggie Sweeny, program manager and forensic interviewer for Mission Kids Child Advocacy in East Norriton; Connie Marinello, detective in the investigations Division of the Upper Merion Township Police Department; and Habibah Smith, co-chair of Delaware County Anti-Human Trafficking Coalition.

In the panel discussion that followed McDonnell’s talk, Connie Marinello, a detective in the Investigations Division of the Upper Merion Township Police Department, said it’s important to keep in mind that the majority of people involved with prostitution are victims and not working of their free will.

“For years, we were arresting prostitutes,” she said. “We need to reverse the mindset of law enforcement. We have to understand (these people) are not the criminals. They’re the victims, and we need to go after the traffickers.”

Lindsey Mossor, the anti-human trafficking staff attorney at the Nationalities Service Center in Philadelphia, talked of the challenges in helping victims of human trafficking. “It’s really difficult to engage this demographic because so many people have violated them,” she said.

“They don’t see themselves as a victim,” said Habibah Smith, co-chair of the Delaware County Human Trafficking Coalition. “It’s another level of trauma. They think the problem is a bad relationship, bad people, or a bad situation.”

In an effort to combat human trafficking in local communities, Mossor’s organization is “getting the word out that this is happening, and this is what it looks like,” she said. Educating the community is key, so people can identify the “red flags” of trafficking, she said.

“Relationships are key,” said Smith. “Traffickers enter the situation in some sort of relationship,” but these are not healthy relationships with healthy boundaries, she said. “Things happen that our victims don’t recognize as red flags.” Human trafficking has similarities to domestic violence and addiction, Smith added.

To help prevent human trafficking, Mossor advised, “Don’t buy sex. Think about where your services are coming from. Notice the people in your neighborhood.”

“Get the word out that this is happening,” said Maggie Sweeny, program manager and forensic interviewer for Mission Kids Child Advocacy Center in East Norriton. “We’re going to shine a light on it.”

If you suspect a human trafficking situation in your community, said Marinello, call the National Human Trafficking Hotline toll-free at 1-888-373-7888 or go to www.humantraffickinghotline.org, and call your local police department.

Catelynn Rios, a sophomore student at Cabrini, found inspiration in the discussion, saying, human trafficking “happens all the time. If I see red flags, I can do something about it.”

Members of the Cabrini University community gathered Nov. 6 to learn about human trafficking in the local area and what they can do to combat it.

PREVIOUS: New senior center reminds older adults ‘they’re worth it’

NEXT: Wayne-based executive named to national Catholic council

Share this story