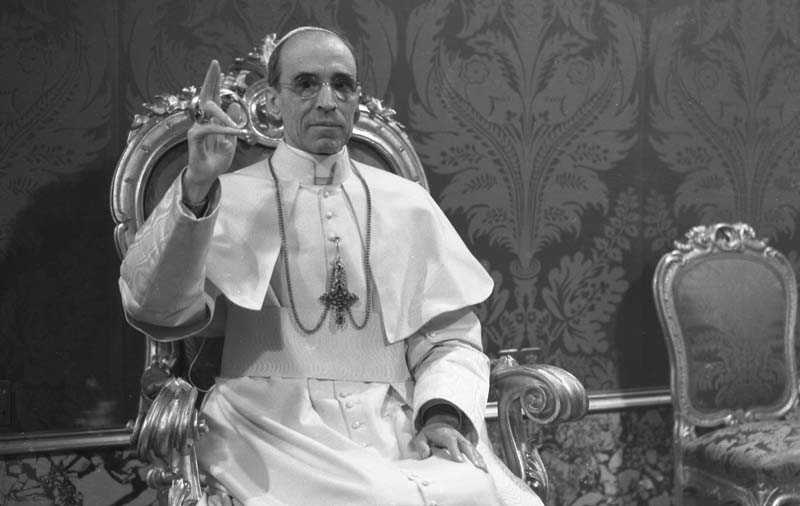

Pope Pius XII, who led the Catholic Church from 1939 to 1958, is pictured in this undated photo at the Vatican. The 2020 opening of Vatican Archives from the wartime pontificate will ultimately reveal a complex, nuanced picture of the Catholic Church’s response to Nazi persecution of Jews, according to scholar Suzanne Brown-Fleming. (CNS photo/Vatican Media).

Recently unsealed Vatican archives on World War II and Pope Pius XII will ultimately provide “a very complex picture with a lot of flawed characters on all sides,” according to an acclaimed researcher.

Dr. Suzanne Brown-Fleming, director of international academic programs at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), shared her insights during a Nov. 9 webinar hosted by the Institute for Jewish-Catholic Relations (IJCR) at St. Joseph’s University.

Founded in 1967, the IJCR is the oldest university center of its kind in the U.S. created in response to the Second Vatican Council’s call for increased interfaith dialogue.

The talk took place on the 82nd anniversary of Kristallnacht (German for “Crystal Night”), a Nazi-ordered attack on Jewish persons and property throughout Germany that resulted in the destruction of more than 1,000 synagogues and 7,500 Jewish businesses. At least 100 Jews were killed outright, with another 30,000 men aged 16 to 60 arrested and deported to concentration camps.

The 1938 pogrom — widely considered the opening of the Shoah, the preferred Hebrew term for the Holocaust – was marked by a moment of silence prior to Brown-Fleming’s presentation.

[hotblock]

The webinar, which was moderated by IJCR directors Philip Cunningham and Adam Gregerman, served as a follow-up to the ICJR’s March 3 screening of “Holy Silence,” a 2020 documentary by Steven Pressman that examined key individuals who shaped Vatican response to the rise of Nazism.

Controversy has long marred the legacy of Pope Pius XII, whose 1939-1958 pontificate coincided with World War II, the Shoah and postwar reconstruction. Six million Jews were systematically killed by Nazi Germany during the Shoah, and Pope Francis has previously acknowledged his predecessor experienced “moments of tormented decisions … which to some could look like reticence.”

Brown-Fleming appeared in Pressman’s film, the release of which unintentionally coincided with the Vatican’s March 2 opening to scholars of a vast archival collection on Pope Pius XII.

Although access to the 16 million documents has been hampered by COVID restrictions, Brown-Fleming (who reviewed several items in October) said the collection will help redress what until now has been a “bifurcated picture” of the Catholic Church’s response to Nazi persecution of the Jewish people.

Suzanne Brown-Fleming, director of international academic programs at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed documents from the Vatican’s newly opened Pope Pius XII archives in October 2020. (Zoom/Institute for Jewish-Catholic Relations)

“Ever since the early 1960s … there hasn’t been one storyline, but two,” she said.

While both sets focus heavily on Pope Pius XII and, to a lesser extent, his predecessor Pope Pius XI, “one … tells a narrative that the Catholic Church was under duress itself,” said Brown-Fleming.

In the face of increased Nazi repression, concern for the ability to provide the sacraments and to preserve the institutional church and Catholic life motivated clerical leaders to adopt a “strict adherence to neutrality,” she said.

The Catholic Church was also “very fixated on what it perceived as the dangers of communism,” said Brown-Fleming, noting that while papal nuncio to Germany, then-Archbishop Eugenio Pacelli – the future Pope Pius XII – had himself witnessed a communist uprising in 1919.

At the same time, said Brown-Fleming, “there’s another narrative that is very, very critical of the lack of specificity about Nazism and about mentioning Jews … (by) one of the best-informed institutions in the world.”

During his nunciature, Archbishop Pacelli negotiated several concordats to ensure church freedom, including a 1933 agreement with the Third Reich. In 1937, he helped to draft Pope Pius XI’s anti-Nazi encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge (“With Deep Anxiety”), which denounced racial persecution, but – like a later church statement in response to Kristallnacht — averted direct mention of Adolf Hitler or the Nazi party.

[tower]

Equally problematic, said Brown-Fleming, are questions surrounding Pope Pius XII’s knowledge of Nazi persecution at his doorstep, such as the October 16, 1943 roundup of more than 1,000 Roman Jews who were deported to Auschwitz, where all but 16 perished.

“What happened that day?” she said. “There was no formal protest by the pope.”

She expressed hope the archives will also help determine to what extent Pope Pius XII was aware of the “ratlines,” the escape routes that permitted Nazi war criminals to evade capture by fleeing via Italy to South America.

“It was so known (and reported) in the papers,” said Brown-Fleming. “We don’t know if they condoned it, turned a blind eye or (provided) finances.”

At work in both narratives regarding the church’s stance was a centuries-old “teaching of contempt” for Jews, who were denounced as the murderers of Christ, she added.

The Second Vatican Council — which in the document Nostra Aetate denounced anti-Judaism and affirmed that “God holds the Jews most dear” – brought about a “sea change” in perspective, said Brown-Fleming.

“For people like me, who grew up after Vatican II, religions are to be accepted. I never heard negative teaching about Jews while I was growing up,” said Brown-Fleming, herself a Catholic.

During World War II, seeds of that change were already evident in a number of lay, clergy and religious “who were able to not follow what they’d been taught (about the Jews) … who rescued them, and wrote to the pope” asking for his intervention, she said.

A prominent example can be found in Archbishop Angelo Roncalli, the future Pope John XXIII, who protected Jews while serving as papal nuncio to Turkey, said Brown-Fleming.

Yet she warned that some of the archival documents “will bring to the fore some very, very tough conversations.”

One particular issue that has troubled her for years was the papal blessing extended (at the request of Father Costatino Pohlmann) to convicted Nazi criminal Oswald Pohl just before his execution in 1951.

Although Pohl claimed he had returned to the Catholic faith after the war, “I struggle with that forgiveness,” admitted Brown-Fleming. “We need evidence that Catholics involved in the Holocaust – and there were millions – actually were sorry, and recognized what they had done.”

In the coming years, she said, research will reveal “a much more nuanced, honest story” about the Catholic Church’s response to the Shoah.

“And it’s my hope that Jewish-Christian relations are strong enough at this point for really honest conversations about what we find,” she said.

PREVIOUS: New state tax credit will help archdiocese build more homes for seniors

NEXT: Catholic schools going all virtual in Montgomery County

Share this story