They were Poles, Austrians, Germans, Czechs, Italians, Irish — especially Irish — and they had one thing in common. They were Catholics, many of them new immigrants but loyal Americans.

Seven score and 10 years ago, as Abraham Lincoln might say, many of them participated in the crucial Battle of Gettysburg July 1-3, 1863, and some of them are among the honored dead President Lincoln memorialized one year later in his famous address.

Certainly Catholicism was still very much a minority religion in 19th century America, but Catholics were there. Just exactly how many of them fought at Gettysburg is impossible to say, according to Dr. Anthony Waskie, a Temple University professor and member of St. Laurentius Parish in Philadelphia, who is the principal author of “Philadelphia and the Civil War: Arsenal of the Union” published in 2011.

[hotblock]

Religion was not a statistic kept by the military, and one of the best determinants is the nationality of the soldiers who comprised a unit. One of the most famous such units was the Irish Brigade which in 1862 participated in several battles including Antietam and Fredericksburg.

By 1863 at the time of Gettysburg it was commanded by Brigadier General Patrick Kelly, a New Yorker who later was killed at the siege of Petersburg.

“Three of the regiments were from New York, one was from Boston and one was from Pennsylvania,” Waskie explained. “The Pennsylvania regiment was the 116th led by Colonel St. Clair Mulholland. He was an Irish immigrant and quite well educated. He was the recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor for the Battle of Chancellorsville.”

Eventually he would rise to the rank of major general in the volunteer service. After the war he became active in Philadelphia politics and was Philadelphia’s chief of police, and he is buried in Old Cathedral Cemetery.

A print depicts Holy Cross Father William Corby, who traveled with a regiment from Boston, giving general absolution to the Irish Brigade on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg. (PAHRC)

During the battle, the Irish Brigade helped defend the Wheatfield against charges by General James Longstreet’s troops.

The Boston Regiment brought a chaplain with them to Gettysburg — Father William Corby, C.S.C. A memorable event of the battle was Father Corby standing on a rock giving his Irish troops general absolution. Years later, through the efforts of St. Clair Mulholland, a statue showing Father Corby giving absolution was erected on the very rock where he stood.

A bit after the war he was named president of Notre Dame College, in South Bend, Indiana. A duplicate statue was later erected on the campus and at that somewhat football-mad school the statue is popularly known as “Fair Catch Corby” because of his raised hand.

“The 69th Pennsylvania was not in the Irish Brigade, but they were overwhelmingly Irish and they suffered very heavily at Gettysburg,” Waskie said.

During Pickett’s Charge the regiment lost 143 men out of 248 including its colonel, a lieutenant colonel, two captains and a lieutenant.

(See a letter written by Pennsylvania 69th soldier William White to his family. The letter describes the battle and includes a reference to July 3 recounting Pickett’s Charge.)

The 58th New York, organized by Col. Wladimir Kryzanowski, in 1861, was known as the Polish Legion and had many Catholics, Waskie said. It also included Germans, Danes, Italians, Russians and French. It saw action in many campaigns, and by 1863 while under the command of Lieutenant Colonel August Otto, it helped to defend Cemetery Hill at Gettysburg.

Colonel Federico Cavada, commanded the 114th Pennsylvania, and his brother, Captain Alfonso Cavada, were raised in Philadelphia with a Cuban father and American mother. Both served as Gettysburg, and Federico was captured by the Confederates. After the war the Cavada brothers returned to Cuba to fight for independence from Spain. Both were killed in 1871.

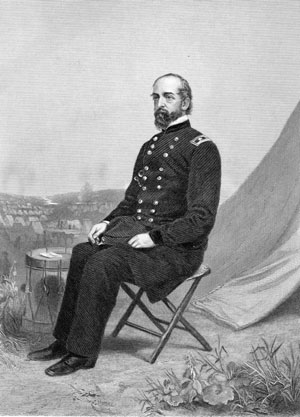

General George Gordon Meade, commanding general of the Union’s Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg, was raised Protestant but hailed from one of Philadelphia’s first Catholic families. (PAHRC)

The Commanding General of the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg was George Gordon Meade, a member of what was one of Philadelphia’s first Catholic families. Although he was born Catholic, he was raised Protestant by his mother after the death of his father.

On the other hand, General John F. Reynolds, of Lancaster, Pa., was not a Catholic. Killed by a sniper on the first day of the battle, his family was startled to discover he had a cross on his neck. It seems he was secretly engaged to a young Catholic girl, Kate Hewitt (herself a convert). Shortly after his death Kate entered the Sisters of Charity, where she remained for about five years but left before taking her vows.

There were probably a fair number of Catholics in the Confederate armies also, “especially if they were from Louisiana,” suggests Waskie.

Lieutenant General James Longstreet was neither a Louisianan nor a Catholic.

At Gettysburg he disagreed with tactics proposed by General Robert E. Lee but nevertheless followed the orders that led to Pickett’s Charge and ultimate defeat.

After the war he angered his fellow Southerners by wholeheartedly embracing Reconstruction. It didn’t help matters when he converted to Catholicism in 1877 and remained a strong Catholic until his death in 1904.

Another Catholic presence at Gettysburg were about a dozen Daughters of Charity, nursing on the battlefield. “They had a priest with them, Father Francis Burlando, a Vincentian,” Waskie said.

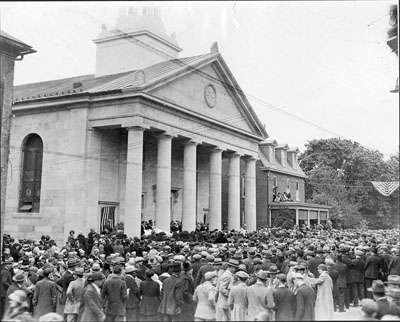

In Gettysburg, which today is served by the Catholic Diocese of Harrisburg, St. Francis Xavier Church became a battlefield hospital.

Stained glass windows in the church depict scenes of wounded soldiers being cared for by Catholic nuns. The celebration of an outdoor field Mass commemorating the dead and wounded has long been a tradition for the parish.

St. Francis Xavier Church in Gettysburg, today part of the Diocese of Harrisburg, served as a military hospital during the battle. This photo from the early 20th century depicts the dedication of a memorial at the church to the dead and wounded of the battle. New York Cardinal Timothy Dolan will celebrate a memorial Mass at the church July 6. (PAHRC)

In fact, history buff and Archbishop of New York, Cardinal Timothy Dolan, will celebrate a Mass marking the 150th anniversary of the battle July 6 at 7 p.m. at St. Francis Church, located at 455 Table Rock Road in Gettysburg.

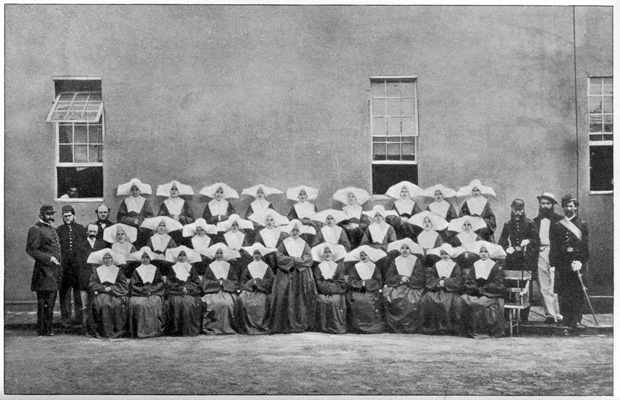

For the most part the sisters did not nurse on the battlefield, but in the huge military hospitals that sprang up both in the North and the South. While many congregations supplied sister-nurses during the conflict, the Daughters of Charity were the most active, even to the point of temporarily closing schools for lack of remaining teaching sisters.

In Philadelphia there was the Satterlee Military Hospital (1862-65) in West Philadelphia and in Chestnut Hill the Mower Military Hospital (1863-65). The Satterlee had 4,500 beds and the Mower had 3,600 beds.

By comparison both were larger than the four largest hospitals combined in today’s Philadelphia.

Shortly after the Satterlee opened, Sister Mary Gonzaga Grace, who was missioned to St. Joseph’s Orphan Asylum in Philadelphia, was asked to take charge of the Daughters of Charity who would serve as nurses at the hospital.

“The men really loved her, she was legendary, and afterwards the men would write to her,” Waskie said.

Initially there were 42 sisters; over the next three years the total number of sisters who served at the hospital at various times was 91.

When the sisters arrived, the newly constructed hospital had about 900 patients. Within a couple of months that rose to 1,500 especially after the Battle of Second Bull Run.

Soldiers, after being stabilized at field hospitals, were brought up from Virginia by train. Some were wounded, others were suffering from swamp fever, chronic dysentery, typhoid fever and even small pox, Sister Mary Gonzaga wrote.

Because small pox was so contagious, the sisters were not allowed to minister to the victims at first, but they found one of their sisters who previously had the disease and was now immune who could nurse these men.

The real trial came after the Battle of Gettysburg, when the hospital population rose to more than 5,000 with the overflow housed in tents.

One sister, Sister Margaret Hamilton, wrote, “When they arrived at the hospital many wounds were full of vermin and in many cases gangrene had set in. The odor was almost unbearable. The demand on our time and labor was so increased that the number of nurses seemed utterly inadequate and the hospital presented a pure picture of the horrors of war.”

Most amazing of the more than 6,000 wounded and sick that passed through Satterlee Hospital in the month or so after Gettysburg, only 110 died.

It was all thanks to the dedicated doctors and the heroic sister-nurses led by Sister Mary Gonzaga. It was a pattern repeated at hospitals all over the country, both North and South.

***

Lou Baldwin is a freelance writer in Philadelphia.

PREVIOUS: CatholicPhilly.com wins two national Catholic awards

NEXT: St. John’s Hospice marks 50 years of serving the homeless with gala

Share this story