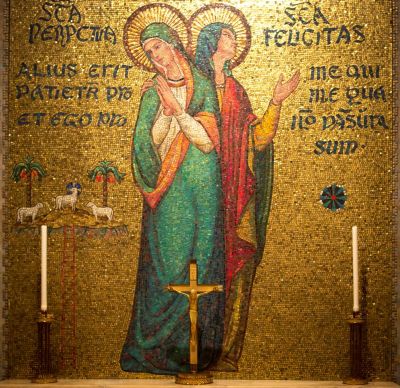

A mosaic of martyrs Perpetua and Felicity adorns a chapel wall in the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, in this Sept. 28 photo. The early Church Mothers — like the Church Fathers of whom we’ve heard so much — were influential in the first few centuries of our Christian development. (CNS photo/Chaz Muth)

There’s an old saying, “The hand that rocks the cradle rules the world.”

When I grew up, women were often not given their due, so this quote seemed like a testimony to our importance, albeit often behind the scenes.

To women, it’s been no secret that our spiritual and intellectual gifts have been important to the church throughout history. But that fact has been underestimated. And as the above quote implies, women’s power was often considered to be purely exerted on the domestic side.

Happily, research and writing on the church has begun to more clearly celebrate the intellectual and spiritual power of women in early church history. The early Church Mothers — like the Church Fathers of whom we’ve heard so much — were influential in the first few centuries of our Christian development.

Why haven’t we heard more about these strong and powerful women? One reason is that because of the culture of the times, women were not often writers. Nor were they regarded as having power. After all, he who writes history controls what it says.

One writer who is delving into this female history is Mike Aquilina, who wrote, “The Witness of Early Christian Women: Mothers of the Church.”

[hotblock]

What this author points out is something that should be obvious when we read about Jesus in the Gospels: Christianity took a revolutionary approach to the treatment of women.

The Greco-Roman standards of the time suggested baby girls could be discarded if unwanted, their lives of much less value than sons.

And Jesus lived in a Jewish community where women were under the complete authority of men — their fathers, then their husbands. Essentially second-class citizens, they did not always experience legal equality in court.

And yet we see Jesus talking with the Samaritan woman, challenging the punishment of the woman caught in adultery, counting many women among his followers. And who did he appoint to give testimony of his resurrection to his apostles? That great woman of the Gospel, Mary of Magdala.

Christianity opened the door to recognition of women’s dignity.

Then, Aquilina points out, Paul proclaimed this extraordinary assertion in his Letter to the Galatians: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free person, there is not male and female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

No wonder early women in the church took up the mantle of Christianity with gusto.

Who were these women?

We’re all familiar with the names of Perpetua and Felicity, two brave young women martyred by the Romans. Many of the early female heroes were martyrs.

But there were also many noted for their intellectual attributes. St. Macrina was the older sister of the famous bishop Gregory of Nyssa, noted for his theology and mysticism. But it was his sister whom he credited as his teacher.

Then, of course, there’s St. Monica, the hope of mothers everywhere, who prayed for and instructed her wayward son Augustine until finally he became one of the pre-eminent saints of Christendom.

There’s Thecla of Iconium, a convert and wealthy first-century woman who followed Paul despite her family’s adamant and sometimes violent displeasure. She started her own mission in Seleucia of Isauria, and a mural of her alongside St. Paul testifies to her importance in the early church and to the fact that leadership in the early church was not exclusively a male affair. The list goes on.

[hotblock2]

The author Kathleen Norris is a Benedictine Oblate who has written extensively on the early Desert Fathers and Mothers who went, literally, into the desert to preserve the asceticism of early Christianity after its acceptance as the official religion of the Roman Empire.

In books like “The Cloister Walk” and “Dakota,” Norris tells touching stories, sometimes shrouded in myth, of these early “abbas” and “ammas.”

It’s important to our understanding of faith that we recognize these early founders. And keep in mind that without the “ammas,” the picture’s not complete.

(Caldarola is a freelance writer and a columnist for Catholic News Service.)

Share this story