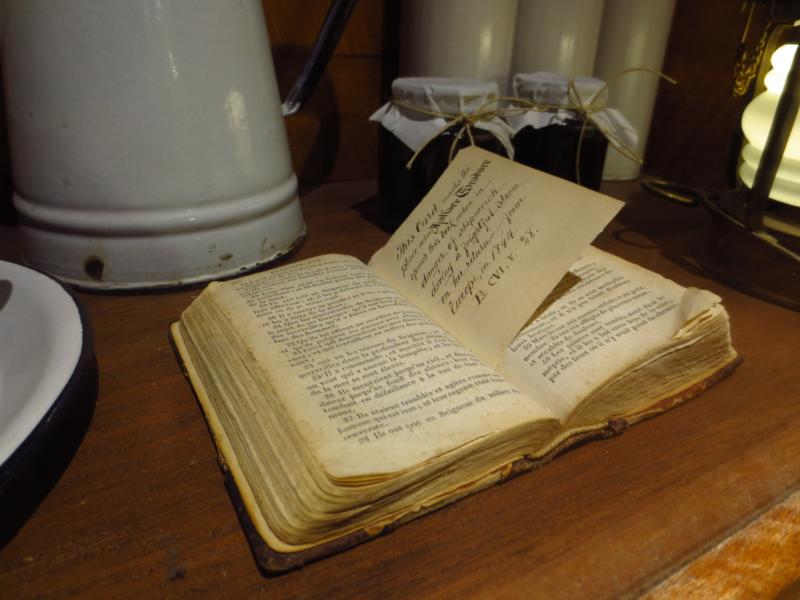

A Book of Psalms used by St. Mother Theodore Guerin is on display at her shrine Oct. 6, 2016, at the Sisters of Providence of St. Mary-of-the-Woods, Ind. Praying with the seven penitential psalms during Lent can help bring about conversion of heart and mind. (CNS photo/Katie Breidenbach)

The cross of ashes traced on our forehead on Ash Wednesday invites us to “repent, and believe in the Gospel.” Lent calls us to examine our lives, assess our relationship with God and discover where we need to set things right.

Our Lenten prayer might include sorrow for sin and requests to God to help us to bring about the change in our mind and heart that we call conversion. Our tradition offers prayers whose words we might “borrow” to help us along — the seven penitential psalms (Pss 6, 32, 38, 51, 102, 130, 143).

[hotblock]

The Book of Psalms originated not as a single book, but as something like the hymnal you use at Mass: a compilation of several smaller collections assembled over a long period of time. That the penitential psalms are spread throughout the Book of Psalms, not grouped together within a subcollection, suggests that sorrow for sin is a part of the human condition that can assert itself in many different contexts in an individual’s life.

Tradition associates the psalms with King David. David initiated the process of compilation that eventually produced the Book of Psalms. He is also believed to have composed some of the psalms, including one of the penitential psalms, Psalm 51, “Miserere mei.”

Composed after David had sinned by seducing Bathsheba, Psalm 51 has all the elements of an act of contrition: It appeals to God’s mercy; acknowledges one’s sin; pleads to God for wisdom; and recognizes that God prefers a humble, contrite heart to adherence to outward ritual. Psalm 51 appears frequently in our Lenten liturgy, beginning with Ash Wednesday’s responsorial psalm.

Human life is complex and varied, and these psalms reflect this in the way each emphasizes a different context for expressing penitence. Yet, certain themes are common to a few or most of these psalms.

Psalms 6, 32, 38 and 102 emphasize an important psychological truth: the effects of guilt on our physical health and other unresolved spiritual issues. Psalm 32 expresses the relief that comes from honestly acknowledging one’s sin to God; I like to use this psalm as a prayer of thanksgiving after confession. Other psalms describe how one’s strength (6, 102) and health (38) are sapped by guilt.

[hotblock2]

The effects of sin can include alienation from other people as well as from God. The psalmist is avoided by friends (38) and reviled (102) and persecuted (143) by enemies.

Psalm 143 serves as a good introduction to praying with imagery to apply the text to our own life. Are the “enemies” actual persons or are they out of the physical realm? The line “The enemy has pursued my soul” suggests the latter.

We may ask ourselves, Who is the enemy? A crippling sense of guilt that prevents us from fully embracing God’s mercy? Destructive inner voices that insist we’re unworthy of God’s deep love? Psalm 143 is especially rich as a way into using a prayer text metaphorically rather than literally.

Penitence would be incomplete without confidence in God’s mercy. Despite the guilt that plagues him, the psalmist trusts in God’s merciful love (6). Though beset by ill health and the taunts of friend and foe, the psalmist has unshakeable confidence in the mercy of God who knows him through and through.

Psalm 130, “De profundis” (“Out of the depths”), used by the church as a prayer for the deceased, emphasizes unwavering trust in the Lord’s mercy and forgiveness.

Described here are just a hint of the treasures to be found in the penitential psalms. Explore them for yourselves to see what else you can discover.

Lenten practices, in order to bring about true conversion, ought to have elements that continue in our lives beyond Lent. Perhaps making the acquaintance of these psalms will provide material to deepen your spiritual life for every season of the year.

***

De Flon is an editor at Paulist Press and the author of “The Joy of Praying the Psalms.”

PREVIOUS: Journey with Jesus on scriptural stations of the cross

NEXT: Eight ways (at least) to pray during Lent

Share this story