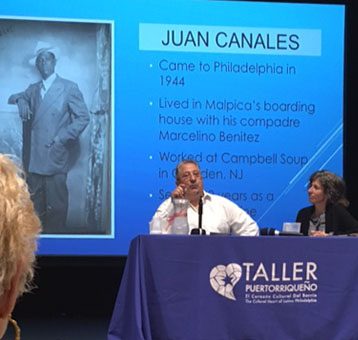

Victor Vazquez-Hernandez makes a point in his talk about his recent book, “Before the Wave: Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia, 1910-1945.” (Arlene Edmonds)

Puerto Ricans have been living in the Archdiocese of Philadelphia since the earliest part of the 20th century. After the Foraker Act of 1900 and a U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1917 granted Puerto Ricans U.S. citizenship, the mostly Catholic Puerto Ricans began to settle in South and North Philadelphia as well as center city.

Perhaps no one is more aware of this than Victor Vazquez-Hernandez, author of “Before the Wave: Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia, 1910-1945.” In doing his research, Vazquez-Hernandez said the Catholic Church’s records proved to be an invaluable source for understanding the history, culture and parish life of those early Puerto Rican city residents.

In particular the archives of the Vincentian order of priests, stored in Philadelphia’s Germantown section as well as in Rome, assisted him in finding where Puerto Ricans lived and worshiped.

[hotblock]

Vazquez-Hernandez can often be found at the “Meet the Author” and other special series at the nonprofit Taller Puertorriqueno, 2600 North Fifth Street in North Philadelphia. He has been to the community center on several occasions sharing the culture and life of Puerto Ricans in the Philadelphia area who arrived before World War II.

“Catholics do keep good records,” Vazquez-Hernandez said. “There are (Puerto Rican) marriage and baptismal records dating back to 1909.” The scholar stressed that Puerto Ricans who came to the city were not immigrants, because they were American citizens.

While some ethnic groups formed parishes reflecting their own language and customs, Puerto Ricans and other groups formed Catholic missions, not parishes, and therefore they do not appear among the official lists of parishes from during that era.

Participants at a talk by author Victor Vazquez-Hernandez at Taller Puertorriqueno learn about the history of Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia. (Arlene Edmonds)

Since they may not have had enough members to form a parish, smaller groups of Puerto Rican faithful met in church basements, according to Vasquez-Hernandez.

He said many of the later Spanish-speaking parishes came out of missions located in Old St. Mary’s Church in Old City. It was there that the foundation for the predominantly Puerto Rican Catholic community known as La Milagrosa (Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal) was laid. The mission congregation moved to 19th and Spring Garden streets in 1912 and remained there for about 100 years, according to Vazquez-Hernandez.

St. Katharine Drexel donated more than $1,000 and raised the rest of the money to purchase a house at the Spring Garden Street location. Homes in the North Philadelphia area a century ago cost less than $1,500, according to the scholar.

In the deed, St. Katharine insisted that if the “Spanish-speaking colored people” were ever excluded from worshiping at the site that the funds in the amount of the current market value at the time would have to be refunded to St. Katherine’s order, the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indian and Colored Peoples. The chapel was put up for sale by its owner, the Vincentians, in 2012.

“My father was buried at Milagrosa,” said Rafaela Colon of North Philadelphia. “For my father and many other Puerto Ricans that church was one of the most important parts of their life. That was considered their church home and the home of Puerto Ricans in the city for a very long time. Our roots go back far in Philadelphia.”

[hotblock2]

Though no longer at its original location, the La Milagrosa community has been celebrating Spanish language Masses at the Miraculous Medal Shrine in Germantown since 2015. The Masses are celebrated on the first Tuesday of every month.

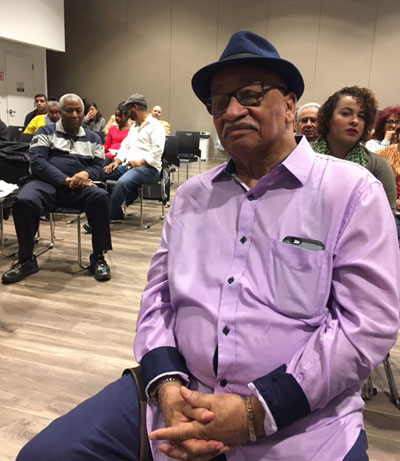

Among those who trace their origins to the Puerto Rican families who are highlighted in Vasquez-Hernandez’s book is the Juan Canales clan.

Canales relocated to Philadelphia from Puerto Rico to work at Campbell Soup Co. in Camden, N.J. His son, Vincent Canales, remains a faithful Catholic and sometimes sporting the suit and tie his father often wore to Mass in honor him.

Canales’ niece Ana A. Benitez said it was exciting to feature those Puerto Rican Catholics who are visibly of African heritage. She said many Americans think Puerto Ricans are undocumented or do not realize most Puerto Ricans are of African, Taino (indigenous Caribbean peoples) and Spanish descent. They come in all skin colors and features.

“People are always asking me, are you really Puerto Rican? I know (I am) because of this,” she said, pointing to the back of her hand.

Musician Jesse Bermudez, another relative of Canales, said that although many in the Puerto Rican community chose to attend Spanish-speaking churches, this does not mean they are clannish people.

He is quick to point out many live in mainstream communities and have married Catholics of other ancestry. Some have become blended so they may no longer speak with an accent and others no longer have Spanish last names.

A cultural strength that connected those early Puerto Rican Philadelphians to the city’s African American community was music, according to Bermudez. He said both communities brought their own musical heritages into the Mass through worship and when they performed in the community.

“Those of us who worked in music would perform with African Americans. There was always that connection there,” Bermudez said.

Participants at the session engage in a question-and-answer session with author Victor Vazquez-Hernandez.

PREVIOUS: The hardest talk: Racism in parishes

NEXT: Naming of new Allentown bishop is ‘moment of joy,’ archbishop says

We had a great Puerto Rican seminarian who died of a brain tumor. I prayed daily for him and Father Phil Jordan who is now a priest. I still pray to the Blessed Mother for Father Jordan. The Puerto Rican seminarian parents still live in Phila.