With more than 60 million deaths worldwide over its six years, World War II was easily the deadliest war in human history. The United States didn’t get into it until December 1941, and American deaths through battle and other causes were 413,000.

With more than 60 million deaths worldwide over its six years, World War II was easily the deadliest war in human history. The United States didn’t get into it until December 1941, and American deaths through battle and other causes were 413,000.

More than 11 million Americans served in the military during the war and very few would ever suggest it was a mistake. Liberty, justice and decency were at stake and everyone knew it.

Many, many histories and memoirs have been written and are still being written.

One such account has just surfaced, written by an ordinary Philadelphian, Harry J. Houldin, who never rose above the rank of Private First Class. Soon after returning from the European Theater he typed out a manuscript of a hundred pages or so on a German typewriter he’d liberated, and tucked it away in a trunk.

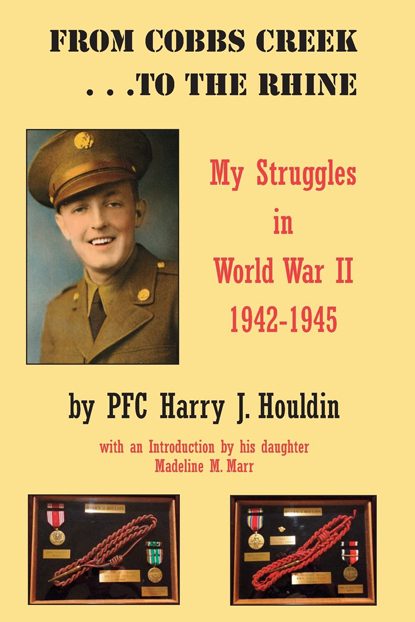

Harry died young and thanks to his daughter, Madeline Marr, it has finally been published under the title “From Cobbs Creek … to the Rhine: My Struggles in World War II, 1942-1945.”

He was a couple months shy of his 35th birthday in June 1942 when he had to report for induction at 32nd and Lancaster Avenue in Philadelphia. Although as edited the book says he enlisted, which would be voluntary, it is more likely that he was drafted, according to his written description.

[hotblock]

“To begin with I didn’t think they would take me as I was thirty-five years old, had a bad case of sinus and a potential hernia,” he wrote. “However, you usually get what you don’t want and, after a thorough examination, I was in with flying colors, much to my astonishment.”

That is the closest thing to a complaint in the entire book.

After training in Alabama and New York he was loaded onto a former banana boat and steamed for England as a jumping off point for North Africa and the Third Army headed by General George Patton.

Houldin was assigned to the First Division, First Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop, which in past generations was mounted cavalry but by this time mechanized with jeeps, armored cars and trucks.

What it mostly did was scouting and guarding the headquarters. Although his unit did not take part in infantry assaults, the task of Harry and his companions was nevertheless extremely dangerous as they sought out pockets of German troops, many times stumbling over mines laid by the retreating enemy, or found themselves ambushed or attacked from the air by German bombers or fighters.

During one particularly hazardous period he was driving truckloads of gasoline to fuel the tanks on the front lines in the face of blistering artillery shelling.

His outfit saw action in Africa all the way from Oran, the Kasserine Pass and Algiers. When that fighting was winding down it was on to Sicily for a relatively short campaign, although his unit suffered more casualties.

After Sicily it was a return to England where plans were underway for the invasion of Europe through France.

[tower]

It was here Harry’s old hernia kicked in with a vengeance, no doubt exacerbated by the huge amount of equipment he had to carry. He was in the hospital for an operation and rehab when D-Day came. His unit landed on Omaha Beach in Normandy the day after the first assault landing, and suffered a number of casualties.

By the time he returned to duty with his unit the fighting was 20 miles inland. Over the next several months it was a steady stream of skirmishes with more killed and wounded, and near misses for himself. He was active in the Battle of the Bulge in late 1944 and early 1945, and crossing the Rhine at Remagen Bridgehead in March 1945.

What is striking in his book is the absolute lack of personal animosity Houldin displays in his writing toward German soldiers and civilians when away from the battlefield. At one town the first thing he did was go to a barber shop an ask for a shave, never mind it was a straight razor. The barber was not the enemy.

Houldin could have been killed easily at another farmhouse when the German owner brought out a bottle of liquor and offered Houldin and his companion a drink. Not one to decline liquid hospitality under any circumstance, Houldin accepted but wisely said to the host, “Pour one for yourself,” and watched him drink it first.

The war wasn’t quite over as they went on through Germany and Czechoslovakia in mostly mopping up operations.

Hostilities in Europe officially ended on May 8, 1945, VE Day, the date German representatives signed the surrender document. But Harry was not rotated home and discharged until September.

For his service he earned seven battle stars and a host of medals. He never got a Purple Heart because he came home without a scratch. But then again the Honorable Service Lapel Button, which all honorably discharged vets got, featured a rather odd-shaped eagle and was irreverently nicknamed “The Ruptured Duck.” It seemed appropriate for a guy who got a hernia through his service.

After his discharge Harry wasted no time. He met Marie Veronica Glaser at a dance at the old Wagner Ballroom and within five months they were married at Nativity B.V.M. Church in Port Richmond and settled in Most Blessed Sacrament Parish in West Philly.

Harry took a truck-driving job at Gulf Oil and he and Marie had two kids; Madeline, who saw his memoir to completion, and Michael, who by the way is a former news editor of the former The Catholic Standard and Times.

Harry Houldin lived through a harrowing experience in World War II through Africa and Europe.

He was justly proud of his service and proud to have served under General George Patton. He died from cancer at the relatively young age of 55. Somewhere in Heaven he must be smiling to know his daughter has told his story. His memoir reinforces the judgment of commentator Tom Brokaw, who dubbed Harry and his fellow soldiers, sailors and marines, “The Greatest Generation.”

***

“From Cobbs Creek … to the Rhine” can be purchased in paperback for $9.99 through Amazon.com.

PREVIOUS: St. Thomas More alumni give $148K in Catholic high school aid

NEXT: Men, women with same-sex attraction take Courage at conference

Share this story