St. Peter Claver Church, which had served African American Catholic since 1892 at a time when they were unwelcome at other Catholic churches, will formally close effective April 8. (Photo by Sarah Webb)

The Archdiocese of Philadelphia has announced that effective April 8, St. Peter Claver Church — for generations the mother church for African American Catholics in Philadelphia — will formally close.

Archbishop Charles Chaput approved the relegation of the church building to profane but not sordid use. This designation under canon law means the building will close as a Roman Catholic church. (See the official canonical decree here.)

The formal request to close this former worship site originated with the archdiocesan Secretariat for Evangelization and was reviewed by the archdiocesan Council of Priests and presented to Archbishop Chaput, who after careful review of all supporting factors made the final decision.

[hotblock]

St. Peter Claver Parish, which was founded in 1886 and administered by the Holy Ghost (Spiritan) Fathers, was Philadelphia’s first designated African American parish. It officially closed in 1985.

Unlike other personal parishes, it was not founded to serve immigrants who arrived without English skills. Pure and simple it was founded because black Catholics in that era were not welcome in white parishes.

The church building has been declared historic, which may impact its future use, and it traces back further than St. Peter Claver Parish. The church was built circa 1842 as the Fourth Presbyterian Church of Philadelphia.

That congregation moved to West Philadelphia in the 1880s and the church was put up for sale for $20,000.

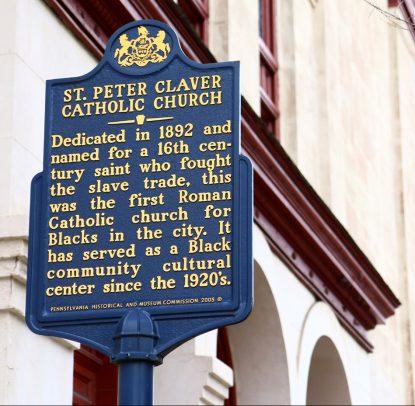

A historical marker at the church tells of St. Peter Claver’s significance for Black Catholics. (Sarah Webb)

Meanwhile the Black Catholic population in the city was growing. Among the earliest arrivals, according to one history, were refugees from turmoil in Santo Domingo. Others would come from such areas as Maryland, South Carolina or Louisiana, the former slave states that had a fair number of Catholics,

All of them could only worship at separate Masses in local churches.

The Notre Dame Sisters conducted a small school, and the Sisters of Providence, the nation’s first black congregation, also conducted a school for black children in Philadelphia for a time.

The future St. Katharine Drexel and her two sisters Elizabeth and Louise purchased a house to be a temporary chapel, which evolved into what would become St. Peter Claver Parish.

A big break came when Patrick Quinn, a former treasurer of the Beneficial Savings Fund Society, left in his will $5,000 “for the colored mission.” Enough funds came from other sources that the Fourth Presbyterian Church was purchased and renovated for Catholic worship.

Archbishop Patrick Ryan officiated at the Jan. 3, 1892 dedication while Father Augustus Tolton, the nation’s first black priest was present that evening for vespers. Father Tolton’s cause for sainthood is currently under way in the Catholic Church.

[tower]

In time, Philadelphia would have four designated Black Catholic parishes — St. Peter Claver, Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament, St. Catherine of Siena and St. Ignatius, each with a school conducted by Mother Katharine Drexel’s Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament.

All have closed except St. Ignatius of Loyola, which has absorbed the former Our Mother of Sorrows Parish and is no longer a Black Catholic personal parish.

The personal Black Catholic parishes were unintended victims of the civil rights movement. Now African American Catholics can and usually do attend the nearest church to them. Many parishes that once were entirely Caucasian now have an African American majority, at least in this generation, although neighborhoods constantly evolve.

St. Peter Claver was founded as an African American parish after the neighborhood changed from essentially Caucasian to African American and the original Presbyterian congregation relocated. In recent years the African American population in the area of 12th and Lombard streets has diminished.

After St. Peter Claver was suppressed as a parish in 1985, the rectory was occupied for a time by the Office for Black Catholics as the St. Peter Claver Center for Evangelization, with occasional Masses celebrated for a very small congregation in the former church.

The former school was used by archdiocesan Catholic Social Services as a residence for the Women of Hope program, which will now be moved elsewhere.

At this time, African American ministry is more centered in the parishes rather than at the diocesan offices, explained Franciscan Father Richard Owens, the director of the Office for Black Catholics.

Today a number of Philadelphia parishes have an African American majority, including St. Martin de Porres, St. Cyprian, St. Ignatius, St. Raymond and St. Malachy, but most parishes throughout the archdiocese have some African American members, Father Owens explained.

He points to a section of the new archdiocesan announcement that deals with the future and how a sale of the St. Peter Claver properties would affect ministry to Black Catholics as a whole.

[hotblock2]

It reads in part:

“It is envisioned that a sale of these properties by the archdiocese would generate funds dedicated to supporting ongoing ministry to Black Catholics.

“Recognizing the legacy and history of St. Peter Claver Church, the Office for Black Catholics supervised the movement of many sacred items from the church to active parishes in the archdiocese where African American Catholics currently worship. These items include the altar, baptismal font, statues and sacred vessels.

“As the St. Peter Claver Center for Evangelization served a great need and is now closed, the archdiocese is pleased to announce a new effort for the evangelization of African-Americans, the St. Peter Claver Evangelization Fund (SPCEF).

“The SPCEF will support parish-based programs that spread and strengthen the Catholic faith such as the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA) as well as programs for youth and young adults.

“The SPCEF will also be available to support programs of evangelization in Independence Mission Schools, Catholic elementary schools and high schools as well as colleges and universities serving African-American students. Parishes and schools will be able to apply for a grant to support such initiative.

“SPCEF will be administered and supervised by the Office for Black Catholics along with a board of laity and clergy serving in the African American community.”

The St. Peter Claver campus, consisting of the church, a former school and rectory, is located at 12th and Lombard streets in Philadelphia. (Sarah Webb)

Share this story