Every baptized Catholic is called, through the “priesthood of the laity,” to serve one’s brothers and sisters in the church and society. Priests as well as women and men religious, however, have by ordination or consecration special roles in the church.

Every baptized Catholic is called, through the “priesthood of the laity,” to serve one’s brothers and sisters in the church and society. Priests as well as women and men religious, however, have by ordination or consecration special roles in the church.

As their numbers in active ministry in the Archdiocese of Philadelphia have waned over the past 50 years, all the faithful face new challenges of discipleship now and in the future. No longer can one rely solely on Father or Sister to minister 24/7 in the community.

At this time, there are 451 diocesan priests in the archdiocese, of which 304 are on active assignment here, about 134 are retired and the balance of 13 are elsewhere, serving in Rome or the military, for example.

[hotblock]

There are also 280 priests of religious orders active or retired, and 2,230 religious sisters, active or retired, and 79 religious brothers active or retired.

Even though a number of the retired priests volunteer for weekend ministry, they are stretched thin.

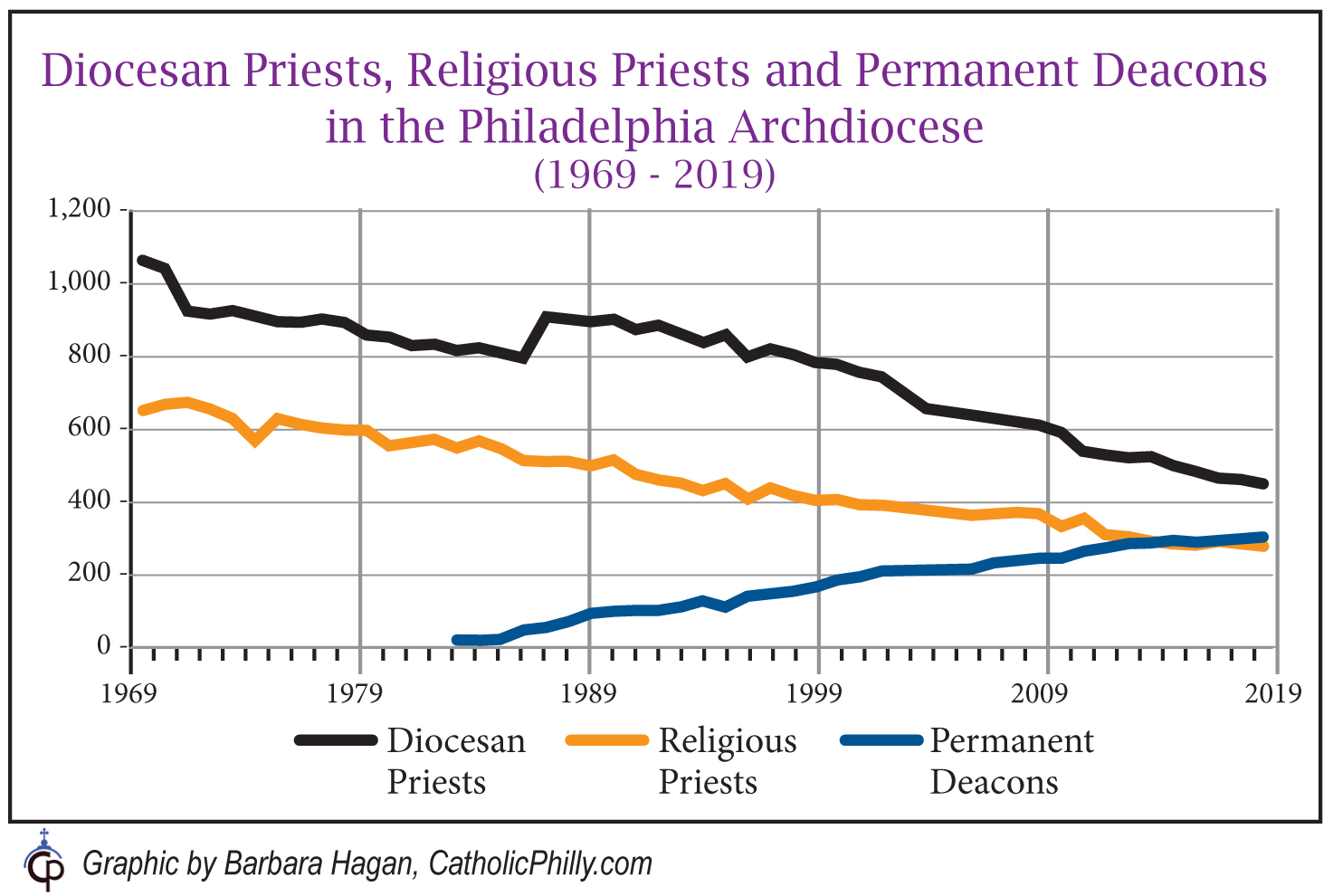

Contrast this to 1969, when there were in the archdiocese 1,086 diocesan priests active or retired (a 58% decline to present), 650 religious priests (down 57%), 6,622 women religious (66%) and 383 brothers (80%).

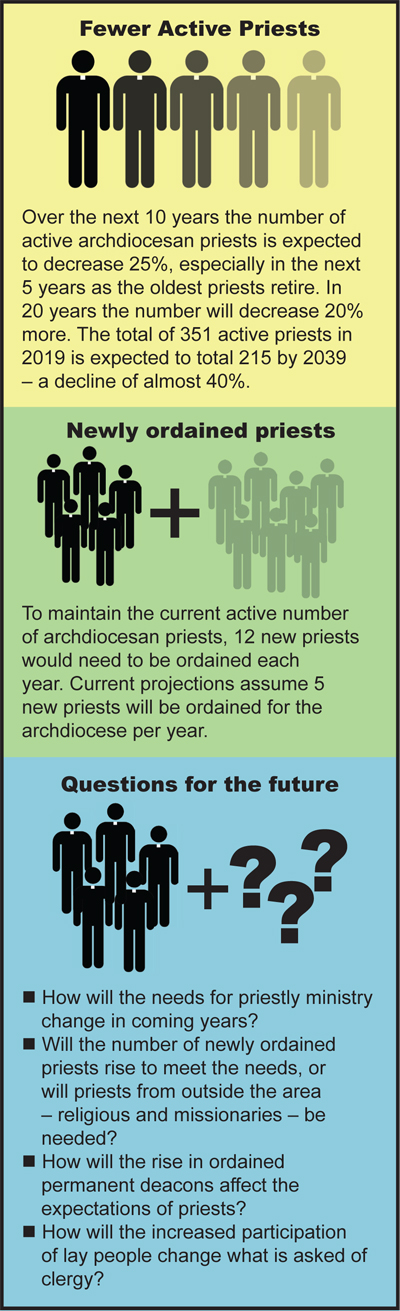

According to an estimate prepared by consulting firm AON Hewitt, the projected number of priests in active ministry will further shrink to 215 by 2039.

The figure presumes five new priests ordained for the archdiocese every year, based on the average of new ordinations here over the past seven years, and a normal rate of deaths and retirements.

As with the correlation of the clergy sex abuse scandal and Mass attendance in parishes of the archdiocese, so too the crisis has had an effect on the number of priests, with larger ordination declines during the years when it was most publicized.

Accusations of abuse have been ongoing, although most are from alleged actions more than 30 years ago.

(Graphic by Barbara Hagan, CatholicPhilly.com)

Msgr. Daniel Sullivan, the Philadelphia Archdiocese’s vicar for clergy, entered St. Charles Borromeo Seminary in 1968, when most of the priests who would be eventually accused of child molestation were already ordained. Even in that era, he had to undergo a psychological examination before being accepted. But preparation is much more in depth today, he said.

Now in the seminary and after ordination “there is much more stress on human formation. There is more openness in discussing problems. We are more aware of boundary violations that were never thought of before. Back then, no one would think there was anything wrong if a priest took kids to the shore. We are much more aware of things,” Msgr. Sullivan said.

The biggest mistake the archdiocese made when a priest was accused was to simply send him for psychiatric treatment and then return him to a parish assignment. “We thought they could be cured, but they couldn’t,” Msgr. Sullivan said. “I do think we have it in hand now.”

[tower]

Another factor in the decline of priestly vocations may be the decline in the number of students at Catholic schools exposed to religious instruction on a daily basis. Since 1969 in the archdiocese, parish school enrollment has declined 77% and high school enrollment is down 70%.

Although the Clergy Office estimates five new priests a year for the future, Msgr. Sullivan points to a hopeful sign in the number of men entering the seminary for the first time. “We had 20 men enter (for Philadelphia),” he said. “I think it was half post–high school and half post-college.”

Generally, about half the men who enter the seminary will likely discern that the priesthood is not their vocation and leave. But if this year’s number holds, Philadelphia could be looking at having 10, rather than five, of these men ultimately ordained.

While the clergy abuse scandal may account for part of the decline in the number of men entering the seminary, it cannot explain the even greater decline in vocations to the congregations for women.

There was no major scandal among women religious in this country, so the reason may have more to do with the changing roles available to women and changing societal norms over the past half-century.

At this point, there are 2,227 sisters in the Philadelphia Archdiocese, of which 881 are retired, according to Sister Gabrielle Marie Braccio, R.S.M., the archdiocesan delegate for consecrated life.

This contrasts to 6,622 women religious in 1969. They minister in various places including hospitals, parishes and schools “doing what the church asks us to do,” she said.

The problem is that many of the congregations do not have postulants or novices in formation. However, there are some congregations that seem to be doing quite well, including such newer orders as the Sisters of Life and Sister Gabrielle’s own Sisters of Mercy of Alma, Michigan, founded in 1973.

As with most of the congregations that seem to be growing, the latter order is traditional in both garb and outlook. “We have 108 members; a quarter are in formation,” Sister Gabrielle said.

But on the whole for religious life, “I think the numbers will come back” she said. “If we trust in the Lord, even if we are not as large, we will be fine.”

There is a third group of religious that is actually thriving: permanent deacons, who are the second order of ordained clergy. Founded by the bishops of the early church, the ministry of the diaconate was established to support the church through service.

For many centuries, the diaconate was relegated to a final step before ordination to the priesthood. In 1967, when the number of priest ordinations was diminishing worldwide, the permanent diaconate was restored to a distinct ministry of service.

Permanent deacons, who are members of the clergy, are mature men who perform many of the duties of a priest, although they cannot celebrate Mass, hear confessions or anoint the sick.

It is a part-time ministry but has a vital role in the modern church. Philadelphia’s first class of 24 permanent deacons was ordained in 1983, and their numbers have grown to the present 304.

This ministry has proved to be highly successful, according to Deacon Michael Pascarella, who heads the Department of the Diaconate for the archdiocese.

More recently, the number of men applying for the deacon program has diminished but “we are seeing younger men,” Deacon Pascarella said.

[hotblock2]

Finally, there are the many lay workers and volunteers who help keep the church running. They were not as prominent back in the days when there were more than a thousand priests in the archdiocese. If you rang the rectory doorbell back then, it would be a priest who answered and took care of your request.

In fact, at a time when the archdiocese was ordaining scores of priests every year, the real issue was where to put them. In 1936 when St. Thomas More High School opened, the founding faculty appointed by Cardinal Dennis Dougherty were young priests straight out of St. Charles Borromeo Seminary, who undertook their teaching duties without formal certification in a specific subject.

Although priest to laity ratios were not much of a concern then, the previous boom in ordinations raises the question of whether the archdiocese ever really needed more than a thousand priests at a given time. Certainly the church could use more priests than we have today, but in this one church of bishops, priests, deacons, women religious, brothers and ordinary laity, all are equally important for working together to build God’s kingdom.

PREVIOUS: Catholic school teachers need not burn out, become cynical, says author

NEXT: Amid conflict and pessimism, St. Rita shrine offers ‘impossible hope’

Share this story