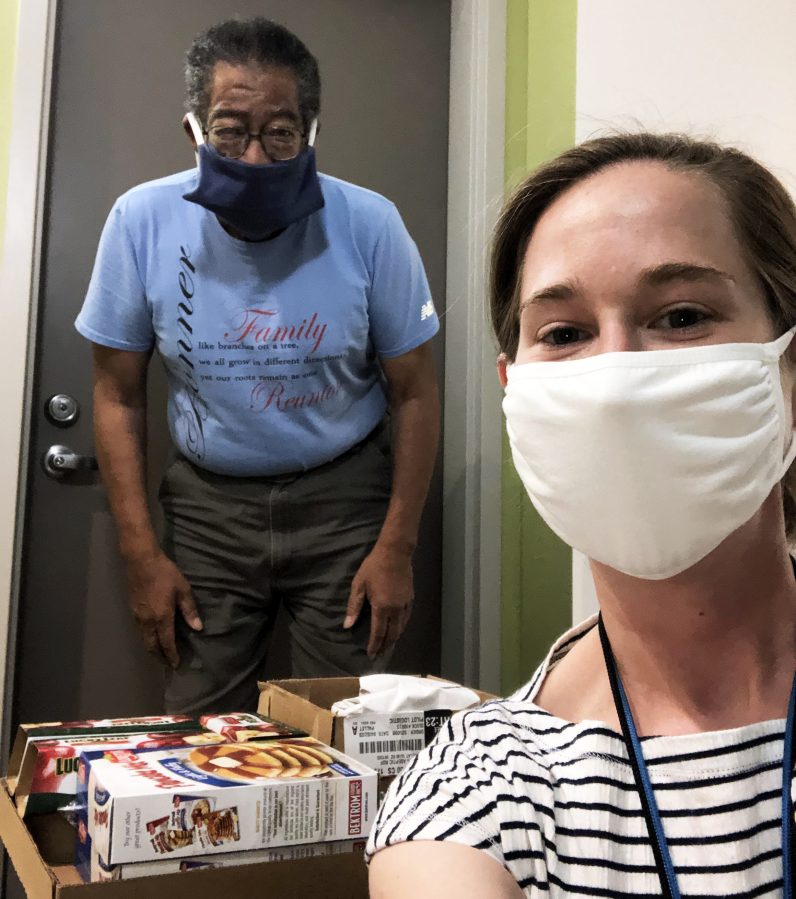

Social worker Caroline Morgan distributes food to William Bonner, a resident of St. John Neumann Place II in South Philadelphia, May 28. Morgan, director of social services at the archdiocesan senior housing complex, created a mobile food pantry to serve clients made food insecure by the COVID-19 pandemic. (Photo courtesy of Caroline Morgan / Suzanne O’Grady Laurito)

Even as COVID-19 restrictions are lifting, archdiocesan outreaches are responding to increased requests for assistance among area seniors.

“We’re seeing more older adults approach us for food, financial aid and emotional support,” said Heather Huot, executive director of archdiocesan Catholic Housing and Community Services (CHCS).

The agency provides a continuum of care to the region’s older adults through activity centers, in-home support and affordable housing.

Throughout the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have emphasized that seniors are at greater risk of both contracting and dying from the virus.

Comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension, age-related chronic inflammation (or “inflammaging”), and greater exposure to the virus through public transportation and congregate care have all compounded the impact of COVID on older adults.

Socially distanced and depressed

That vulnerability extends beyond the physical, as many older adults have experienced mental distress due to weeks of social isolation under stay-at-home orders.

“The longer this goes on, the more we’re finding people are getting anxious, depressed, lonely,” said Karen Becker, CHCS’s director of senior center services. “More and more, we’re seeing effects on their mental health.”

As a result, Becker and her team have stepped up phone calls to clients, some of whom are on a CHCS “watch list.”

[hotblock]

“We call them a few times a week,” said Becker. “All of my staff can tell you it’s usually not a quick call.”

“Most want to stay on the phone quite some time,” she said, since the interactions are often the only interpersonal contact seniors have for days or even weeks on end.

Although online communications became the norm during the pandemic, many seniors lack high-speed internet and updated devices, excluding them from staying at least digitally connected to family and friends.

A woman receives a set of free meals from Nativity B.V.M. Place in Philadelphia, May 27. One of four senior centers operated by archdiocesan Catholic Housing and Community Services, the site has seen an increase in requests for food assistance among area seniors throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. (Photo courtesy of Karen Becker / Jennifer Scornaienchi)

Becker said she and her team monitor clients for signs of depression while providing lists of mental health resources. The feedback from the check-in calls has been overwhelmingly positive, she said.

“They’re grateful to have somebody know whether they’re OK or not,” she said, with many clients concerned about family members who are keeping their distance to protect elderly loved ones.

“It’s heartbreaking,” said Becker. “They can’t see their children, they can’t see their grandchildren.”

Giving seniors a sense of hope is essential at this time, said CHCS assistant director Suzanne O’Grady Laurito.

“We’re asking them questions about their background, their spouses and how they met,” she said. “Focusing on beautiful things transports them to a happier time, and gets them out of this sadness and drudgery.”

George Harrison, a Norristown-area CHCS client, wrote to thank the agency for its “kind and caring” support for seniors.

“It is such a comfort to know … that there are people out there like you who reach out with concern for the elderly citizens of our parish,” he said.

Harrison also said that prior to the CHCS call, he and his wife “had never had a reason to contact (CHCS) and use (its) wonderful services.”

A rise in first-time clients

In fact, a number of the agency’s new clients — particularly those between ages 60 and 65 – have never accessed senior aid.

“Many were working before (the pandemic),” said Becker, noting that such income was vital in supplementing Social Security and pension checks.

Applications to CHCS for financial assistance “have exploded,” she said, with “rental, mortgage, food and medication copays” driving the demand.

Food insecurity among older adults has been exacerbated by the pandemic, and cupboards in many seniors’ kitchens have become bare over the past several weeks.

Huot said that one new CHCS client, a 73-year-old woman, began to cry when she was assured the agency could deliver weekly meals (including cheese and vegetables) to her home.

The woman – who suffered from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and had difficulty walking — was “down to a couple of TV dinners and a few cans of soup,” said Huot, and had no one to assist her with food shopping.

Laurito said that several partners in hunger relief — such as archdiocesan Nutritional Development Services, Caring for Friends and Project Isaiah — have been “fabulous” in bolstering CHCS’s reach.

Project Isaiah, which sources meals from airline caterer Gate Gourmet, has been providing airplane snacks as part of CHCS meals.

“It’s such a little thing, but our (senior housing) residents are delighted,” she said. “It’s unexpected, but it means so much to them.”

CHCS staffer Linda Rothwein said that a client had called her office “thrilled” over a box of fresh fruit delivered to his house. Becker said her team was rounding out such packages with vegetables, eggs and milk.

She added that CHCS staff “are honored to do (such) worthy work.”

“This is really concrete assistance that people can see and feel, even if it’s just a simple wellness check,” she said. “There’s gratitude and affirmation for it.”

PREVIOUS: At first public Masses in archdiocese, a grateful spirit of joy

NEXT: Social worker guides parents through pandemic to brighter future

Share this story