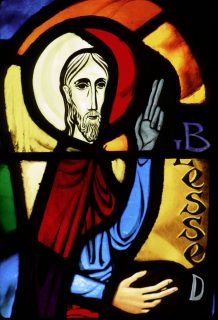

A church window depicts Jesus giving his Sermon on the Mount, which begins with the beatitudes. Jesus singled out persecuted people in his beatitudes, along with people who were poor, hungry or meek and humble (Mt 5:3-13; Lk 6:20-23). (CNS photo/Crosiers)

Why do bad things happen to good people? I wonder how many victims of persecution across the ages asked themselves some version of that now-famous question.

Jesus singled out persecuted people in his beatitudes, along with people who were poor, hungry, or meek and humble (Mt 5:3-13; Lk 6:20-23). The crowd that first heard the beatitudes in Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount surely included many suffering the effects of their world’s oppression.

Notably, Jesus called them “blessed,” a term synonymous with calling them “holy,” Pope Francis observed in “Rejoice and Be Glad” (“Gaudete et Exsultate”), his 2018 apostolic exhortation on holiness today.

That papal document includes an extended discussion of the beatitudes, driving home a message that the beatitudes “are in no way trite or undemanding” (No. 65); they should be allowed “to unsettle us” (No. 66).

In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus says, “Blessed are they who are persecuted for the sake of righteousness” — persecuted for following God’s will, according to a note in the New American Bible. “Theirs is the kingdom of heaven” this beatitude adds (Mt 5:10).

It must have been wonderful for oppressed people to hear. But did the powers that be in their world leave them to fear for the future and their families’ well-being?

It may be safe to assume that many in the crowd felt oppressed. What seems unsafe to assume is that God is absent from persecuted people’s lives or unconcerned with their plight.

Jesus’ “tenderness for the lowly and the poor” is apparent in the beatitudes, the Jerusalem Bible notes in discussing Luke’s Gospel.

[hotblock]

Persecuted people today suffer from indifferent, inhospitable and cruel treatment. Some persecuted people have been driven from their homelands.

Are they haunted by the tragedy of warfare that forced them away from their extended families’ support? Are they unable to make sense of the demonization they now experience due to their religion, race, ethnicity or customs?

Words are a likely culprit when it comes to creating an atmosphere that makes persecution acceptable in society or, at least, enables many to overlook it. I am talking about words that brand people in negative ways and serve to isolate them from the care and concern of so many others.

The negative power of words is a point of interest for Christians. Their faith that Christ is God’s incarnate word on earth tells them that the negative power in human words is not their only power. Human words can reflect God’s own word in highly positive ways.

In his 2021 homily for the Christmas Eve Mass at St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota, Benedictine Abbot John Klassen exclaimed, “The Word was made flesh; the Word was made love!”

But countless times in human history words worked fiercely against the broad range of love’s purposes. Words were exploited to cast a shadow over the dignity of human beings.

The 20th-century Holocaust at the time of World War II under Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany killed some 6 million Jews. It remains a never-to-be forgotten instance of human persecution’s horrors.

Cardinal Blase J. Cupich of Chicago has examined the role words played at that time in establishing an atmosphere designed to obscure the dignity of Jews and some others from the public’s view.

“It all began with words. Words that called people ‘other,’ that targeted people as worthy of fear” or as a threat to a nation’s greatness, the cardinal observed in a 2019 commentary in the Chicago Catholic newspaper.

His remarks related directly to “our Jewish brothers and sisters.” But Cardinal Cupich added:

“As Jonathan Sacks, former chief rabbi of the United Kingdom, reminds us, ‘The hate that begins with Jews never ends with Jews.”’ Intolerance also must be shown, said the cardinal, “for hate speech that targets others who are easily marginalized in society.”

Words can wreak tremendous harm. But words also are able to bring human dignity into the light. Isn’t that what Jesus’ beatitudes intended?

Jesus pointedly advised a crowd that “you who are poor” are blessed, as are “you when people hate you” (Lk 6:20-22).

Pope Francis advised in “Rejoice and Be Glad” that while Jesus’ words in the beatitudes “may strike us as poetic, they clearly run counter to the way things are usually done in our world,” and “we can only practice them if the Holy Spirit … frees us from our weakness, our selfishness, our complacency and our pride” (No. 65).

But “practice them”? The beatitudes do not in themselves constitute a set of direct instructions. Still, no one involved in persecuting others will feel comforted by the beatitudes.

“Persecutions are not a reality of the past,” Pope Francis noted. “Today too we experience them, whether by the shedding of blood, as is the case with so many contemporary martyrs, or by more subtle means, by slander and lies” (No. 94).

For Pope Francis “the beatitudes are like a Christian’s identity card.” In them “we find a portrait of the Master that we are called to reflect in our daily lives” (No. 63).

***

Gibson served on Catholic News Service’s editorial staff for 37 years.

Share this story