People have sometimes called me the “whitest” person they know.

It’s a weird thing to hear. I suppose they mean my pale skin and light eyes; my Midwestern look and name; and my suburban Catholic vibe.

All true … and yet, not.

Because every one of those attributes comes from a conscious decision made more than century ago to tear three little boys from their black mother in Louisiana so they and their future families could “pass” as white.

That would be my great-grandmother Olivia.

It is her spirit I bring to our parish and Archdiocesan efforts to fight the evil of racism – in our world and in our Church.

One Drop

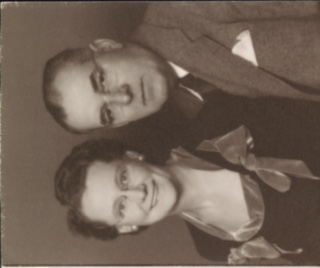

My paternal grandparents were Etta and Michele “Mike” Chollet. In hindsight, Mike’s mixed-race background is apparent against the whiter-skinned Etta.

Race was a secret our family buried for generations. Growing up, we knew that my Dad had never met his grandmother, though she lived until he was an adult. We knew that my grandfather and his brothers had been taken from their mom and raised with a distant cousin they called Sis. But we never knew why. Was it addiction? Prostitution? Destitution?

It was my brother’s digging, confirmed by DNA testing, that finally unearthed the truth when we were all adults. Olivia was unmarried, close descendant of slaves, living in the Deep South. This was literally Klan Country, home of future Imperial Wizard David Duke.

Whatever skin tone their mixed race produced, these boys would have been considered Black under the infamous “hypodescent” or “One Drop” legal principle, which reduced one’s status to the “lowest” ethnicity in their racial mix. (For the record, “One Drop” laws existed until I was 8 years old.)

Who knows what calculations went into the decision to break up and lie about the family … or who even made that decision? Maybe – unlikely, but maybe – Olivia herself felt that her boys would have a better future that would overcome the trauma of their present.

After all, “passing” was a desperately high-stakes gamble, a lifelong deprivation of identity, family, friends and home that one would accept only because the alternative — life as a person of color in post-Civil War America – was even worse.

So there is much I do not know. But I do know that that long-ago decision changed everything – for my family and for me. Whom I could marry. If I could vote. Where I could live, work, attend school, buy a home.

Uneasy Inheritance

My family’s story is hardly unique. Hundreds of thousands of African Americans are believed to have passed as white in that era.

But the revelation, and all the what-ifs it carries, changed my identity in a way that is difficult to unpack and uncomfortable to wear.

Because of the decision to make me white, I’ve never had to worry that my sons would be stopped by police for no reason, followed by store security, or avoided on the street. Their hoodies and baseball caps were always taken as signs of team spirit, not criminal intent. I’ve never been denied a job, a loan or housing based on race. I’ve never had an “ethnic” name that sent my resume into the trash.

Olivia’s loss was my ticket to life in the mainstream. It is a complex, unearned inheritance that never rests easy.

Nor should it. All white people share these privileges – and to whom much is given, much is expected, as Jesus tells us in the Gospel of Luke.

So when people ask why a white suburban parish and our Archdiocese are working against racism, and why I take the fight personally, I’m caught off guard. This should be everyone’s fight – especially those white Catholics who have the luxury to ask the question.

Whatever skin you are in – or think you are in — we are all created in God’s image. That makes racism an attack on the presence of God within each of us.

Standing Together

The Joint Catholic Ministry for Racial Healing, a partnership of St. John Chrysostom Parish in Wallingford and St. Martin de Porres Parish in North Philadelphia, is entering our third year. The ministry was established after the parishes co-hosted a Zoom Town Hall in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd.

Our group didn’t have a plan, and we are still feeling our way, but we deeply felt the need to organize a sustained response to the sin of racism in our communities. Since then, we have been meeting and engaging in dialogue, prayer and activities.

We had hoped that other parishes might also pair up and follow us. They haven’t yet, but we continue to reach out, to help identify and connect any area Catholics who support racial healing. I am also honored to serve on the Archbishop’s Commission on Racial Healing, established in 2021 and led by Fr. Stephen Thorne.

My committee’s efforts focus on change at the parish level – in the pews, where change must begin.

Our ministry gathered twice during Lent – once at each parish — to pray the Stations of the Cross for Overcoming Racism, written by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Each session included an open invitation for participants to join us for hospitality and fellowship afterwards. This brought in new people, new conversations, new energy, and new hands and hearts for our mission.

For the solution to racism – to most problems, I believe – begins with prayer and encounter. And that is because racism isn’t just a secular issue. It is a Catholic issue that demands a Catholic response.

The Body of Christ

Our Black Catholic brothers and sisters are leaving the Catholic Church at even higher rates than whites because they feel unwelcome and their concerns disregarded. We are the Body of Christ. Whatever divides us is also ours to mend.

Racism wounds both body and soul. That makes it a pro-life issue, as Pope Francis has noted. We cannot accept exclusion “in any form and yet claim to defend the sacredness of every human life,” the Holy Father said in 2020.

The U.S. Bishops have been writing against racism since 1958, most recently in their 2018 pastoral letter, Open Wide Our Hearts.

Even in post-Obama America, the Bishops note, “racism still profoundly affects our culture, and it has no place in the Christian heart. … People are still being harmed, so action is still needed.”

Children of Light

Both our Joint Parish Ministry and the Archbishop’s Commission are interracial groups, where discussion can feel challenging and awkward; the mission, overwhelming; and progress, elusive.

This is, after all, a sin as old and vast as mankind. What can a handful of volunteers do about it? Like Merton, I often think: My Lord God, I have no idea where we are going. I do not see the road ahead of us.

And yet, the very existence of these ministries brings hope. Their presence calls out evil and provides space and structure for witness, encounter, prayer and action. The Archbishop’s Commission on Racial Healing is only the second commission created by Archbishop Pérez. That is significant.

So, like Merton, we trust that our efforts are pleasing to God and, from there, just do our best. For if you are not part of the solution, you are part of the problem.

As our ministries strive to progress, I often return to a prayer by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that embodies both my frustration and my hope.

We are not satisfied with the world as we have found it.

It is too little the kingdom of God as yet.

Grant us the privilege of a part in its regeneration.

We are looking for a new earth in which dwells righteousness.

It is our prayer that we may be children of light,

the kind of people for whose coming and ministry the world is waiting.

For whether we succeed or fail, we all owe it to Olivia to keep trying.

***

Mary E. Chollet is the Director of Ministry and Communications at St. John Chrysostom Parish in Wallingford, Delaware County and a member of the Archbishop’s Commission on Racial Healing. Mary can be reached at mchollet@sjcparish.org.

Share this story