Parish anniversaries are always worth celebrating. A 250th anniversary is awesome — think about it, that’s older than the United States itself.

Old St. Mary’s in Philadelphia, where Archbishop Chaput will celebrate a quarter millennium anniversary Mass on May 26, traces back to 1763. St. Mary Chapel, established by Jesuit Father Robert Harding, was really an offshoot of Old St. Joseph’s which was established in 1733. In fact the chapel was built on a section of the land purchased by the St. Joseph congregation for a graveyard.

At that time Catholic houses of worship were technically illegal in most of the British Empire, but Catholics were generally left alone provided they didn’t make waves. This was especially so in Philadelphia where Quaker tolerance held sway.

[hotblock]

Like St. Joseph’s, St. Mary’s as originally built deliberately looked very much like an ordinary house from the exterior, although it was much larger than St. Joseph’s and almost immediately became the venue for Sunday worship by Philadelphia Catholics.

The early congregation, with 222 families, was mostly Irish but with 30 German and 15 French. Some of the more distinguished early members were George Meade, great-grandfather to Civil War General George Gordon Meade, the victor at Gettysburg; Revolutionary War naval hero Commodore John Barry; Thomas Fitzsimmons, a signer of the Constitution; and Matthew Carey, a leading publisher in the Federalist era.

The chapel was not supported by collections; that was done by people paying for pews, a system that remained in effect almost into the 20th century. The better the pew the higher the rent — George Meade paid 40 pounds per annum during the colonial era and in 1857 the Pleasanton family paid $30 for a center aisle pew, both substantial sums for their times.

Through St. Mary’s, Catholicism received some recognition from the Philadelphia establishment during the Revolutionary War because Catholic support was needed for the cause and also to curry favor with France, our Catholic ally.

George Washington attended a Mass on Oct. 9, 1774 while the First Continental Congress was meeting, as did John Adams, a New England bigot if there ever was one. In a letter home to Abigail, he described the beauty of the chapel and the liturgy but couldn’t resist adding, “I wonder how Luther ever broke the spell.”

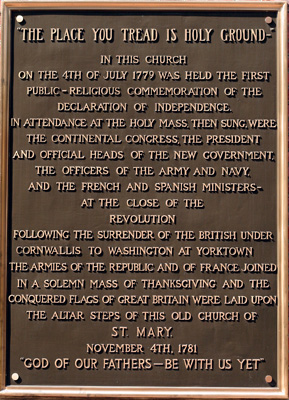

The Continental Congress attended four services at St. Mary to mark national milestones, and George Washington made a return visit in 1787.

The Continental Congress attended four services at St. Mary to mark national milestones, and George Washington made a return visit in 1787.

In 1793 Philadelphia was hit by the greatest disaster in its history before or since and St. Mary was not exempt. In the summer of that year the city experienced a yellow fever epidemic on a scale that is almost unimaginable.

An estimated 5,000 people died, a real disaster for a city of only 45,000 and the death toll would have been higher had not many fled the city to escape the pestilence. While some clergy also left, the priests at St. Mary remained to tend to the people.

For an idea of the effect of the epidemic on the parish, St. Mary Cemetery saw 63 burials for the first half of the year; the second half saw approximately 300, mostly in September and October. This was a huge number for a relatively small congregation. Try to imagine what it would be like for your parish to average five funerals a day every single day.

Later, at the order of the city, for sanitary reasons many tons of dirt were brought in to cover the cemetery because so many of the hastily dug graves were dangerously shallow.

In 1810 the church was substantially enlarged and that same year Philadelphia became a diocese. With the arrival of Bishop Michael Egan St. Mary became the de facto Cathedral and remained so until St. John the Evangelist superseded it in the late 1830s.

It was an honor but not an easy transition. Prior to this, without a bishop to appoint pastors, if there was a vacancy the lay trustees who were elected by the pew holders sometimes had to hire a priest or priests as well as pay their salary and all the other bills. It was not always possible to properly vet an immigrant priest for suitability.

This worked well with Protestant congregations but was not in keeping with Catholic canon law. When the bishops tried to assert control, the trustees resisted, reasoning the laity built the church and supplied all the upkeep.

In St. Mary’s case, the lay position was especially undermined through their unfortunate choice of pastor. Father William Hogan was a charismatic speaker but of questionable morals and orthodoxy, a man the bishop could not accept.

In St. Mary’s case, the lay position was especially undermined through their unfortunate choice of pastor. Father William Hogan was a charismatic speaker but of questionable morals and orthodoxy, a man the bishop could not accept.

Over the next two decades there constant flare-ups – street brawls, Bishop Henry Conwell locked out of the church, the excommunication of Hogan. It was only after the arrival of the very capable Bishop Francis Patrick Kenrick, first as coadjutor and ultimately third bishop of Philadelphia that the matter was settled. In 1831 Bishop Kenrick placed St. Mary under interdict with all services at the church forbidden. After a month or so the trustees capitulated and tranquility was finally restored, at least at St. Mary.

In 1832 St. Mary became the site of Philadelphia’s first-ever diocesan synod.

St. Mary was unharmed in the anti-Catholic riots in 1844. The truth is, although there were anti-Catholic feelings in all classes, the rioters were mostly Protestant and Catholic Irish immigrants who brought their mutual animosity with them to America.

The Protestant gentry of Philadelphia were appalled by what they were seeing and Protestant volunteers guarded St. Mary at times of flashpoint.

An interesting change was made in 1886, when the church was virtually turned around front to back, with the main entrance on Fourth Street rather than an inconspicuous courtyard.

Over the 250 years of the parish’s existence the Society Hill neighborhood surrounding St. Mary has seen many changes. Ever since the rebirth of the Society Hill section in the 1950s the neighborhood has been on the upswing.

Fred Ottaviano has lived in the vicinity for more than seven decades, first at Old St. Joseph’s and then when boundaries changed, at St. Mary’s. He well remembers it as a working-class Catholic neighborhood, complete with factories and Philadelphia’s fruit and vegetables distribution area along Dock Street until the city relocated the industry.

Houses were cheap and renters might have an apartment for as low as $20 a month. With planned redevelopment many of those who owned their homes sold them for a profit and moved to other neighborhoods, as did the renters. Ottaviano’s family owned several properties and sold some and used the proceeds to refurbish the others, and he has remained.

In the old days, he said, “the Church was the nucleus of the neighborhood. We had May processions and a lot of other activities,” he said. “There was a lot of cohesion in the parish.”

Ottaviano has seen pastors come and go, and most of them were quite effective and admired by the people. Now Msgr. Paul DiGirolamo is pastor and “he is a great guy, he brought a lot of life to the parish.”

Under the watch of Msgr. DiGirolamo Old St. Mary’s has had a bit of a revival itself, more so than neighborhood changes would account for.

In 2011 weekend Mass attendance averaged 293, which sounds modest until you realize that is double what the attendance was just three years earlier. Part of the secret, Msgr. DiGirolamo believes, is just being there for the people and for the parish to try to accommodate the people rather than the other way around.

In 2011 weekend Mass attendance averaged 293, which sounds modest until you realize that is double what the attendance was just three years earlier. Part of the secret, Msgr. DiGirolamo believes, is just being there for the people and for the parish to try to accommodate the people rather than the other way around.

The nature of the neighborhood is such that a good number of the families are renters and typically most of the people in the church on Sunday are in their 20s or 30s. Probably for that reason baptisms outnumber funerals four to one.

Because St. Mary’s is near the downtown hotels it is also a popular wedding venue, especially for couples who may be recent college graduates without ties to a local parish.

Weekday Masses are also well attended especially by those in town for work or shopping. Weekday Masses and special Masses are usually held at Holy Trinity, which was America’s first ethnic and first German parish, but is now a chapel for St. Mary, according to Msgr. DiGirolamo.

St. Mary’s School, which is now a regional school, remains viable partly because it is a practical solution for parents who work in the city but live elsewhere. They can drop the children off in the morning and pick them up on their way home from work.

Margaret Carroll has been a parishioner at St. Mary since 1969. While she loves the colonial character of the buildings that has been so carefully preserved, for her the greatest thing is the more recent influx of young people.

“It’s nice to see young people in the church,” she said. “St. Mary will survive and be loved by new parishioners.”

One of the greatest attributes of St. Mary’s is excellent music, according to Arthur Etchells, who moved into St. Mary 35 years ago when the neighborhood renaissance was already under way.

“All of the pastors have been conscious of the music program, and the organ and singers are integral to the parish,” he said.

The parish, in an area that is relatively prosperous, is very socially conscious as it helps poorer parishes and has an excellent food program, Etchells noted.

But again the biggest change in his time is the increased attendance. “When I first came the church was practically empty, you weren’t close enough to someone else to shake hands,” he said.

“Father Paul especially,” he said, has made the church welcoming, “always out front talking to the people and to the kids, making it very welcoming.”

***

Lou Baldwin is a freelance writer and a member of St. Leo Parish, Philadelphia.

PREVIOUS: At memorial Mass on his birthday, Bishop McFadden remembered in Cathedral he loved

NEXT: Rosary gave courage to soldier who recalls one of WWII’s last European battles

Share this story