Philadelphia Ukrainian Archbishop Stefan Soroka speaks at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Philadelphia, site of a March 16 prayer service for peace in Ukraine where he was joined by Archbishop Charles Chaput and Archbishop Antony, Metropolitan of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in the United States. (Courtesy of The Way/Ukrainian Archeparchy of Philadelphia)

Three archbishops — Roman Catholic, Ukrainian Catholic and Ukrainian Orthodox — joined together in prayers for peace at Philadelphia’s Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception on Sunday, March 16.

This was not unusual, at least for the United States, according to Archbishop Stefan Soroka, who is Metropolitan Archbishop of the Archeparchy (Archdiocese) of Philadelphia and the leader of Ukrainian Catholics in the United States.

He was joined that day by Archbishop Charles J. Chaput, archbishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Philadelphia and by Archbishop Antony, Metropolitan of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in the United States as well as a congregation of 500 mostly Ukrainian-Americans. (See a related story here.)

The prayers were in the wake of the overthrow of the pro-Russian government in Ukraine and the subsequent secession of Crimea from Ukraine and its annexation by Russia. Crimea, a peninsula in south Ukraine, hosts a heavily ethnic Russian population.

[hotblock]

The annexation has been widely condemned by most world leaders amid fears that Russia may attempt to annex other areas of Ukraine that have ethnic Russian populations.

“We offer in America something that I know they wonder about (in Ukraine),” Archbishop Soroka said in a March 24 interview with CatholicPhilly.com. “Our Ukrainian Catholic Church and our Ukrainian Orthodox Church here in America have been meeting for years. We meet every year for two or three days to discuss issues of concern. Our focus is not trying to resolve our differences but to understand one another. The more we come together, the more we realize how little difference there really is.

“When we meet, the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church in Ukraine are champing at the bit for our press release even before it is out. We are an example to them how different churches can come together.”

As a matter of fact, Ukrainian Catholics in the U.S. willingly meet and pray with all denominations, Christian and non-Christian, something that is less likely to happen in Ukraine and Russia, according to Archbishop Soroka.

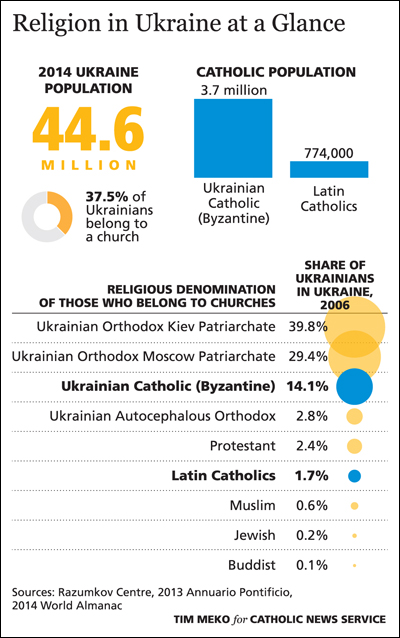

In Ukraine the majority religion is Orthodox, which by one estimate (Britannica 2014 Year Book) is composed of Ukrainian Orthodox at 19 percent, Russian Orthodox (Ukrainian Church of the Moscow Patriarchy) 9 percent and other Orthodox or unaffiliated Orthodox at 16 percent.

In Ukraine the majority religion is Orthodox, which by one estimate (Britannica 2014 Year Book) is composed of Ukrainian Orthodox at 19 percent, Russian Orthodox (Ukrainian Church of the Moscow Patriarchy) 9 percent and other Orthodox or unaffiliated Orthodox at 16 percent.

About 6 percent are Ukrainian (Greek) Catholics and about 2 percent are Roman (Latin) Catholics.

Probably as a result of harsh religious persecution under seven decades of communism, about 42 percent of the people are unchurched.

If there seems to be a larger number of Catholic Ukrainians in America than these figures would suggest, there is a reason, according to Archbishop Soroka, who relates the experience of his own family.

Most Catholics in Ukraine live near the western border near Poland, in an area that was occupied by the Nazis during World War II. Many of the people were taken captive and sent to Austria and Germany to slave labor camps. This was the experience of Archbishop Soroka’s parents.

After the war many of these captives, especially religious people, ignored orders to return to Ukraine under communism and instead kept moving west and ultimately migrated to places like France, England, Australia, New Zealand the United States and Canada.

Archbishop Soroka’s parents, Ivan and Anna, opted for the latter and settled in Winnipeg, where he ultimately entered the priesthood and rose to auxiliary bishop before his appointment to Philadelphia as archbishop.

Uniformed men, believed to be Russian servicemen, walk in formation near a Ukrainian military base in Crimea March 7. (CNS photo/Vasily Fedosenko, Reuters)

In Ukraine, both the Catholic and Orthodox churches remained persecuted and underground virtually until the fall of communism in the Soviet Union in 1991 and subsequent Ukrainian independence. An exception was the small number of Orthodox clergy who cooperated with the Communist regime.

For most religious people the faith was preserved by “grandmothers teaching their grandchildren,” Archbishop Soroka said. “You had a huge population that had a Ukrainian spirit and a belief in God but lacking a catechism, a catechized population.”

Since the church emerged from underground there have been great strides, with churches, schools, convents and seminaries established especially through assistance from other countries including the United States of America.

“The seminaries are full; they may have a hundred seminarians where we have 10 here,” he said. “There is energy and enthusiasm and there is great hope for the future. You go into the cities and the churches are packed but there are not enough churches.”

Ukraine itself, which was dominated for centuries by other powers including czarist Russia and the Soviet Union, achieved full independence in 1991.

In the current crisis Russia has taken back Crimea and there is the possibility President Vladimir Putin will seek further territorial concessions, something that would be vigorously opposed by the Western Powers and both Catholic and Orthodox Ukrainians.

Archbishop Soroka concedes the Crimean annexation will probably stand, especially because the West is unlikely to go to war over it.

“I think the world is going to try to prevent it from going any further,” he said. “The world has a strong responsibility of condemnation about this; sanctions and so on.”

Russians themselves, he believes, “may get up and say, ‘that’s not who we are.’ My hope is they will come and question their leadership. There are a lot of people in Russia who are very oppressed. The West has got to stand up. If they show weakness and cowardice then he will have his way for a while, and that is not good.”

As of this time, there have been several incidents against Ukrainian Catholics in Crimea. (See a related story here.)

“A few of our priests were arrested and interrogated,” Archbishop Soroka said.

The absorption of Crimea will more directly affect the Ukrainian Greek Catholics than it will Latin Catholics because as Archbishop Soroka notes, Latin Catholics are recognized in the Russian Federation and can register their churches. But Russia does not recognize the Ukrainian Orthodox Church as a distinct entity separate from the Moscow branch and they may not be able to register their churches.

“But (the priests) escaped across the border into the mainland,” the archbishop said. “There is already a kind of harassment that has made Catholics feel unwelcome.”

This also holds for other denominations, he believes.

Although any persecution of Orthodox Christians in Crimea is very unlikely, further conflict between Russia and Ukraine could create problems within Russian Orthodoxy, Archbishop Soroka suggests.

Worshipers pray at a prayer service for peace in Ukraine March 16 at the Philadelphia’s Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception. (Courtesy of The Way/Ukrainian Archeparchy of Philadelphia)

The history of the Orthodox in Russia traces back to Ukraine itself, which was Christianized by missionaries from Constantinople in the 10th century and spread from there to Russia proper, which in time became the dominant center for Orthodoxy. Russia became known as a “third Rome,” after Rome and Constantinople.

At least in numbers of congregations, but not necessarily most adherents, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchy is technically under the jurisdiction of Patriarch Kirill of Moscow.

It has been suggested by Archbishop Soroka and others if relations between the Russian Federation and Ukraine worsen, the Ukrainian branch of the Orthodox Church of Moscow might declare independence and become an entity itself.

Because the Ukrainian branch makes up so large a part of the Moscow Patriarchate, the prestige of the Patriarchate would be greatly diminished.

Rather than see this happen, Archbishop Soroka and others speculate, Patriarch Kirill, who has a close relationship with Putin, may persuade him to take no further steps against Ukraine.

Whatever happens, it is all in God’s hands. “The power of prayer gives us hope,” Archbishop Soroka said.

***

Lou Baldwin is a freelance writer in Philadelphia.

PREVIOUS: Use social media and invite Pope Francis to Philadelphia

NEXT: Archbishop Chaput discusses HHS mandate, divorced Catholics

Share this story