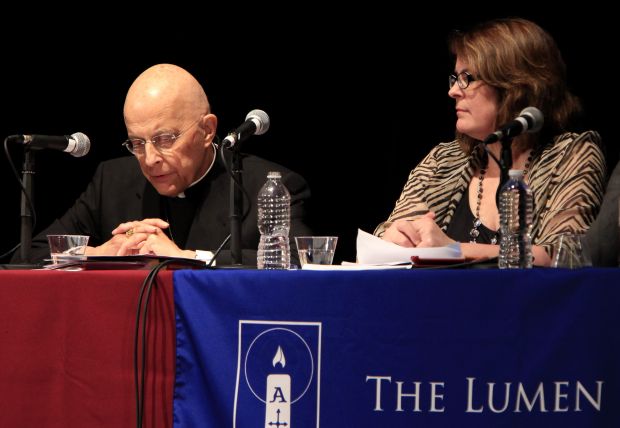

CHICAGO (CNS) — Chicago Cardinal Francis E. George opened the Lumen Christi Institute’s sixth annual conference on economics and Catholic social thought by acknowledging the difficulty of the endeavor: that while economists can sit in the same room, share a dais even, it’s unclear whether they are truly communicating.

For that reason, this year’s conference, “The Human Person, Economics and Catholic Social Thought,” was designed to go back to the basic idea of what a person is in each discipline, in hopes that they could better understand one another.

“This conference began with the idea that we were working at cross purposes,” Cardinal George said in welcoming the panel and audience to the discussion at the University of Chicago’s International House April 3.

In previous conferences, which contemplated the idea of a “moral economy,” he said, economists generally did not acknowledge the economic impact of gratuity and solidarity, both concepts discussed in Pope Benedict XVI’s encyclical “Caritas in Veritate” (“Charity in Truth”) while religious leaders responded with “truisms that may have sounded platitudinous.”

The Lumen Christi Institute tries to strengthen and nourish contemporary intellectual culture by deepening knowledge of the Catholic tradition, and to build up the Catholic presence in higher education by fostering the cultural formation of higher education.

Mary Hirschfeld, associate professor of economics and theology at Villanova University, offered the keynote talk, saying that she had to reconcile the language of the two disciplines after earning doctorates in both.

Economics and Catholic social thought do share common goals, she said.

“There is no one here who does not want to see low unemployment, high wages and an end to poverty,” she said.

But theologians often are put off by economists talking only about people acting in their own self-interest, she said. That doesn’t take into account that “self-interest” can apply to helping other people, if that’s what a person wants to do. “That means that people pursue the goods they value,” Hirschfeld said.

For example, Blessed Teresa of Kolkata would have used economic decision-making to figure how best to use her resources to help poor people, because that was what she was interested in doing.

What economists may not understand is that the ultimate human goal might not be simply having more goods — no matter how noble those “goods” may be — but in making their lives better reflect the ideal given by God.

“Human progress is not an advance in having, it’s an advance in being,” Hirschfeld said.

Respondents to Hirschfeld’s talk shared different ways economists and theologians could work together.

Jesus Fernandez-Villaverde, a professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania, said that “economics clarifies the requirements of natural law,” and that anyone trying to design a great — or even a workable — society must take into account basic economic principles, including the ideas that resources are limited, that incentives matter and that it’s impossible to know all the motivations and preferences on sides of a transaction.

Rachel Kranton, the James B. Duke professor of economics at Duke University, discussed the idea of how identity affects economic decisions. People define themselves as members of groups related to society in any number of ways, from gender to race to religion to work title to social class.

Those identities play into not only their preferences — the traditional way economists have looked at the choices people make — but also the norms and imperatives that they feel they must obey.

“Identities give motivations for people’s decisions,” she said.

Both identities and the norms associated with them can be changed, she said, and they can encourage both behavior that would be considered beneficial for the common good and behavior that is harmful.

“Human history is full of conflicts” based on group divisions, she said. “They can say, it’s OK to exploit some people, those who are not like us.”

F. Russell Hittinger, the William K. Warren professor of Catholic studies and research professor of Law at the University of Tulsa, Okla., offered the last response, saying there are many situations in which it would help church leaders to think like economists, if only to better understand the consequences of decisions they are making.

For example, Charlemagne’s decision to end the practice of executing pagans who refused to convert to Christianity might be the objectively moral decision, but it would have been helpful for him to know how that might affect emigration, marriage patterns and other conditions in his realm.

However, he said, it’s important for economists to also recognize “the limits of what it means to think like an economist.” Catholics, over the past 2,000 years, have come to understand the value of many disciplines; economists must figure out where thinking like an economist makes sense and where it does not.

The April 3 panel discussion was the first part of the conference, which was co-sponsored by the John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought, the International House Global Voices Program, the Seng Foundation Program for Market-Based Programs and Catholic Values, and the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts at the University of Notre Dame.

It continued April 4 with a panel discussion on “The Human Person: Fundamentals from Catholic Social Thought,” which included a talk from Bishop Marcelo Sanchez Sorondo, chancellor of the Pontifical Academies of Sciences and Pope Francis’ personal representative for the new anti-slavery Global Freedom Network.

***

Martin is a staff writer at the Catholic New World, newspaper of the Chicago Archdiocese.

PREVIOUS: Le Moyne’s new president is first laywoman to head Jesuit college

NEXT: New York Catholic all-girls high school founded by U.S. saint to close

Some thoughts on this topic. The notion of “insatiable wants” that I learned in First Year Economics may be erroneous for some people. The news story does begin to address that. Secondly regarding “limited resources” which years ago included land, labor, capital and entrepreneurship falls somewhat short by not acknowledging “creative intelligence” of people. Whether the endeavor is music or literature or scientific research or invention, human creativity (which some believe is a gift from God), has no discernible limits.

Also economics can be limited in addressing whether what is good economic theory and behavior, such as having marginal costs equal marginal revenues can be seen to be a “good” if practiced by a dealer of illegal drugs.

It what is illegal always unjust?