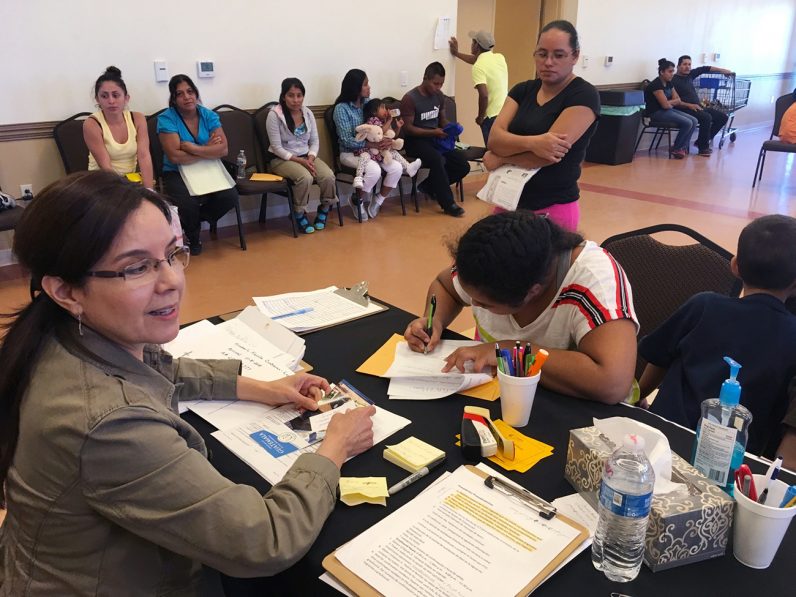

A volunteer from St. Anthony Parish in Upland, Calif., gathers information from asylum-seekers Nov. 9, 2018, to help them make travel arrangements. (CNS photo/courtesy Diocese of San Bernardino)

LOS ANGELES (CNS) — When the Trump administration started to systematically separate asylum-seeker families as part of a “zero tolerance” immigration policy at the border just more than a year ago, the objective was to deter people from continuing to seek protection in the U.S.

Carlos, 34, and his son Enrique, 13 (not their real names), had to flee Guatemala at the very same time that this policy was in full effect between May and June of 2018 — and they suffered the brunt of it.

[hotblock]

They were separated for more than two months and for most of that time, Carlos didn’t know where his son was.

“I had no intention of leaving my country, where I lived very well by planting and harvesting in season and then buying and selling in the market in Guatemala City,” explained Carlos, a slight man whose soft demeanor turns fierce when thinking about losing his son.

“To think that I left Guatemala because corrupt police threatened my life and my son’s, to come here and have officials take my son away, it’s unbelievable,” he told Angelus, the news outlet of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles.

“What’s the difference? They were doing the same thing here that they were threatening in my country,” Carlos added during a June interview in Southern California, where he awaits another court hearing on his asylum application while he and his son stay with a family friend from Guatemala.

In this past year, families like Carlos’ were helped by an army of activists and lawyers who stood up to fight the federal government’s policies, and by church volunteers offering legal and social assistance to thousands of others who have come since.

The need seems overwhelming.

In Los Angeles, 18 attorneys work in overdrive at Esperanza Immigrants’ Rights Project, a project of Catholic Charities, where they are still processing and awaiting court dates on the cases of 35 of the families separated last year at the height of the “zero-tolerance” policy.

[tower]

“The cases are ongoing, we filed asylum applications and are waiting for hearings; most of these cases take a long time,” said Patricia Ortiz, program director for Esperanza. “We have seen the importance of having attorneys, because some of these cases would never make it without one.”

For example, Esperanza’s attorneys took the case of an indigenous woman from Guatemala who had initially been denied her credible fear interview. She had been interviewed in her language, but she was too busy worrying about where her child was to understand the process and what was going on, said Ortiz.

Last year, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and Guadalupe Radio helped raise enough money to fund the work of one attorney and a little bit extra for gift cards for the families, said Ortiz. However, money remains tight.

“We not only have the family separation cases, we have hundreds of other families seeking asylum that we are representing,” said Ortiz. “This crisis hasn’t stopped, and any new rules aren’t going to fix the bigger issue that causes these migrants to leave their country.”

Carlos and his son Enrique illustrate one of the typical reasons people leave their country — fleeing for their lives: They get targeted by gangs or, in his case, corrupt police.

Carlos had been kidnapped for ransom by members of the Guatemalan National Police that turned up in his small town one evening in May of last year. For two days they beat him up, until he gave up his brother’s phone number so they could call and request money in exchange for his life.

The money, worth a year’s earnings for Carlos, was found among the most affluent wholesalers at the market and taken as a loan by his brother. He was let go, but a couple of weeks later, another request came, this time for more money.

“They said that they would go after my son, who was then 12,” Carlos recalled. “So I told him we were going on an adventure, gathered a little money and left. My wife and my two small daughters stayed behind. That’s why I can’t publicize my name or my face.”

The trip took a month and at least 12 risky jumps between trains in Mexico. At the border in McAllen, Texas, he stepped over the line a few times until he saw Border Patrol agents coming at him. “I wanted to do things legally, and go to them with an asylum request,” he said.

[hotblock2]

Four hours later, an agent took his son away. Nobody told him where he was going or why. They took Carlos to court in Texas, where he was quickly convicted of illegal border crossing and sentenced to three days in jail. Then he was transferred to Port Isabel Detention Center, where he continuously made requests for information about his son.

“They kept telling me they didn’t know. I would answer: ‘How come you didn’t know? You took him,’ ” he remembered. “One time an ICE agent told me that it was my fault for doing this and that he was going to be adopted.”

One night at the detention center, Carlos was watching Telemundo when he heard that federal Judge Dana Sabraw had issued an injunction ordering families to be reunited. He figured that his son had to be in one of the children’s shelters, and told a social worker that if his son was not given back to him, he would call the TV station.

“Two days later, they released him to me,” he recalled. “I thought I was never going to see him again, that I had come to this country to give my son away.”

They both now live in Riverside, California, in the home of a family friend from Guatemala, while waiting for their court date.

***

Marrero writes for Angelus, the news outlet of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles.

PREVIOUS: Chicago Public Schools urged to take lesson from Catholic action on abuse

NEXT: Washington state bishops call for ‘comprehensive immigration reform’

Share this story