WASHINGTON (CNS) — The dates may not be printed on many people’s wall calendars, but they mark a certain passage of time nonetheless: the “October surprise” every four years before a presidential election, “Black Friday” the day after Thanksgiving in November to mark the start of the holiday shopping season, and the “December dilemma,” in which families figure out how much they can afford to give to charities to qualify for best possible tax deductions or tax credits.

This December, the dilemma takes on an added dimension. As Congress and the White House scramble to find new sources of revenue to go with budget cuts to achieve deficit reductions and avert a so-called “fiscal cliff,” one tempting source for creating revenue is a ceiling on tax deductions.

Father Larry Snyder, president of Catholic Charities USA, predicted that if tax deductions are capped, “there will be a definite decrease in the philanthropy that charities will see.”

[hotblock]

Leaders of charitable organizations flew en masse to Washington Dec. 4-5 to lobby members of Congress and White House staffers to leave charitable contributions alone.

“First of all, it’s not just a tax incentive for millionaires,” Father Snyder said. “The majority of the gifts that come to Catholic Charities organizations — and I think last year we had almost $900 million in charitable giving — they are $1,000, $2,000, $5,000 gifts.

“But those people do itemize,” he added. “It’s 30 percent of the public, but the number of millionaires is far less than that. It really is folks wanting to support the work of the nonprofit sector.”

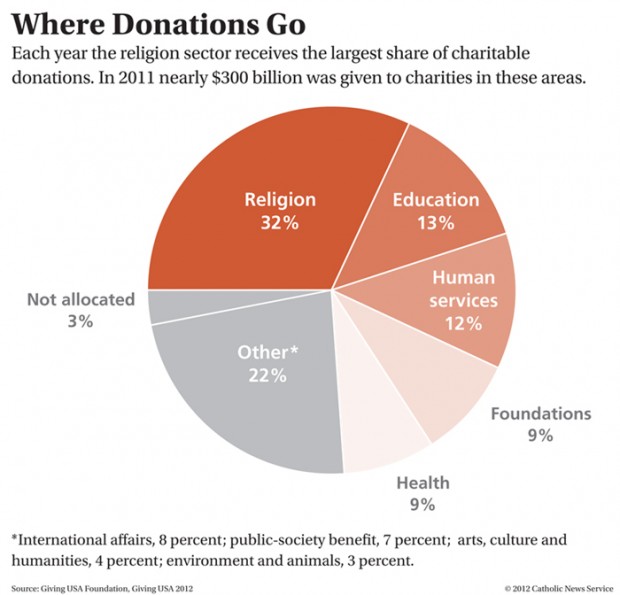

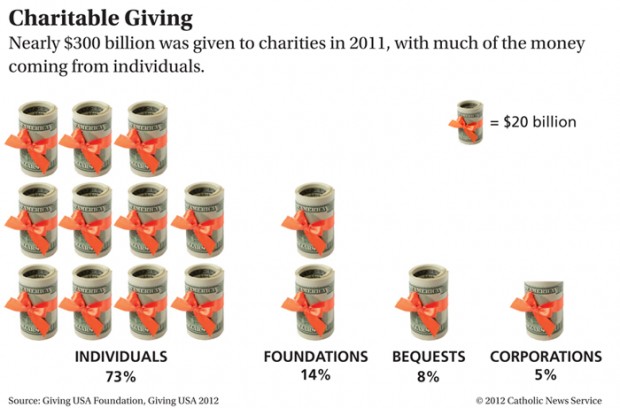

Released this June, a report on giving in 2011 from the Giving USA Foundation and the Center on Philanthropy, its research partner, showed that close to $300 billion was given to charities. Individuals accounted for the “vast majority” of the charitable gifts, which has been the case, the foundation said, since it first began examining charitable donations in 1955.

Religious organizations received $95.88 billion in 2011 and they remain the largest type of recipient, the report said.

Frank Wright, chairman of the National Religious Broadcasters, a largely Protestant organization, called charitable deductions “a public policy that has proven its worth for nearly a century.” He added, “Rather than capping or otherwise constraining this long-standing deduction, the federal government ought to expand opportunities for the charitable impulse of Americans to thrive.”

It remains to be seen whether budget negotiators will heed the call, as House Republican leaders Dec. 4 expressed a willingness to raise $800 billion in revenues without raising tax rates.

President Barack Obama, in a Dec. 4 interview with Bloomberg TV, dismissed the concept of a deduction cap.

“If you eliminated charitable deductions, that means every hospital and university and not-for-profit agency across the country would suddenly find themselves on the verge of collapse. So that’s not a realistic option,” Obama said.

A cap would be “a blow, as many have commented, to already-hard-hit charities that are just starting to get over the recession,” said Elizabeth Boris, director of the Urban Institute’s Center on Nonprofits and Philanthropy, at a Dec. 4 institute-sponsored panel discussion.

“Philanthropy does things that government doesn’t do well” or “doesn’t do at all,” said panelist Robert Grimm, director of the Center for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Leadership at the University of Maryland School of Public Policy.

Grimm pointed to his own experience growing up in a rural Iowa town of only 300 that was home to the state’s only professional theater company, thanks to philanthropy. He also pointed to the example of Benjamin Franklin, who created Philadelphia Hospital once he convinced the Pennsylvania state government to pay half the cost if he could raise the rest.

“Philanthropy allows each person to define their version of the social good,” with the money they contribute becoming “their risk capital,” Grimm said, adding that if given a proposition that’s “high-risk, high-reward, and is going to fail eight times out of 10, do you think you’re going to get the federal government to do that?”

Dan McCabe, CEO of Causetown, which links projects and donors, said studies show those who give money to a project are more likely to volunteer their time with that project — and those who volunteer are also more likely to give.

“Giving is sort of the gateway drug to that engagement,” added Mari Kuraishi, co-founder and president of the GlobalGiving Foundation.

“The notion that foundations are the sole contributors to the public good is just not true. Online is a tremendous enabler of that fact,” Kuraishi said, pointing to Kickstarter and similar endeavors that look for investors for thousands of projects from making wool caps known as “surf beanies” to CD recordings.

Grimm suggested altering tax deductions isn’t the only threat to charitable giving. “Reducing personal consumption is going to reduce giving. More than capping (deductions on) giving, raising taxes will also reduce giving,” he said. Government cuts will also play into the equation: “Government is the biggest funder of nonprofits,” Grimm noted, and “the weak economy” has been at work in giving, since “nonprofits are very reliant on earned revenue.”

Urban Institute senior fellow Eugene Steurle said current tax policy already has an impact on giving, as many donors say they “give to the max,” meaning they give only so much to qualify for the largest possible deduction, but no more than that.

“We’re seeing fewer philanthropists but more givers,” McCabe said. The trick is to get more people engaged, he added, noting that people who spend “hundreds of hours in front of the TV” aren’t likely to be engaged or put themselves in a position to be approached.

McCabe said eight of 10 schools do outside fundraising, hawking items like gift wrap and chocolate bars, with school fundraising itself having become a $4 billion industry. But by the same token, Americans spend $4 trillion on dining and shopping, and local businesses would love the increased patronage in exchange for a percentage of the receipts donated to the school or cause. “Even if I move the needle a sliver, I can access new funds,” McCabe said.

“From the reports that we have back there is universal support for the charitable sector,” said Diana Aviv, president and CEO of Independent Sector, an umbrella group for nonprofits after meetings in congressional offices. “They want to support us. There is also support for the charitable tax deduction,” she added.

“But here’s the rub. We hear from a lot of staff,” not the representatives and senators themselves, Aviv said. With deficit negotiations lagging, she said she feared “the tax deduction might get caught up in a lot of bigger issues” if and when the talks heat up.

PREVIOUS: Supreme Court to hear cases on same-sex marriage

NEXT: Federal judge calls pro-life license plate ‘viewpoint discrimination’

As one of probably millions of Americans who gives money without taking any deductions because I earn too little to be able to itemize, I don’t see why people would stop giving money away if they believe in the cause they are supporting. Are the poor the only ones who believe that it’s okay if the right hand (the govt) doesn’t know what the left hand (the donor) is doing?

In my view, the charities sector of the US economy has gotten way out of wack in that the Executives of many of these charities make far too much money. For example, the Executive Director of the American Red Cross makes around a half million dollars. Similarly, the Head of the Knights of Columbus also makes around a half million dollars. The GOP plan to eliminate charitable deductions may help to reduce the salaries of these Executives which would be good for everyone (except the Executives).