St. Charles Borromeo Seminary, Wynnewood, announced on March 21 it has placed five portraits painted by Thomas Eakins on consignment for sale through Christie’s Private Sales in New York. Other pieces of art have also been placed for sale with other auction firms.

Funds from sale of the paintings, which was first discussed last October, will be applied toward renovations over the next three to five years necessary for the consolidation of the College Division on the lower side of the campus into vacant space in buildings on the older Upper Side, which since 1928 has only housed the Theology Division.

Additional funding for the consolidation is expected to come through the Heritage of Faith-Vision of Hope capital campaign and the sale of approximately 40 acres of the 75-acre campus.

(See a photo gallery of some the paintings here.)

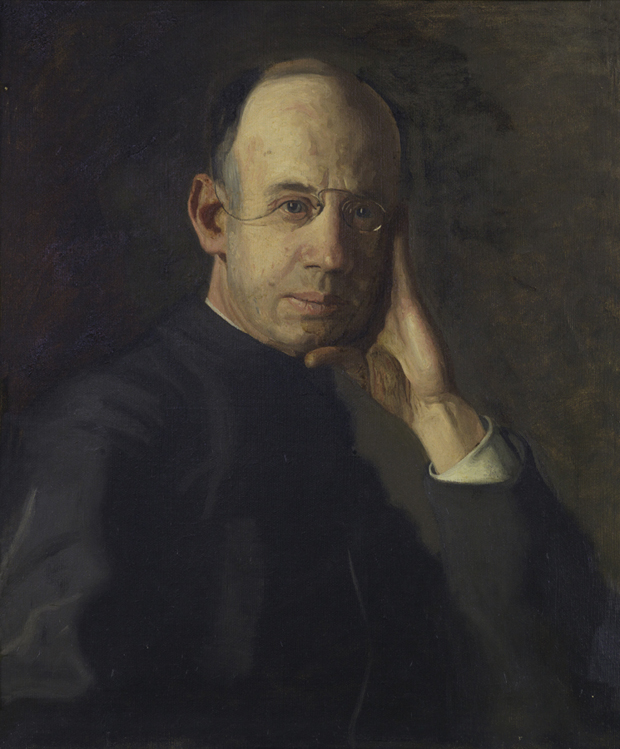

The Eakins paintings that the seminary plans to sell include “The Right Reverend James F. Loughlin” (1902), “Reverend James P. Turner” (1900), “James A. Flaherty” (1903), “Dr. Patrick Garvey” (1902) and “Archbishop James Frederick Wood” (1877).

“The seminary has long been a steward of these works, but it is the right time to seize an opportunity to do what is best for the artwork and for the seminary itself,” said Bishop Timothy C. Senior, rector of St. Charles Borromeo Seminary. “We will keep many of the paintings in our collection but the core mission of the seminary is to form men for service in the priesthood. We are not a museum.

“Our hope is that as a result of this decision the Eakins paintings can find a home where they can be well cared for and viewed widely by people from across the country. What we are doing is consistent with our overall efforts to reenergize the seminary and focus on its mission while building for the future.”

Other than the Archbishop Wood and James Flaherty portraits, the Eakins subjects were faculty members of St. Charles Seminary. Although Eakins was not a Catholic himself, during the first decade of the 20th century he and a friend, the Catholic Samuel Murray, would bicycle on Sundays out to the seminary where they would attend vespers and enjoy conversation with the priest-professors.

This was shortly after the death of Thomas Eakins’ father, Benjamin Eakins, and it is believed he obtained solace through these visits.

[hotblock]

The pleasant afternoons are memorialized in a way by a large mosaic in the rear of the Cathedral Basilica of SS. Peter and Paul in Philadelphia that depicts major ecclesiastical buildings in the archdiocese. As part of the image of St. Charles Seminary there is a tiny figure of a man on a bicycle, which represents Thomas Eakins.

The paintings were done free of charge by Eakins to the priests, most of whom left them to the seminary.

An exception is a portrait also included in the sale that is not the property of the seminary, but of the American Catholic Historical Society. It is called “The Translator” and it depicts Father Hugh T. Henry. He was a member of the seminary faculty as well as rector of Roman Catholic High School until he was appointed to the faculty of the Catholic University of America in Washington.

“The American Catholic Historical Society has been working in partnership with the seminary to include our painting, ‘The Translator,’ in the auction of other Eakins’ works that are owned by the seminary,” said Michael H. Finnegan, president of the ACHS. “Father Henry served as our society’s fourth president from 1897 to 1898. He convinced Eakins to present his portrait to our society, and our society in turn loaned it to the seminary, where it could be displayed in a proper setting along with the other prominent Catholics’ portraits.

“Our society house was not then, and is not now, a proper place to maintain and display such a fine piece of art,” Finnegan said. “It is our hope that all of the paintings will find a home where they can be preserved properly and available for public viewing. Our proceeds from any sale will allow us to establish an endowment to restore some of our other art, and continue our mission of collecting materials related to American Catholic history.”

James Flaherty, the only layman depicted in the portraits, was a Philadelphia lawyer and founder of the Knights of Columbus in Philadelphia and Pennsylvania. He went on to become Supreme Knight of the entire organization and filled that post during perhaps its most dynamic period.

Under his watch in World War I, because of a shortage of Catholic chaplains, the Knights recruited and paid priests to serve as chaplains. After the war the Knights organized training programs for returning soldiers, which became the model for the federal G.I. Bill after World War II.

The portrait itself was commissioned by the Philadelphia Knights and displayed in their headquarters until it was ultimately donated by them to the seminary.

In addition to the Eakins portraits, an undated painting by Colin Campbell Cooper, “St. Peter’s Cathedral” (St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome), has been placed for sale with Bonham’s in New York and a 1976 painting “Archbishop Jadot” (Archbishop Jean Jadot, apostolic delegate to the United States from 1973 to 1980) by Alice Neel has been placed with Sotheby’s in New York.

How much the paintings will bring, only time will tell. They are considered lesser works of Eakins, and were mostly painted as gifts to friends. The Msgr. Loughlin portrait, which is full-length, is probably the most valuable, according to Cate Kokolis, vice president of services and assessment at St. Charles who is most knowledgeable about the collection.

The Archbishop Wood portrait might have been the most valuable were it not for an ill-conceived attempt at restoration in 1930 that greatly diminished its value. This plays into Bishop Senior’s point — the paintings will be better preserved for future enjoyment if they are placed in an institution where they can receive the expert attention they deserve.

An older St. Charles Seminary history mentions at least 150 paintings displayed at the seminary, mostly religious art, but none are deemed as commercially valuable as those that are now being marketed, although some others may be sold at a future date.

One interesting painting that remains is the “Crucifixion” painted by Francis Martin Drexel, displayed in the Eakins Room. He was the father of Anthony Drexel, founder of Drexel University and grandfather of St. Katharine Drexel. He switched from art to investment banking which was much more lucrative.

But maybe not, considering that Eakins’ most famous work, “The Gross Clinic” (1875), was originally sold to Jefferson Medical College for $200 and resold by the now-university in 2006 for $68 million.

Eakins’ only religious work, a “Crucifixion” painted in 1880, could not attract a buyer because it was deemed “too graphic.” It was donated to the Philadelphia Museum of Art by the Eakins family in 1929.

Because of the art sale and the other planned fundraising methods the seminary is poised for future growth to 200 seminarians in residence, as well as hundreds of non-residential candidates for the permanent diaconate and full- and part-time students enrolled in the Graduate School of Theology.

The seminary will continue to make public announcements as it reaches milestones for future viability and sustainability. As it proceeds with these plans it will have ongoing dialogue with the archdiocese, Lower Merion Township where it is located and the community at large.

There is something sad about these paintings leaving the halls where they were placed after so many years, probably headed for the sterile galleries of far away museums. Yet somehow one guesses these long-dead professors would be happy, knowing that the sale of their portraits will help continue their life’s work — the formation of young men for the holy priesthood.

***

Lou Baldwin is a freelance writer in Philadelphia.

PREVIOUS: Largest crowd to date ‘mans up’ for Catholic gathering

NEXT: Cathedral Mass offers prayers, lifts ‘a dark veil’ on clergy sexual abuse

Share this story