WASHINGTON (CNS) — Healing and reconciliation continue 20 years after Rwanda’s 100 days of genocide, making the central African nation a strong example for troubled states to emulate, international observers said.

Hutus and Tutsis, the country’s primary social groups, now work alongside each other to rebuild a country that was often afflicted with political and social violence that ultimately led to genocide during its first three decades as an independent nation.

Still, the world continues to struggle to develop ways to prevent atrocities in the first place, leaving questions about how much leaders have learned from the most horrific period in Rwanda’s history.

(See related video)

Almost daily, reports from Congo, Central African Republic, the Darfur region of Sudan, Cambodia, Syria and elsewhere shock the senses. Killings are used as a tool to terrorize and intimidate. Violence can also take the form of rape or torture. Often the level of response to any given situation depends on the geopolitical forces at play in a world no longer solely dominated by two superpowers.

Observers told Catholic News Service that while reports of mass atrocities have declined in the 21st century, the likelihood of smaller-scale incidents remains. They said countries would do well to bolster diplomatic initiatives and support local peacebuilding programs in an effort to head off mass atrocities.

“I think you need to get way ahead of genocide long before it occurs. If you have to use force to stop it, it’s almost too late,” said John Shattuck, president of Central European University in Budapest, Hungary, who served as assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights and labor under U.S. President Bill Clinton.

[hotblock]

Shattuck explained that genocide in Rwanda and almost simultaneously in Bosnia-Herzegovina, where the Serbian army indiscriminately killed Muslims, occurred as the world realigned after the collapse of the Soviet Union. He said the United States was “caught quite flat-footed” when the Rwandan violence broke out April 7, 1994.

Today, Shattuck, who helped negotiate the Dayton peace accord that ended the Bosnian war, believes the U.S. and the rest of the world are “becoming more knowledgeable about how to predict and head these terrible things off.”

“There are tools that have been developed to be able to intervene early without military intervention,” he said.

“Whenever possible, international organizations need to be at the center of these efforts to head off mass atrocities and genocide,” Shattuck told CNS. “But leadership roles have to be played by the U.S. and other world powers.”

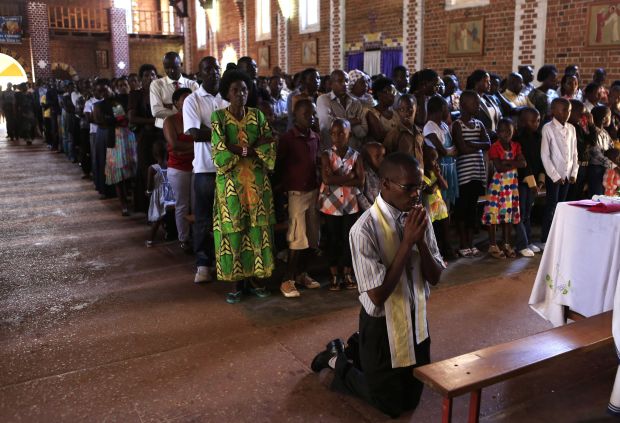

A woman holds a child during Mass at St. Famille Church in Kigali April 6. (CNS photo/Noor Khamis, Reuters)

Partly in response to events in Rwanda and elsewhere, the U.N.’s 2005 World Summit adopted a statement calling for nations to have a “responsibility to protect” populations from genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing. Under the principle of “responsibility to protect,” if an individual state cannot respond adequately, other nations can take collective action as established by the U.N. Charter.

Marie Dennis, co-president of Pax Christi International, cited the principle in suggesting that nations refrain from automatically responding militarily to threats of mass violence when such long-standing practices as diplomacy and economic sanctions are exhausted.

“The responsibility to protect or to prevent genocide should not become tangled in the tension between pacifism and the use of military force,” Dennis explained. “Unarmed peacekeepers can be effective if well-trained, equipped and deployed in sufficient numbers. Accompaniment, international exposure or shaming, the withholding of media attention, providing physical protection and other strategies should be developed and tested for us on a scale sufficiently large to make a difference.”

Many developing countries as well as those recovering from mass violence have seen the rise of peacebuilding initiatives by nongovernmental organizations working in local communities.

Rwanda’s efforts at peace and reconciliation began almost immediately after the genocide, in which as many as 1 million people died. The Catholic Church has been among the institutions undertaking wide-ranging reconciliation efforts.

The Episcopal Justice and Peace Commission of Rwanda, established by the country’s Catholic bishops, has turned to base communities to build understanding and peace. Catholic Relief Services worked with the bishops in establishing its own peacebuilding program that continued for about 15 years.

Marie-Noelle Senyana-Mottier, the agency’s acting country representative in Rwanda, told CNS that hundreds of volunteers continue to convene peacebuilding groups in parishes, schools and communities across Rwanda, even though CRS ended its involvement in the effort in 2012.

Under the program, CRS trained 40,000 facilitators to help with reconciliation and build understanding among the Tutsis and Hutus.

The skulls and bones of Rwandan victims rest on shelves at a genocide memorial inside a church at Ntarama, just outside the capital Kigali, in this 2010 file photo. (CNS photo/Finbarr O’Reilly, Reuters)

“I think the main task is for people who live in the same country to have the same vision, to be self-reliant,” Senyana-Mottier said of the peacebuilding initiative. “That’s what CRS, together with its church partners and other partners, are really trying to do.”

Senyana-Mottier arrived in Rwanda exactly one year after hostilities broke out. She said she was impressed by how people were cooperating to rebuild the water, electrical and telephone systems, even while sharing their grief.

But still, Senyana-Mottier said, two decades is not a lot of time to heal.

“It’s very early, 20 years is a very short period of time after what’s happened in Rwanda. People start to remember what happened,” she told CNS.

Much of the hard work on peacebuilding in Rwanda revolves around conflict resolution. Andrea Bartoli, dean of the School of Diplomacy and International Relations at Seton Hall University, South Orange, N.J., said he believes the effort can be a lesson for other countries experiencing conflicts arising from tribal, ethnic and religious differences.

Bartoli cited efforts in the Central African Republic by Archbishop Dieudonne Nzapalainga of Bangui and Imam Omar Kobine Layama to prevent hostilities among militias from escalating into mass killing.

The bishop’s role is particularly important when placed in the context that Rwanda, Africa’s most Catholic country, experienced genocide of horrific proportions, he said, noting that some of the killing occurred in churches.

“At the moment of the genocide, religion became either irrelevant or was manipulated and misused by people,” he said.

Ernesto Verdeja, assistant professor of political science and peace studies at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, credits nongovernmental development programs, many established by some of the hundreds of thousands of women whose husbands were killed, as key to minimizing mass violence.

“Women tend to be marginalized, but also the most active peacemakers,” he said.

He pointed to Rwandan women who have started business cooperatives, led educational programs and coordinated support groups for grieving widows. Nearly two-thirds of the seats in the Rwandan parliament are held by women.

“Such programs need support,” he said. “The trick is how to do this in a way that reinforces the autonomy and power of local groups.”

PREVIOUS: Court declines cases eyed over same-sex marriage, campaigns, executions

NEXT: Diocesan tech staffs have concerns about end of Windows XP support

Share this story