VATICAN CITY (CNS) — Hidden beneath Albania’s long legacy of interreligious harmony and peace lie the turmoil and bloodshed of an ancient vigilante code that affects thousands of families, many of them Catholic.

Called “blood feuds,” they stem from a traditional Albanian code or “kanun” that sanctions murder to restore a family’s honor after a member experiences an affront, injustice or killing.

The feud can start with a quarrel or offense, which then triggers the murder of any male member, even teenagers, in the perpetrator’s family.

[hotblock]

When Pope Francis visits Tirana Sept. 21, he is expected to highlight the nation’s Muslim-Christian cooperation as a successful model for the rest of the world. But one expert anticipates the pope will also chastise the Balkan nation for its lingering social strife, political corruption and barbaric honor code of revenge.

“We’re really good when it comes to collaboration and coexistence among religions, but we’re not that great from the social-issues point of view,” said Luigj Mila, secretary-general of the Albanian bishops’ peace and justice commission.

This established right to spill blood in return for bloodshed has meant the practice has cycled and spanned over generations.

At least 7,000 people have been killed in the past 20 years alone and some 1,500 families have members living as virtual prisoners in their house since the code considers the home sacred ground, exempt from an avenger’s intrusion.

But even voluntary confinement wreaks havoc as the person is unable to work or go to school and the whole family can suffer from fear, trauma and depression.

An extensive set of rules, the “kanun” is thought to date back to prehistoric times and was codified in the 15th century to offer law, order and a system of justice. Its practice was squelched during the oppressive Stalinist regime from 1944 to the 1990s, but gained a resurgence with the nation’s newfound freedoms.

The blood feud practice had been isolated in the mountainous northern region, but has slowly trickled down to nearby cities as villagers flocked to urban areas for better opportunities or to flee vengeance back home, Mila said.

An estimated 70 percent of the murders involve Catholics.

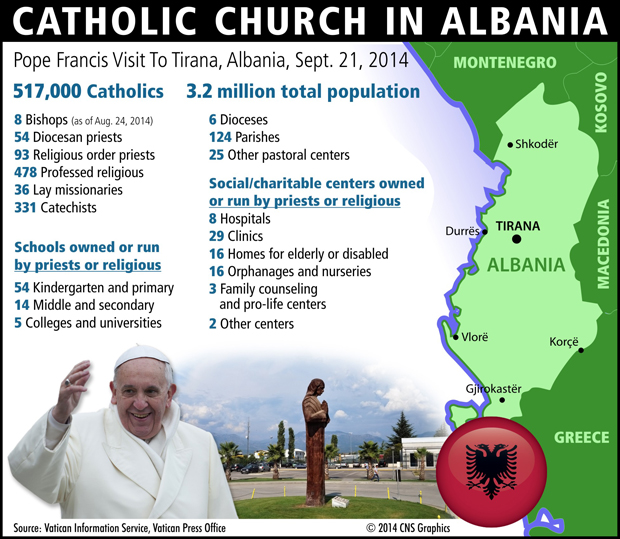

Mila said that’s because Catholics make up the majority in the mountains, where they fled during the Ottoman incursions beginning in the 14th century. It’s estimated that among Albania’s 3 million inhabitants, Catholics make up 16 percent of the total population, Muslims about 65 percent and Orthodox 20 percent.

The killings have been “a scourge” and “very painful” for the Catholic Church, Mila said, as incidents of Catholics killing Catholics call into question the sincerity and truth behind the Christian message of love and peace.

“It doesn’t work in the church’s favor,” he said.

Priests and religious, especially Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries, he said, spent years “walking into the mountains trying to reconcile the feuding families.”

The task was made even harder because “the justice system in Albania doesn’t work very well,” he said, so the traditional code of honor and retaliation was often seen as the only viable law of the land.

With Mila’s help, the three Albanian bishops in the North decided to take the situation into their own hands.

Led by Archbishop Angelo Massafra of Shkoder-Pult, the bishops published a decree in September 2012 declaring that any Catholic who does not obey God’s commandment of “Do not kill,” faced automatic excommunication.

Such a drastic measure was necessary, the bishops’ letter said, because church teachings have been ignored.

“Now it is time to apply the penalties that the holy church and the (canon law) foresees in such cases,” that is, the most severe of church sanctions.

Mila, a lawyer, said the impact was immediate.

As soon as an honor killing took place, the bishop publicly declared the penalty of excommunication on the murderer, sending shockwaves throughout the country.

“It had an effect because, even if the person isn’t very religious, they fear divine condemnation. The psychological-spiritual pressure is very strong” and people abhor the thought of being “cursed” or excluded, Mila said.

The bishops’ stance also had an impact on the Albanian government, which, Mila said, then decided to “take control.”

Authorities finally accepted that there was a problem and acknowledged its seriousness, something they had never been done before, he said.

“I’m sure it has served the good because it also gives people the possibility of repenting, of turning back and become part of the family” of the Catholic Church again, he said.

In the run-up to the pope’s visit, Mila said the bishops have called on all feuding families to reconcile.

“And I know the pope will ask people to forgive each other and stop this vendetta,” he said.

PREVIOUS: Seven decades later, remembering monks massacred by Nazis

NEXT: Pope: Christians’ only bragging rights are being a sinner, being saved

Share this story