Less than a decade ago, refugees from war-torn Lebanon were fleeing to stability in neighboring Syria. Today the hosts are becoming the guests as the flow of refugees has gone into reverse.

Less than a decade ago, refugees from war-torn Lebanon were fleeing to stability in neighboring Syria. Today the hosts are becoming the guests as the flow of refugees has gone into reverse.

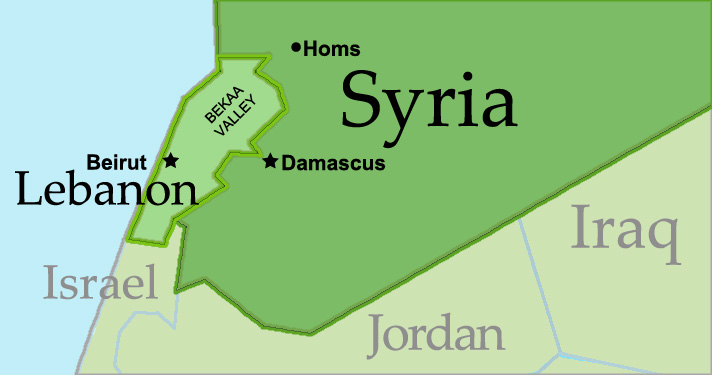

The vice of Syria’s civil war and the encroachment of Islamic State fighters has forced Syrian civilians out of the country and into Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey.

Soha Menassa of Catholic Relief Services has seen first-hand the suffering of Syrians, especially children, from her station in Beirut for the past three years, and how Catholic agencies in Lebanon are relieving some of the massive human needs.

[hotblock]

She spoke to about a dozen people March 3 in the CRS Rice Bowl Lenten Series at the Archdiocesan Pastoral Center in center city Philadelphia.

Lebanon’s population of 4.5 million currently is hosting 1.5 million refugees from Syria, or one out of every three people is a refugee.

By comparison, imagine the United States feeding, housing and educating 105 million additional people who fled their home with little more than the clothes on their back.

The difference is, “Lebanon is already suffering an economic crisis,” Menassa said, noting that even in 2006 Lebanese were still moving into Syria to escape violence in their country.

(Watch a video on the situation in Lebanon by Catholic Relief Services, below.)

She is aware that in addition to the 2.5 million refugees spread across her country, Jordan and Turkey, another 7 million are internally displaced in Syria, “going from town to town” seeking safety from the fighting.

While they don’t have to fear bullets and bombs in Lebanon, the refugees recently endured the harsh winter that lashed that part of the Middle East with heavy rain, wind and some of the coldest temperatures there in memory.

The result is living conditions that would strain the heartiest souls. “They are living in mud, with no running water,” Menassa said. “They have to buy it to drink and wash, then dry the wet things in the sun,” she said, a task made harder by the cold.

The efforts of CRS and the Catholic agency Caritas Lebanon, along with a project of the Good Shepherd Sisters, concentrates on meeting acute needs in the Bekaa Valley in the mountainous northeast of the country.

CRS helped obtain some shelter for the refugees, though it is tight for them. Two hundred families of about nine people each, on average, are occupying 100 tents.

Because of the heavy snow firewood is not available, but the tents connect to electricity for small heaters and lights. They are especially valuable outside the tents to keep wolves at bay, Menassa said.

Beyond providing food and basic needs, the tents do offer a safe space for children who nonetheless report they are lonely because many are not enrolled in schools. Lebanon has opened its public schools to refugees, even though its social institutions are buckling under the strain of providing for so many newcomers.

Nevertheless, many children work to earn money for their family in the absence of their father. Most refugees are women and children under 11, according to United Nations data.

[hotblock2]

Two Good Shepherd Sisters working with some staff and many women refugee volunteers are using a community center primarily for children’s needs. Since 2011 what had been an after-school program now runs in two shifts day and night, and the school is full, with room for no more kids.

That’s no wonder, because they’re serving many of the 600,000 refugee children in Lebanon, according to Menassa.

“The school provides one hot meal a day, and they can dance, be kids, and laugh,” she said.

But the war from which they fled is never far behind. During the day the children show sad faces and draw pictures of guns and destruction; at night they wake with nightmares. According to Menassa, 45 percent of the children experience post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD) and 60 percent depression.

“It’s pretty alarming” to witness, Menassa said, but in response the sisters have begun a psychological support ministry to introduce therapeutic play, “and someone to listen to them,” she said. They love puppets, she added, which “help them express themselves. They can communicate with the puppet or use it as a mask to communicate with other people.”

While challenges exist such as a shortfall of food, new border restrictions and some incidents of harassment, the Syrians are generally grateful to their Lebanese hosts, Menassa said. That is because the refugees view themselves as the proud, middle-class people they were in Syria, and they want to go back home there when they can.

“We have hope they can rebuild Syria,” Menassa said.

In the meantime life, as it is in Bekaa, goes on. “Babies are still being born,” she said. And the Muslim refugees are getting a glimpse of Christianity that they never knew before.

They saw the word “Catholic” in the CRS signs “and they thought ‘Catholic’ meant assistance,” Menassa said. As they are finding out, providing that assistance “is what it means to be Catholic and Christian,” she said.

One attendee at her talk last week was Father Vincent Farhat, a Maronite Catholic priest and administrator of St. Maron Parish in South Philadelphia. The Maronite rite of the church has its ancient roots in Lebanon.

He said his congregation has aided people in the Middle East for at least the past 50 years and continues to “do everything we can through organizations to help.” He has noticed that in Lebanon, “Christians take in Muslims and Muslims take in Christians.”

“With your prayers and assistance,” he told the talk’s guests, “we will be able to make a difference.”

***

The next speakers in the CRS Rice Bowl Lenten Series, held from noon to 1 p.m. at the Archdiocesan Pastoral Center, are Denis Okema, a Ugandan who escaped captivity in the Lord’s Resistance Army to become a peacebuilder in Africa, on March 18; and Sister Kim Kessler, C.S.R., who will speak about her work with hungry people in this local area at the Drueding Center’s Green Light Food Pantry in Philadelphia, on March 25.

PREVIOUS: Vatican watcher sees ‘something extraordinary going on’ with Pope Francis

NEXT: Parish offers warm welcome to 8 special men

Share this story