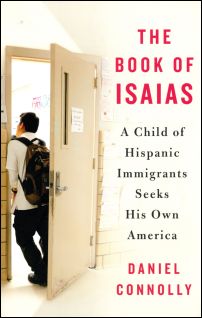

WASHINGTON (CNS) — Nobody’s story is cut and dried, as longtime immigration reporter Daniel Connolly learned when doing reporting for his book, “The Book of Isaias.”

WASHINGTON (CNS) — Nobody’s story is cut and dried, as longtime immigration reporter Daniel Connolly learned when doing reporting for his book, “The Book of Isaias.”

Connolly tracked the Mexican-born teenager throughout his senior year of high school in Memphis, Tennessee, and followed up at critical junctures in his life afterward.

Isaias’ story has its share of contradictions. While born in Mexico, he migrated with his family to the United States without documents. The family settled in Memphis, not the first city one thinks of as an immigrant hotspot.

Although Isaias identifies as atheist, Connolly noted that he read a Bible regularly to see what teachings matched his emerging philosophy. And, for a brief time, Isaias attended an evangelical Christian college in Memphis.

Then there’s also the homesickness Isaias’ parents felt for their native Mexico, but they had to wrestle with what to do about Isaias’ little brother, who was born in the United States and is a U.S. citizen, since the likelihood of the parents’ ability to return north would be quite low.

[hotblock2]

“When I met him, I was struck by a number of things,” said Connolly, a Catholic. “He was just hands-down really, really bright. The other thing about him: He was expressing these big doubts about college and the value of college. He seemed extremely bright, but negative on the value of future study. He talked about cleaning houses.

“What I was really trying to write about in the book was human potential,” Connolly added, “the big question about what’s going to happen to him and how he’s going to use that. It was a compelling sort of framework for this larger thing about the millions and millions of children of immigrants in our society.”

Returning from his yearlong leave of absence at the Memphis Commercial Appeal daily newspaper, Connolly wrote a series on Isaias’ life in December 2013, several months after he’d graduated from high school. “The most tangible result was that people who read it came forward and gave him money, basically. There were a lot of adults in the community, or several at least, who reached out to him and tried to help him out.”

Because Tennessee state law forbids immigrants in the U.S. without documents from enrolling at public universities, one path was blocked. Isaias also had his own ambivalence about attending college.

“The way his story turned out was not the way that I anticipated it,” Connolly said. “It turned out to be something way more complicated.”

[hotblock2]

The book, though, is more about Isaias and his situation. “One of the things I try to do in this book is to explain how we got to where we are as a country in terms of immigration as a country,” Connolly said. “Basically, businesses and the federal government made decisions that allowed millions of immigrants to live here illegally, but for all practical purposes tolerated. The practical effect is that they live in this country with limited rights.

“For example, as a U.S. citizen, I can use my U.S. passport to fly to Mexico City and back,” he said. “But if you’re a Mexican citizen living here illegally, you can live or work pretty much freely, but you can’t travel back and forth. More or less openly, but with limited rights. That is a problematic situation for them.”

Connolly said he got his first awareness about immigrants during his college years.

“I was coming back to visit my family in Memphis. It was around this time there was a large influx of Mexican immigrants into our neighborhood in Memphis. Many of them were Catholic and they went to our church,” he recalled. “I was studying German and getting good at it. I realized if I could study German, I could study Spanish as well. That put me on the road to studying Spanish.”

Choosing journalism for a career, “as far back as 2001 I was attempting to do interviews in Spanish,” Connolly told Catholic News Service in a telephone interview from Memphis. “I kept returning to immigration as a topic over and over in my work at the Birmingham Post-Herald. I did a big project on Mexican immigration in Alabama. I was briefly with The Associated Press in Arkansas and briefly covered immigration in Arkansas and at The Commercial Appeal in Memphis,” where he currently works.

Connolly had lunch with an old friend from his parish who was by then the head of the Latino Memphis social service agency. “He was very concerned about immigrants’ kids. A lot of parents have children dropping out of school, getting into very negative things. That was in 2010. That’s what got me looking into immigrant children,” he said.

“Much of their potential is being lost due to dropping out of high school or college, or substandard academic achievement,” Connolly added. “Many Hispanic Catholics are going to see elements of their own lives reflected in the book. Those who are not Hispanic are going to find things that they didn’t know about the people they shake hands with the sign of peace every Sunday.”

PREVIOUS: Catholic groups urge physicians to support AMA code on assisted suicide

NEXT: Conference focuses on fostering church leadership roles for laywomen

Share this story