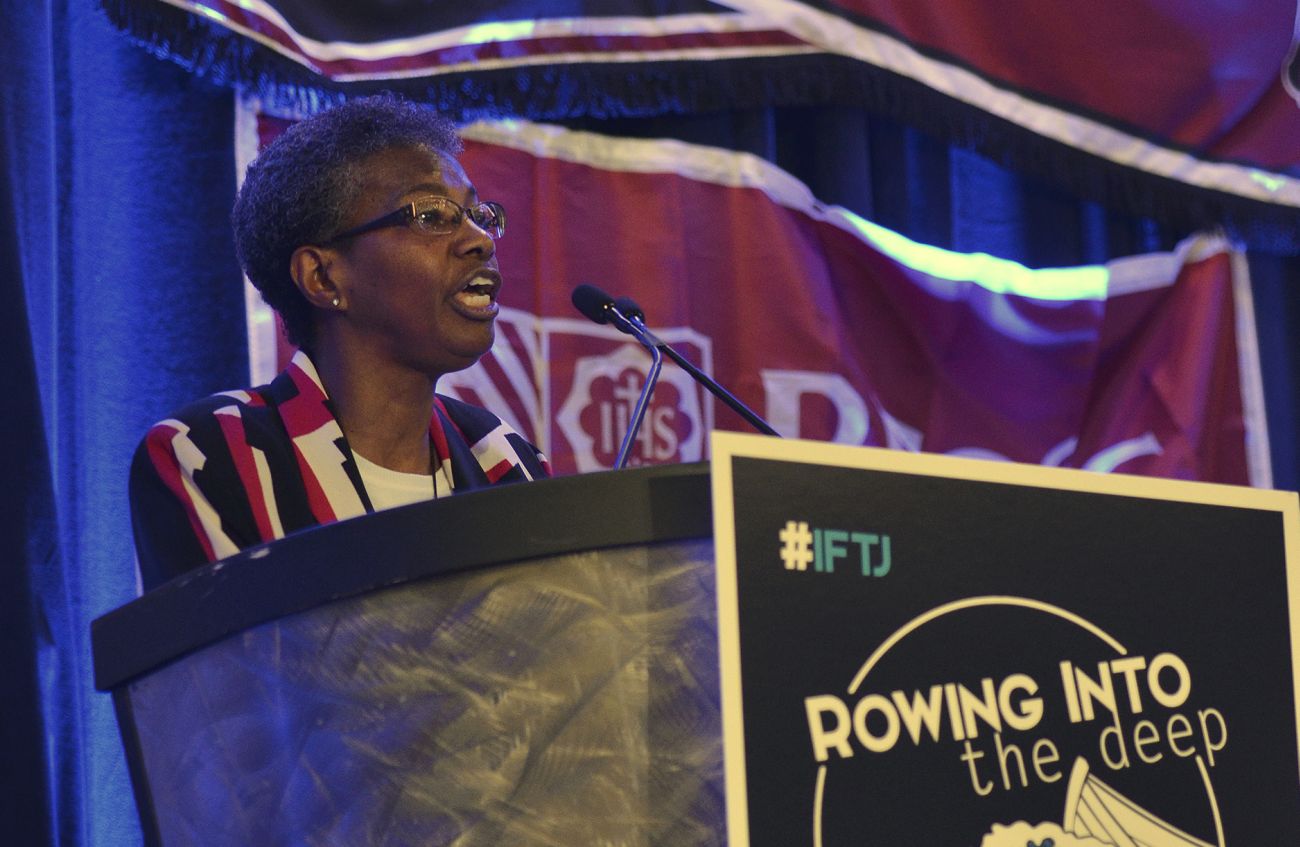

Sister Patricia Chappell, executive director of Pax Christi USA, speaks Nov. 5 to a crowd of more than 2,000 young adults at the Ignatian Family Teach-in for Justice held in the Washington suburb of Arlington, Va. She called racism “our national disease” and asked the group of students from Jesuit-run universities and high schools to educate themselves about injustices, past and present, analyze them, and do something to bring about peace and justice. (CNS photo/courtesy Ignatian Solidarity Network)

ARLINGTON, Va. (CNS) — Calling racism the country’s “national disease” and “our greatest injustice,” Catholic speakers at an annual gathering of young adults asked the group to call out injustice in order to heal the hurt and damage it has caused, not just in the country but in humanity.

“Racism in the U.S. is our greatest injustice, it has crippled all of us in the human community,” said Sister Patricia Chappell, executive director of Pax Christi USA, and one of two keynote speakers at the Ignatian Family Teach-in for Justice event that took place on the outskirts of Washington Nov. 4-6.

The annual event, attended by approximately 2,000 students from Jesuit-run high schools and universities in the U.S., focuses on social justice issues.

[hotblock]

“It is our national disease and in our collective DNA,” said Sister Chappell, a Sister of Notre Dame de Namur. “While getting sick was not our fault, getting well and healing together is our responsibility. Dismantling racism is something we must do together. Peacebuilding is something we must do together. We build two-way bridges to form the beloved community, not walls.”

Sister Chappell urged the young adults to learn about and analyze unjust systems and practices in the U.S. that too often and for too long have dealt an unfair hand to communities of color.

“There has never been an equal playing field in the legal system, the political system, the religious systems, the educational systems, the social service systems, the economic systems” in the country, said Sister Chappell.

She urged those in attendance to educate themselves about such injustices, past and present, analyze them and do something to bring about peace and justice.

The past couple of years have shown, she said, that “we have lived with myths and lies that had led us thinking that we were no longer a racist society.”

Father Bryan Massingale, professor of theological and social ethics at Fordham University in New York, addressed the group in a keynote speech Nov. 4.

He reminded the students that the class of 2018 had witnessed in their last four years the unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, numerous shootings of unarmed black men and boys, a presidential candidate who said Mexican people were rapists, and most recently white supremacist “marchers carrying tiki torches through an American street.”

“You have not seen these things in America, except in grainy black and white videos that your history teacher showed you,” he told his listeners, mostly in their late teens or early 20s.

[tower]

Father Massingale, author of “Racial Justice and the Catholic Church,” told the young adults that anyone of these events they have recently witnessed “would have been seismic, huge, but (with) all of them taken together, we are living in a time, dealing with increased racial tension polarization and division such that this country has not experienced in two generations.”

And recent studies show that the millennial generation, “the most diverse group of Americans that’s ever existed,” mirrors the division of modern American society, he said.

Talking about racial justice isn’t easy, he said, but he urged the group to have “an honest, adult conversation about race,” even if that makes some people uncomfortable, embarrassed, ashamed, fearful, angry, overwhelmed, helpless or paralyzed.

“That makes you normal,” the priest said.

Racism is an issue that “leaves us mute, tongue-tied,” he said, and one that “too often leaves us uncomfortable … embarrassed, limping.” And no one wants to deal with it until there is no choice, he remarked.

“What brings us here? Why do we begin our time together this weekend focused in on such a pressing, almost depressing, issue?” Father Massingale asked. “We must begin by looking at racism because racism is our most central justice challenge.

“No matter what issue you bring to the table,” he continued, “no matter what moves you personally, whether it’s health insurance, health care access, immigration, mass incarceration, educational disparity, living wages, poverty … every social justice challenge that faces us in the U.S. is entangled with, or exacerbated by racism against persons of color, African-Americans in particular.”

From educational access to immigration, environmental injustice to poverty, “if you don’t deal with race, you’re building a bridge to nowhere. You’re a path to futility,” he said.

Events such as the contaminated water in Flint, Michigan, a situation that began in 2014 and continues, are connected to race, he said.

“What happened in Flint would not have happened except because of the social vulnerabilities of the people (affected), because of the social, racial class to which they belong,” he said. “It wasn’t because public officials said, ‘Oh you’re black, we’re not going to take care of you.’ It’s something more insidious.”

He said it involves an “unconscious refusal to extend the same level of recognition and care to another that we would give to members of our own group because of pervasive cultural implicit bias.” That bias, the priest said, is based on how a person answers the question “who counts as we, who counts as us?”

Discussions about racism often are avoided, he said, because it makes some people uncomfortable, but for him as a person of faith, the issue must be dealt with.

“For me, as a believer, the reason why I’m concerned about racism is because racism is a soul sickness,” he said. “Racism is that interior disease, that warping of the human spirit that enables us to create a community where some matter and some do not.”

Much like Sister Chappell, who encouraged the young adults to step out of their zones of comfort and to study, Father Massingale talked about the “tragic testimony of the disease that has infected this country.”

This includes “the inhumane treatment of our African ancestors, the buying and selling of human beings,” he said. Facing what’s uncomfortable, he continued, can bring about change, including confronting “the lies that say some people are more important, less expendable and more valued, simply because they have less skin coloring.”

“But change does not happen alone and is more of relay race, he said.

“The goal is not for us to cross the finish line, enter into the racial promised land. The goal is to simply run the race and simply do our part so that we can pass the baton to those who come after us,” he said. “I’m running my race. It’s not for me to reach the finish line.

“It’s up to me to do what I’m supposed to do so I can hand the baton to someone else, to the 2,500 people who are in this room,” the priest said. “You are part of the relay race. We are not going to reach the finish line. You may not be the one who breaks the tape, but if you don’t run your race and do what you need to do, then we can’t win at all.”

Though the task may seem daunting, Father Massingale said, “I’m asking you to join me in the race to do your part. So that we can together create a new world.”

“As we go forth, we people who pursue racial justice, let us remember that social life is made by human beings. The society we live in is the result of human choices and decisions,” he said.

“That means that human beings can change things,” Father Massingale added. “You can change things. For what human beings break, divide, separate, we can — with God’s help — heal, unite and restore. What is now, does not have to be, and there lies our hope and our challenge.”

PREVIOUS: Porn, mental health are top challenges faced by collegians

NEXT: Dreamers top priority for Hispanic ministry directors during Hill visits

All of the speakers are of the liberal element . Very one sided. As a priest I will continue to remind people that its those one the left. Liberals-modernists and globalists that are the true people of hate and intolerance