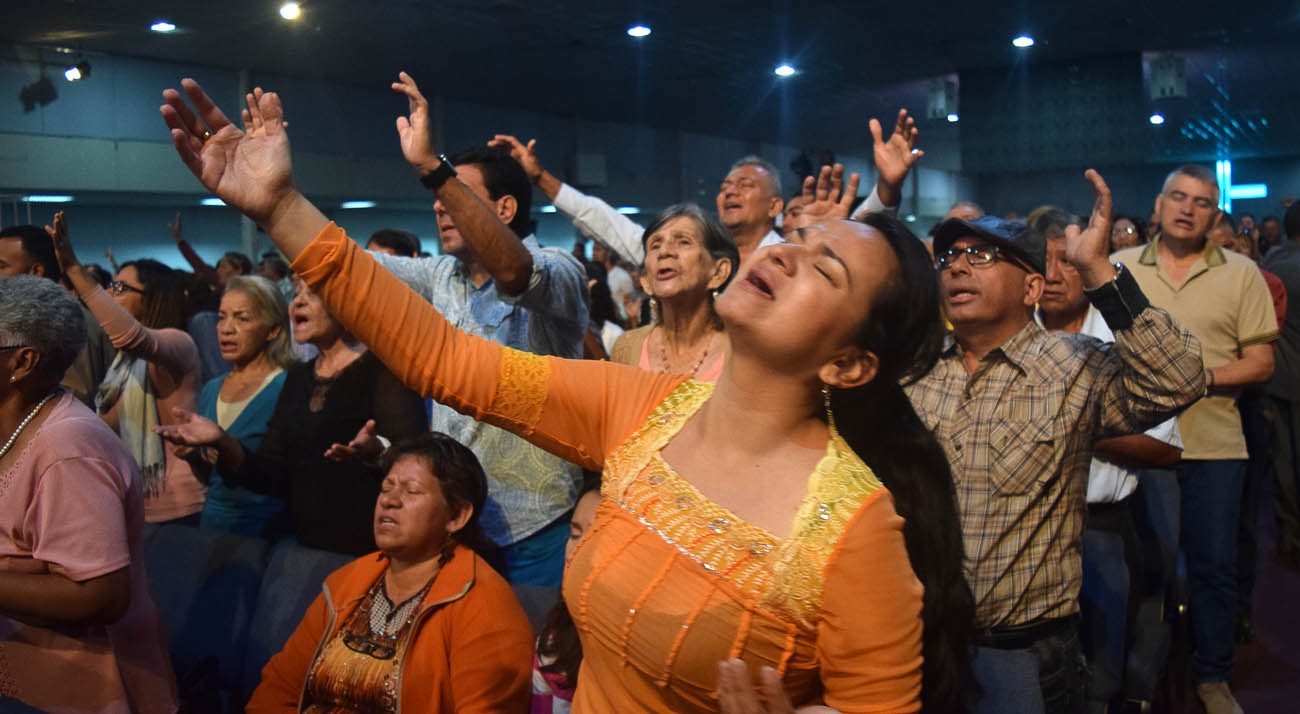

VALENCIA, Venezuela (CNS) — On a recent Sunday morning, Anderson Cedeno, 32, lifted his hands to the sky like the thousands around him, singing along to the lyrics projected on three massive screens overhead.

Some jumped with excitement. The choir swayed with the music. A drummer ripped off beats as if at a rock concert.

While it might sound like a typical Sunday service at a modern U.S. megachurch, the scene instead plays out weekly in the central Venezuelan town of Valencia and in evangelical churches across Latin America.

[hotblock]

Such evangelical churches have been gaining popularity for decades in the region as Catholic affiliation and influence has steadily declined. In at least three countries, Catholics have become religious minorities.

The numbers present a stark picture for the church: Whereas in 1910, 94 percent of the region identified as Catholic, in 2014 that number had dropped to 69 percent, according to figures from the Pew Research Center.

With their growing numbers, evangelicals also have increased their political influence, securing key mayorships and, in some countries, setting their eye on the presidency.

Cedeno, who grew up Catholic, said the evangelical services bring him “more happiness and tranquility” and have helped him turn from a life of alcohol abuse and “bad conduct” to “feeling the presence of God.”

That “psychological, personal and intimate” experience offered in evangelical sects is just one of many reasons such churches continue to attract more believers in the region, said Elvy Monzant, head of the department of justice and solidarity at CELAM, the Latin America bishops’ council.

He describes the trend as “worrying,” saying the congregations with the most growth often are “fanatical, spiritually evasive” and “focused on speaking in tongues, meaning sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference between faith and schizophrenia.”

[tower]

“These are often small churches, while a Catholic parish may include 30 separate communities and just one priest,” he said. “And for us Latin Americans, those relationships between priest and parishioner are important.”

Most analysts and church leaders quickly mention the priest shortage in the region as a key reason that many parishioners feel disconnected from their local church. In all of South America, more than 7,000 Catholics exist for each priest, according to CELAM.

But in no other part of the region has the evangelical wave been felt stronger than in Central America, where evangelicals have become majorities in both Nicaragua and Honduras. In other countries like Guatemala, 40 percent now identify as evangelical.

A population with a deep desire for religion, coupled with a shortage of priests, and in some cases a political history of anti-Catholic rhetoric created a perfect storm for the explosion in popularity for new evangelical congregations, said Guatemalan Bishop Rodolfo Valenzuela Nunez of Vera Paz-Coban.

“The bishops have recognized that one of the main causes of the growth of evangelicalism has been the result of the difficulty in growing the collective Catholic conscience,” he said.

As a result, the evangelical churches have filled an “underserved market,” said David Smilde, University of Tulane sociology professor, who extensively studied the trend in the 1990s and 2000s in Venezuela.

In the case of the megachurches with services that can feel like a well-produced TV program, churchgoers find an experience they feel is “healthy and good, but also interesting and fun,” he said.

His research also found that young men in Latin America, like Cedeno, find in evangelical churches a way to address the daily problems they face, such as substance abuse and marital problems.

As evangelicals have increased their numbers in the region, many of their leaders have set their sights on political power, often trumping their socially conservative values. An evangelical pastor nearly won the Costa Rican presidency in February by focusing his campaign on opposition to gay marriage. Evangelicals also have won important influence in the Brazilian legislature and the mayorship of Rio de Janeiro, one of Latin America’s largest cities.

In Venezuela, Javier Bertucci, former evangelical-pastor-turned-presidential-candidate, has attracted a rock-star like following and, while few expect he could beat incumbent President Nicolas Maduro in the May election, the enthusiasm behind his campaign has turned heads in the country’s political sphere.

When asked about his past as an evangelical pastor, Bertucci plays down his role, saying “over 90 percent of Venezuelans consider themselves Christian.” He said he hopes Venezuelans fed up with the current political climate will see him and his religion as a third way, not affiliated with traditional parties or the Catholic Church.

“Here people are disappointed with the traditional left and right,” he said.

But in some countries like Venezuela, where Pew Research numbers show 79 percent still consider themselves Catholic, evangelical congregations have grown at a much slower pace.

In Caracas, while Jesuit Father Alfredo Infante has seen evangelical congregations gain some popularity in his community, he said, “It’s not a centralized phenomenon.”

“The few sects that have grown, it’s because they’re a decentralized movement and don’t depend on so much hierarchy,” he said. “It’s more spontaneous and communities are constructed quickly.”

The church has attempted to respond to the declining numbers in several ways, including by placing new emphasis on missionary work, an area where the church had “lost its capacity,” according to Monzant.

“The church became too focused on the liturgical, sacramental sector, inside our buildings, and our flavor for missions was lost,” he said.

Monsant also insists that church leaders should continue to refocus on the region’s poorest and be a “church of the poor,” an idea often advocated by Pope Francis.

“We must accompany the poor in their daily struggles for their rights, attacking the structural causes of their poverty” he said.

He believes some countries in the region, such as Mexico and the Dominican Republic, have already started to show the results of those efforts. Catholics there have slightly grown in number in recent years.

The priest shortage has also eased. In Guatemala, the bishops’ conference reports priestly vocations have risen to levels “never seen before.”

“But the challenges also have grown,” Bishop Valenzuela added.

PREVIOUS: Philippine church groups launch network to support Australian nun

NEXT: Pope leads rosary for peace at Rome shrine

Share this story