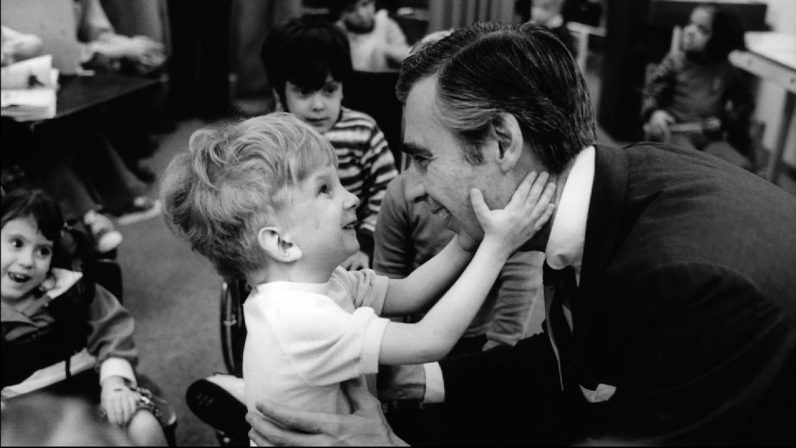

Fred Rogers, the much-loved children’s television figure, who died in 2003, is the subject of a new documentary, “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” (CNS photo/Jim Judkis, Focus Features)

NEW YORK (CNS) — First off, to answer everyone’s question about “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” (Focus), the cheerful and reverent documentary about Fred Rogers, creator and host of the PBS stalwart “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood”: Will it make you cry?

That’s too subjective an assessment for an easy answer. One’s reaction to the first half of the film will depend on the amount of interaction that you, or your children or siblings, had with his daily broadcasts on his original run from 1968 to 2001. (Reruns ended in 2008, five years after Rogers’ death).

In the closing half, though, director Morgan Neville skillfully re-enacts Rogers’ ritual in which he asked audiences, on public occasions, to take a few silent seconds to think of someone in their lives who had loved and helped them. If that doesn’t get you into a full-on soul-cleansing sob, you’re not only missing the entire point of the documentary, you should also get your empathy level checked.

[hotblock]

This film joins a growing list of tributes — book-length appreciations as well as articles — that together amount, in Catholic terms, to a movement for canonization, showing Rogers’ moral courage in the face of adversity from funding threats and indifference from the culture at large.

And to another universally asked question about the gentle, soft-spoken Rogers — was he that way in real life? — the answer, from his family and cast members, is an emphatic yes. What you saw and heard was who he was. The purity that came through the TV screen was authentic.

There are occasional mentions of Rogers’ spiritual life. As an ordained Presbyterian minister — a role he had long aimed to fill — he was given a special, and presumably unusual, charge to be involved in children’s TV. But in the interest of having as wide an audience as possible, he didn’t flaunt his Christian faith. He led by simple example.

So there are oblique references. His son John remarks, for example, that it wasn’t always easy “having the second Christ as my dad.”

Rogers delayed his entry into seminary in the early 1950s after registering his disgust that programming aimed at children was reduced to pie-throwing slapstick billed as entertainment. After some early work as a floor manager for NBC, he began “Children’s Corner” on Canadian TV, and his “Neighborhood” evolved from there.

His widow, Joanne, talks about the time, not long before her husband’s death from stomach cancer, when he’d been perusing the Bible and had focused on the Gospel of Matthew’s parable of the last judgment. It portrays Jesus, at his second coming, separating humanity into sheep for salvation and goats for damnation. Rogers asked his wife whether she thought he qualified as a sheep. She assured him he did.

[tower]

The TV host, based at WQED in Pittsburgh, was also trained in child psychology. He addressed children at the level of their simplest fears, and had anxieties of his own, expressed through his familiar puppets.

The tremulous and always questioning Daniel Striped Tiger — that was him. Yet the imperious King Friday XIII represented another part of his personality as well.

His favorite number, 143, which he said in numerological terms was “I love you,” also was his adult weight. Glimpses of Rogers as a chubby, frequently ill, youngster, his daily swimming routine and mentions of his vegetarian diet indicate the iron will that helped him achieve his slim physique — and suggest one of the sources of his compassion for bullied children.

Neville makes some faintly political points. The very first episode of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” for instance, had a plot in which King Friday of the Land of Make-Believe demanded that a wall should be built around his kingdom to keep out “all the people who are not like us.” Later, an interviewee observes that Rogers was a registered Republican all his life.

The documentary’s treatment of homosexuality, mainly in connection with one of Rogers’ associates, as well as its inclusion of a sight gag involving “mooning,” will raise doubts in parents’ minds about its suitability even for mature teens. They will have to weigh these problematic elements against the movie’s overall positive values and educational import.

Rogers’ greatest disappointment was his feeling that the power of a nationally broadcast TV program was fleeting, and couldn’t change a harsh culture of violence and intolerance. Neville includes sound clips of Fox News personalities complaining that Rogers created an entitled generation, and the picketing of his funeral by the extremist followers of the Westboro Baptist Church.

But the interviewees think Rogers would have responded to that with his customary kindness.

To the question asked of Jesus in the Gospel of Luke, “And who is my neighbor?” Rogers would likely have answered “All of you,” adding his signature closing line, “I like you just the way you are.”

If you’re in need of hearing that from him one more time, bring some tissues. A little robust bawling might do you a world of good.

The film contains a fleeting glimpse of rear male nudity and mature discussions of racism, homosexuality and death. The Catholic News Service classification is A-III — adults. The Motion Picture Association of America rating is PG-13 — parents strongly cautioned. Some material may be inappropriate for children under 13.

***

Jensen is a guest reviewer for Catholic News Service.

PREVIOUS: Fred Rogers’ ministry was on TV to kids, says documentarian

NEXT: Books on saints, secrets, Mary for your children’s summer reading

Thank you so much for the Catholic Philly. It’s a good thing to see each week. Keep up the good work!!!