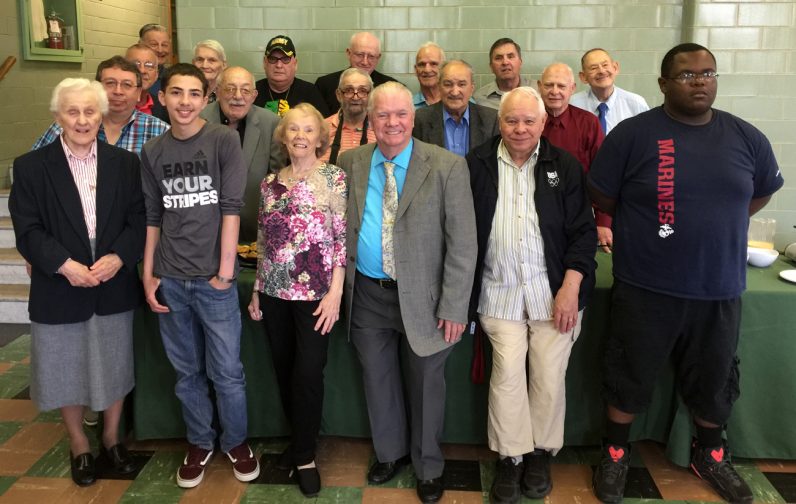

Attendees at a recent Mass and reunion of graduates of the former St. Francis Vocational School, and current residents of its successor St. Francis-St. Joseph Homes, pose for a photo, including long-time chaplain Trinitarian Sister Bernardine Schmalhofer (far left).

As memorial Masses go, the Mass held recently in the chapel of the Missionary Servants of the Most Blessed Trinity’s Generalate in Northeast Philadelphia was tiny — perhaps 20 or so mostly elderly men who more than 50 years ago attended St. Francis Vocational School, now a much smaller St. Francis-St. Joseph’s Home for Children.

Included in the group were a few spouses and current residents, and also Trinitarian Sister Bernardine Schmalhofer, a long-time chaplain for St. Francis; Frank White, a former staff member and Oblate of St. Francis de Sales Father Jim Dalton, a long-time friend of the group and celebrant of the Mass.

What makes the group most interesting is that they represent a child care system that no longer exists. It was a system where children often entered at birth and remained until they were deemed old enough to earn a living on their own.

[hotblock]

They were born before the era of Aid for Dependent Children, food stamps and other programs of the social safety net that enable today’s needy families, especially single parents, to raise their children at home.

For those who entered at birth in that past generation a first stop for Catholic children was usually St. Vincent’s Home in Lansdowne conducted by the Daughters of Charity. Girls might stay all the way through their school years.

Boys of school age were passed on to St. John’s Orphan Asylum in West Philadelphia, which was conducted by the Sisters of St. Joseph, and at age 11 or so passed either to St. Joseph Home for Boys in Philadelphia, which was conducted by the Holy Ghost Fathers or to St. Francis in Eddington, which was conducted by the Christian Brothers.

There they would remain until deemed ready to be on their own. St. Francis was founded in the 1880s by the three Drexel sisters, Elizabeth Smith, Katharine (now St. Katharine) and Louise Morrell. Originally established as a trade school for dependent boys, it was private charity. After the death of Louise Morrell in 1945, it became dependent on payments from the City of Philadelphia and other jurisdictions which remains the case to this day.

What was the experience of these children, born in poverty so long ago, and what did they do with their lives? Here are a few examples.

“I was a newborn when I went to St. Vincent’s,” said Mike Quaranto, who was born in 1939. “I then went to St. John’s and then to St. Francis. I was there for school from seventh grade through 10th grade then went to Father Judge High School for 11th grade.”

An early 1960s procession of Catholic leaders including Archbishop John Krol from the 19th century-era St. Francis Vocational School heads toward a new school on the campus in Eddington. (Courtesy the Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia)

However, while he was in 11th grade he turned 17 and the City of Philadelphia would no longer pay for him. Unless he had family willing to cover his costs he would have to leave.

“The court said they wouldn’t pay and a lot of us left,” he said.

Mike did have an aunt who took him in and he finished 11th grade at Father Judge and his senior year at Abington High School, which was closer to where he was living. After graduation he had difficulty finding work because the military draft was still on and employers were reluctant to hire anyone draft-eligible.

After a few moths he signed up for the Air Force. He remained there and ultimately retired with the rank of master sergeant, continued to work for the government until his full retirement. He also married, has three children and grandchildren. What were the institutions like for him?

“I was like any other kid and sometimes got in trouble,” he said. “If I got my butt kicked I deserved it. I loved St. Francis and had no problems. I always kept up with my friends and would even come down from Maguire Air Base for meetings.”

Ed Mockapetris, now 72, entered the system after his father’s death and mother’s illness. He entered in sixth grade and most of his high school years were at Father Judge.

“In my senior year I was in a transitional program and working at Horn & Hardart,” he said.

After leaving St. Francis he received a partial scholarship to La Salle College and even spent a college year in Switzerland. He also thought about possibly entering the seminary, but most of his career was in health care. He met his wife Angela through Epsilon Nu, which was a Catholic singles group, and they married in 1983.

As for St. Francis, “It gave me a sense of organization and direction,” he said. “It was a disciplined and ordered life. I was a daily communicant when I was there and continued to be for many years. I already had a deep love of Our Lord my parents taught me and that was enhanced at St. Francis.”

The procession reviews the new school building at St. Francis Vocational at its early 1960s dedication. (Courtesy the Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia)

Frank Forsyth, born in 1940, began life at St. Vincent’s Orphan Asylum, and continued on to St. John’s.

At St. John’s he was especially fond of Sister Francis. One day he did something he shouldn’t and she sternly told him to go into the next room for punishment.

He started to cry and in the next room after the door was shut she didn’t hit him but told him when she made a noise he should cry and when he left the room not to smile, so the other children would think he was punished.

At St. Francis his first prefect briefly was Brother Gratian of Mary who left for the Philippine missions and ultimately became a priest. As Father Gratian Murray he founded an orphanage in Bacolad, which was modeled somewhat on St. Francis. Now deceased, there has been a cause for canonization opened for Father Gratian.

In addition to academics Frank worked in the chicken yard because St. Francis still had a working farm at that time. When he turned 17 at St. Francis in the middle of the school year he was told he had to leave, but one of the benefactors of the school took him in.

After graduating from Father Judge Frank worked in a variety of fields but mostly in the trucking business. He traveled the country and he and his wife Dolores raised four kids.

“St. Francis gave me structure and taught me not to be afraid to try anything I wanted, to be independent,” he said. “I was a jack of all trades.”

[tower]

Richard Powers was born in 1940 in Reading, which was then part of the Philadelphia Archdiocese. Because he was Catholic he was sent to St. Vincent’s where he was happy. He remembers crying on the day he was told he was leaving for St. John’s, but it all worked out.

Finally, at St. Francis he was placed in a vocational program and worked on the farm. When he aged out he was allowed to stay as a worker with a small stipend. After a few months he left and hitch-hiked back to Reading where he got a dishwashing job. Over the years he worked in many fields but mostly in trucking.

As a young man he also considered religious life and joined the Oblates of St. Francis de Sales as a lay brother. Although he left after nine years his Oblate friendships remain. It is through him Father Dalton has become a supporter of the Friends of St. Francis.

As for what he got out of St. Francis, it was “the value of serving other people,” Richard said. In keeping with this in retirement he remains active as a volunteer driver for Meals on Wheels.

Interestingly, while the courts in that era would not approve payment for boys after they reached 17 that was not the case for girls, who were allowed to stay through high school.

Pat Lufkin never attended St. Francis but she was a resident of St. Vincent’s. “I was 13 in 1947 and we lived in St. Richard Parish in South Philadelphia when my family broke up,” she said. “I and two sisters went to St. Vincent and my two brothers went to St. Joseph’s.”

While at St. Vincent’s she got to complete her high school years at West Catholic High School for Girls and graduated in 1951. She went on to a secretarial career, married and became the mother of five.

As for her experience in Catholic child care, she would rather it had not happened, but “it was a good experience,” she said.

Actually there were thousands of children in residential child care through the Archdiocese of Philadelphia in that era. Even if they never mention it, most of them became hard-working, solid citizens, which is exactly what was supposed to happen.

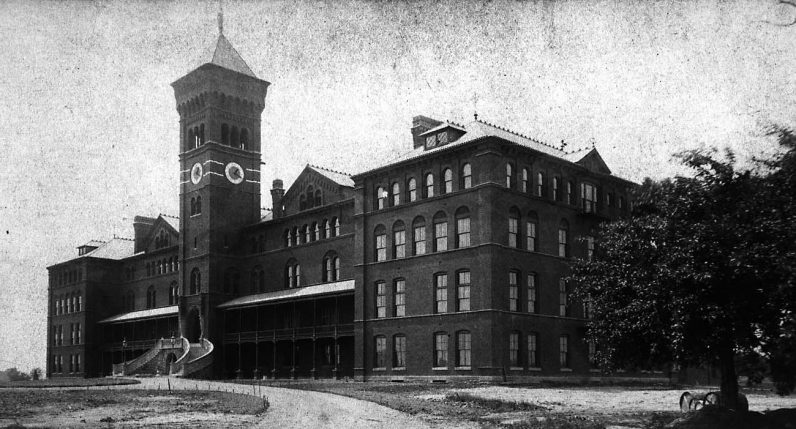

St. Francis Vocational School in Eddington as it appeared in 1889. (Courtesy the Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia)

PREVIOUS: Dominican Sisters-run home for dying patients to shut it doors

NEXT: Phoenixville parish fundraiser pairs BBQ cook-off with craft beers

Share this story