HUIXTLA, Mexico (CNS) — Members of St. Francis of Assisi Parish in this southern Mexican city rose early Oct. 24 to feed but a fraction of the Central American migrants traveling in a caravan, which is trying to traverse Mexico and reach the United States border.

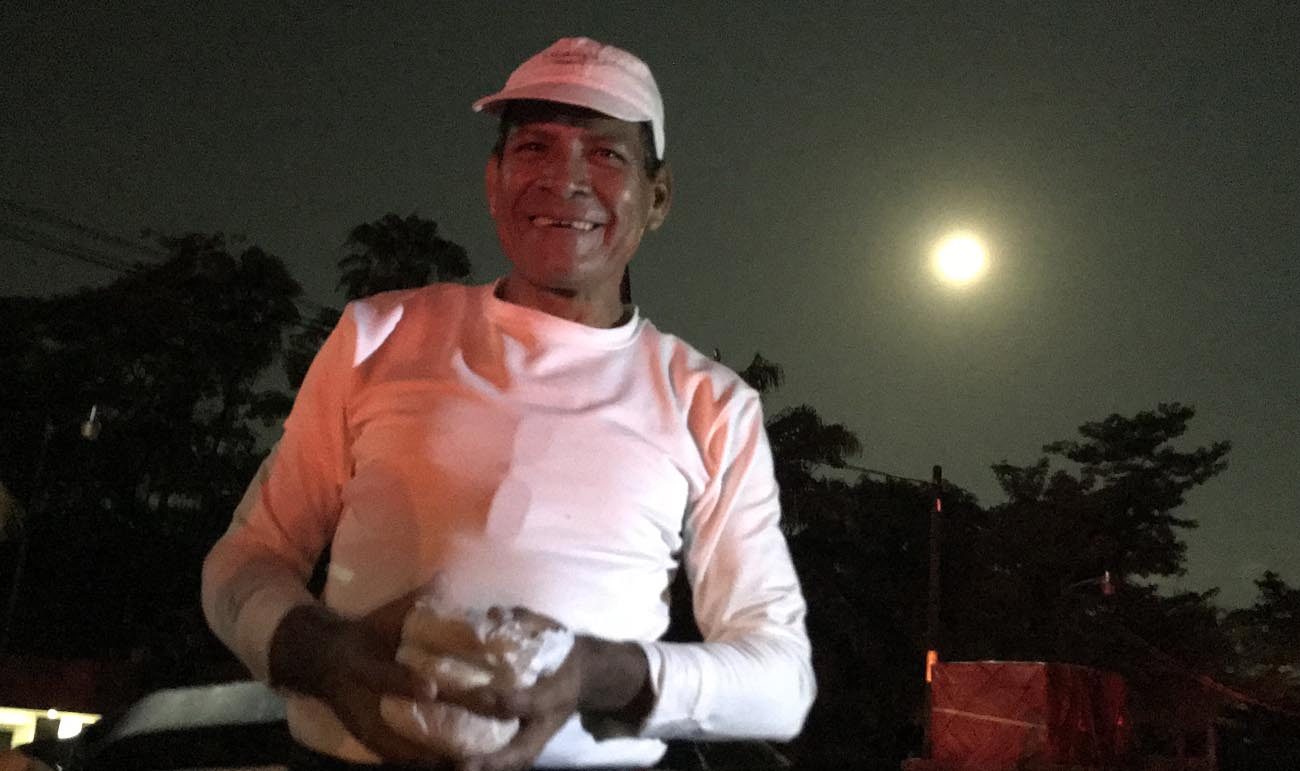

“Tortas! Take one. The road ahead is long,” Rafael Gomez yelled from the bed of a white pickup to the passing migrants as they streamed out of town in the predawn hours. They had slept in the streets in what resembled an impromptu refugee camp.

“God bless you,” the grateful recipients responded as they took the ham sandwiches and head for Mapastepec 40 miles ahead.

[hotblock]

The caravan left Honduras Oct. 13 and has swelled to at least 4,500 participants, according to the Mexican government.

Nearly 1,700 people already have requested asylum in the country, but most of the migrants interviewed told Catholic News Service they want to arrive in the U.S., where an uncertain welcome awaits.

Catholics working with migrants describe the caravan as the response to a desperate situation in Central America’s northern triangle — Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador — as poverty, violence and drought push people to risk the treacherous road through Mexico. Political unrest and the persecution of anti-government protesters in Nicaragua have sent even more people fleeing with some joining in the caravan.

The problem, however, is especially acute in Honduras as prices rise, salaries stagnate and gangs prey on populations. Many Hondurans report being charged “war taxes,” or extortion, to live in their own homes.

“This is an indignant reality caused by the current situation in our country,” the Honduras bishops’ conference said in an Oct. 20 statement on the caravan.

“It’s forcing a determined group to leave behind what little they have, risking themselves without any certainty on the migrant route toward the United States, with the desire of reaching the promised ‘American dream,’ which would allow them to resolve their economic problems, improve their living conditions and, in many cases, preserve their physical safety,” the bishops said.

[tower]

They bitterly noted, however, the country has come to depend on remittances as Hondurans in the U.S. supported family members back home.

“We have preferred to be happy with remittances as a solution to our internal problems. What’s new about this caravan is the massive way thousands of people, the majority young, are going with the hope obtaining sufficient resources to transform Honduras,” the bishops said.

The origins of the caravan remain murky, but the migrants marching through Mexico said they either saw news reports, social media postings or heard rumors about it. Many thought it was a way to find safety in numbers as they headed north. Criminal gangs and crooked cops in Mexico often prey on small groups of migrants.

The caravan has captured widespread international attention. It also has caused controversy in the U.S. as President Donald Trump has tweeted his displeasure. Trump has threatened to cut foreign aid to Central American countries in retaliation and adamantly stated the migrants will not enter the U.S.

Governments in Guatemala and Mexico have tried to impede the caravan.

Mexico closed its end of the bridge at its border with Guatemala, prompting migrants to swim and raft across the Suchiate River, which separates the two nations.

Mexico also sent two planeloads of Federal Police officers to its southern border, but the caravan pushed past them.

“Their hands are tied,” Huixtla Mayor Jose Luis Laparra Calderon said of the Federal Police. He pointed to the presence of foreign journalists and human rights groups for preventing the Federal Police from taking a heavy-handed response.

Caravan participants act unfazed in the face of Trump’s threats and expressed hope that he has a change of heart or a higher power intervenes. Almost all shared fears of being returned.

“We don’t want to return to Honduras after all of this effort to get here. We only want to live a better life,” said Elias Ruiz, 21, a construction worker who fled San Pedro Sula after being unable to support his wife and infant son.

Ruiz hit the road after having to pay tattooed gangsters the war tax. Work also was spotty and he couldn’t make ends meet.

“If you don’t pay them, they’ll kill you,” he said of the gangs. “They say, ‘We’ll make an example of you.’ The example is they kill you.”

Upon decamping Huixtla, the caravan slowly snaked along the coastal plain of Chiapas state under scorching temperatures. People walked until they were tired, then hitchhiked, hopping aboard pickups, dump trucks and tractor trailers. People even pushed strollers with infants and carried toddlers on their shoulders.

Chiapas is Mexico’s poorest state, but people along the route shared bottles of water, bunches of bananas and surplus clothing and cushions with the passing throngs.

Parishes in the Diocese of Tapachula have collect supplies for the caravan and fed its hungry participants, with the parish in Huixtla distributing 3,000 tamales and other provisions. Karime Alejandro Garcia, 19, and Dana de los Santos, 17, brought bags of clothes collected at St. Bartholomew Parish to the highway as the caravan passed the town of Villa Comaltitlan.

“Every barrio was collaborating as it could, some collected clothes, others water, food,” Alejandro said. “Little by little we’re working to have something we could give our brothers.”

“As a diocese, we’re trying to accompany, as the Holy Father says, care for and protect migrants,” Father Cesar Canaveral, diocesan migrant ministry director, said. “Unfortunately, we don’t have a government that is responding to the needs of this caravan.”

PREVIOUS: Bishops, young people walk to St. Peter’s on pilgrimage of faith

NEXT: South Korea grants refugee status to Iranian student who became Catholic

Share this story