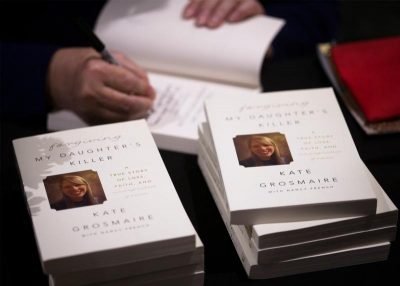

Kate Grosmaire of Tallahassee, Fla., signs a book for an attendee after a discussion of approaches to criminal justice that promote human dignity Nov. 5 at the St. John Paul II National Shrine in Washington. Leading the discussion were Kate and her husband, Deacon Andy Grosmaire. (CNS photo/Tyler Orsburn)

WASHINGTON (CNS) — What could have been another senseless murder in a society with too many of them already was transformed into restorative justice for the killer and healing for the victim’s parents.

Kate Grosmaire and her husband, Andy, then in deacon formation, had been to Palm Sunday Mass at their parish in Pensacola, Florida, in 2010 and returned home to work in their garden. They heard the doorbell ring — an unusual occurrence in their neighborhood, Kate recalled in a Nov. 5 presentation sponsored by the Catholic Mobilizing Network, which advocates for restorative justice and an end to the death penalty.

At the door was a victim’s assistance coordinator and a county sheriff’s deputy with the grim news: “Your daughter’s been shot.” Ann Grosmaire was just 19 years old. Kate said their first impulse was to get in touch with her boyfriend, Conor McBride, to tell him the news. Then came the gut punch: “Conor’s the one who shot her.”

What followed was a Holy Week unlike any the Grosmaires or their parish had ever experienced. Ann lay in a hospital in grave condition while her parents grieved. “It’s a miracle she’s alive,” one doctor had told them. “We didn’t see the miracle,” Kate said, although in hindsight, noted Andy, now a permanent deacon in the Diocese of Pensacola-Tallahassee, “we got to say our goodbyes to her.”

[hotblock]

Unexpected moments of grace took place. “I saw a spontaneous rosary outside” the hospital, Deacon Grosmaire remembered. Realizing they needed cat litter, the Grosmaires told someone and by the time they returned home one night, 40 pounds of it had been put on their front porch. Another day, four clergy stopped by to visit, one after the other, none of them acting in concert with each other.

Most surprising of all: Everyone in jail gets to select four people who can visit them. Conor McBride put Kate Grosmaire’s name on his list.

Kate, who was part of her parish’s healing ministry, was preparing to tell McBride that she loved him and forgave him. “What do you want me to tell him for you?” she asked her husband. Deacon Grosmaire said he had “heard” Ann telling him, “Forgive him, forgive him” — an instruction he was prepared to brush off like so many favors teenagers seek from their parents.

Later, though, Deacon Grosmaire saw a vision of Jesus next to Ann in the bed, which he interpreted as a sign that Ann was going to be with Jesus in heaven. He relented. “Tell him I love him, too,” Deacon Grosmaire told his wife.

When the respirator keeping Ann alive was turned off — on Good Friday, at 3 p.m. — the next stage began.

The Grosmaires said the state’s attorney explained to them that “we wouldn’t have to do anything,” Kate said, as the judge would offer a jury a choice of first- or second-degree murder. The attorney, Paul Campbell, said until the case reached the court, his office had “flexibility,” including filing manslaughter charges that could net a five-year prison sentence.

[tower]

Although Campbell offered that as a hypothetical outcome, the Grosmaires seized on the possibility, but didn’t know how to articulate it until an Episcopalian minister pointed to restorative justice as a possibility. “You Catholics are all about restorative justice,” he told them.

Restorative justice asks three basic questions, according to Caitlin Morneau, director of restorative justice for the Catholic Mobilizing Network: “What harm was done? Who was harmed? How can we as a community work to repair the harm as best as possible?”

It took a lot of doing, but the Grosmaires persuaded Campbell to conduct a restorative justice circle in which McBride, his parents, the Grosmaires, the state’s attorney and the judge would all participate to come up with a sentence acceptable to all, another tenet of restorative justice. The Grosmaires insisted McBride not be brought to the circle in shackles, as was jail policy — a request allowed by the jail.

It took time to prepare all the participants; it was 14 months after the shooting before the circle was convened. “It was the first time restorative justice was ever tried in Florida for a capital crime — and maybe in the whole nation,” Kate Grosmaire said.

It was then that the Grosmaires heard the circumstances behind the shooting.

Ann and McBride, himself only 20, had been arguing as of late. That morning was another fight. “It blew up into a breakup fight,” Deacon Grosmaire said. “Conor said he couldn’t go on like this, so he went back into the house to get his father’s shotgun. He was going to shoot himself.” Ann, who had gotten into her car, “followed him back into the house,” he added. McBride turned and fired one shot through one of Ann’s eyes. “He was immediately sorry for what he did and called the police.”

Hearing the story was “the one time I physically hurt,” Deacon Grosmaire told Catholic News Service after the talk at the St. John Paul II Shrine.

In the circle, Deacon Grosmaire said Michael McBride, Conor’s father, made a revelation of his own: “It’s my fault. I’ve been angry for five years (after a brother of Conor’s had died), and I made Conor angry, too.”

“Paul Campbell said he would never have thought about talking to the McBrides at all,” said Kate Grosmaire, who, two years ago, put their family story into words in the book “Forgiving My Daughter’s Killer: A True Story of Loss, Faith and Unexpected Grace.”

What, the judge asked, would be a just sentence? Kate suggested five to 10 years in prison, plus 10 years of probation. Deacon Grosmaire suggested 10-15 years plus 10 of probation. The McBrides said, “We agree with them.” “I don’t know how they could,” the deacon said, “because we couldn’t agree with each other.”

Campbell recommended, and the judge accepted, a prison term of 20 years and 10 years’ probation, plus other conditions stipulated by the Grosmaires: taking anger management classes (McBride did so); talking about relationship violence (McBride made a public service announcement on the subject); and McBride committing to work on the issues closest to their daughter Ann’s heart that she would have pursued had she lived.

“We didn’t push for a lighter sentence,” Kate Grosmaire said. “We wanted to push for a more meaningful sentence.”

Deacon Grosmaire told CNS there is “both” the feeling of pain of having to relive Ann’s murder with each talk and a feeling of release when talking about it. The couple underwent counseling; “more than 90 percent of couples divorce after a child dies,” he said.

There is room for more restorative justice efforts, Deacon Grosmaire added. With Florida’s tendency to put more prisons in its rural panhandle to create more jobs in the region, he said, “we’ve got more prisoners than Catholics” in the diocese, where Catholics number 65,211.

PREVIOUS: National Review Board chairman seeks fix to address charter ‘loophole’

NEXT: Poor Handmaids’ foundress called model of living out love of God, neighbor

Share this story