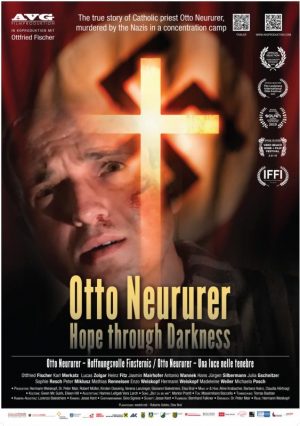

The movie poster for “Otto Neururer: Hope through Darkness” shows the actor who portrays the priest killed in a Nazi concentration camp during World War II. (CNS photo/AVG Film Production)

DUBUQUE, Iowa (CNS) — The film “Otto Neururer: Hope through Darkness,” based on the life of the first Austrian priest killed in a Nazi concentration camp, had its world premiere recently in Iowa.

The film, which recounts the true story of Blessed Neururer, was screened April 24-26 at the Julien Dubuque International Film Festival in Dubuque. Austrian filmmaker Hermann Weiskopf, who produced and directed the work with German co-producer Ottfried Fischer, was on hand for the first screenings.

His company, AVG Film Production, is known for creating historical dramas from World War II based on the lives of real people. A previous film, “Shattered,” told the story of Richard Berger, a Jewish leader in Innsbruck, Austria, who, in 1938, was also killed by the Nazis. Weiskopf and his team believe it’s important to spread inspirational local history from that era through film.

“We are talking about little positive heroes, who maybe didn’t change history, but certainly many hearts,” he said. “People get tremendously touched when they see our stories.”

Weiskopf, who spent about a decade working in the Italian film industry before returning to his hometown of Innsbruck, is looking forward to a June 4 showing of “Otto Neururer” at the Vatican.

“We will have this very exclusive screening there and on the list of people attending is the pope,” he said.

[hotblock]

Blessed Neururer grew up in the town of Piller, not far from Innsbruck, and did most of his ministry as a priest in the Austrian state of Tyrol. After refusing to marry a young woman to a fanatical Nazi official many years her senior and advocating for respect for the Jewish people from the pulpit, the priest was sent to Dachau concentration camp near Munich. He was later sent to Buchenwald, near the town of Weimar.

While in captivity he continued to do pastoral ministry, which was forbidden. He was executed in 1940 for performing a baptism on another prisoner. He was killed after being strung up by his feet for 36 hours. In 1996, Father Neururer was beatified by St. John Paul II.

Weiskopf and his team filmed in the church where the priest served and constructed a set that portrays the concentration camps.

The film opens with scenes showing Heinz Fitz, an actor in his twilight years, living in present day Austria. He has been unable to pray because of guilt associated with the despicable acts his father committed as a member of the Nazi Party. He is juxtaposed with Father Neururer praying while being tortured as a prisoner.

While feeding chickens, Fitz reflects on his life, saying “I’m a good man, that’s what most people think of me, but it’s a lie.”

Hermann Weiskopf, the Austrian filmmaker who directed “Otto Neururer: Hope through Darkness,” is shown April 26, 2019, at the Julien Dubuque International Film Festival. (CNS photo/Dan Russo, The Witness)

A flashback then shows the viewer the priest being beaten in a camp in Germany over 70 years before. An interrogator demands he reveal what another prisoner told him during the sacrament of reconciliation or be killed.

“The seal of confession is sacred,” says Father Neururer. “It can never be broken. … I would so much like to live. But a life without God is like an oak tree without roots. A puff of wind and it’s blown away.”

Over the course of the film, Fitz, with accompaniment from a local parish priest undergoing his own trial, and a young woman who acts as their driver, goes on a road trip to find out more about Father Neururer. In the process, Fitz wants to heal his shame and find peace.

Weiskopf also plays the role of Heinz Fitz’s father in the film. He shares screen time with his own son, Enzo, who plays Heinz Fitz as a boy. Weiskopf said he was personally affected during the making of the film by Blessed Neururer’s example of faith and love in the face of suffering and hatred. He hopes the priest’s story will have a beneficial impact on others.

“From the very beginning (in making the film), sometimes one could think that Mr. Otto Neururer is watching down and takes care that all the things go the right way,” said the director. “I got, a little bit, that feeling.”

***

Russo is editor of the Witness, newspaper of the Archdiocese of Dubuque.

PREVIOUS: Catholic officials pleased with new conscience protection rule

NEXT: As execution looms, case for clemency hinges on an act of forgiveness

Share this story