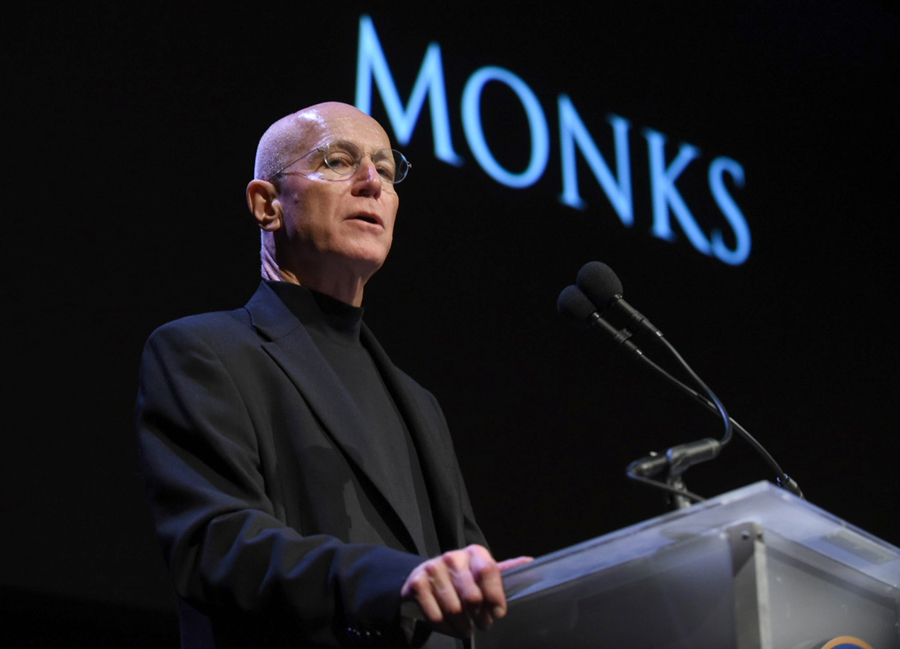

Benedictine Father Columba Stewart of St. John’s Abbey and University in Collegeville, Minn., delivers the 2019 National Endowment for the Humanities Jefferson Lecture in Washington Oct. 7, 2019. He talked about the effort begun in 1964 by Benedictine Father Oliver Kapsner to collect and copy millions of pages of sacred manuscripts. Father Stewart said the priest, spurred by the global political tension of the Cold War, feared the religious order’s heritage “would be vaporized if there were a World War III.” (CNS photo/Steve Barrett, courtesy NEH)

WASHINGTON (CNS) — It was the global political tension of the Cold War that prompted the collection and copying of millions of pages of sacred manuscripts, a project now being led by Benedictine Father Columba Stewart at St. John’s Abbey and University in Collegeville, Minnesota.

The Benedictine priest who started the effort in 1964, Father Oliver Kapsner, “feared that European Benedictine heritage would be vaporized if there were a World War III,” said Father Stewart in delivering the 2019 Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities Oct. 7 at a packed theater in downtown Washington.

“Monte Cassino in Italy, the mother abbey of Benedictines, had been totally destroyed in 1944. A nuclear war would be far more devastating,” Father Stewart said in his address, “Cultural Heritage Present and Future: A Benedictine Monk’s Long View.”

[hotblock]

“There was not anything we monks in Minnesota could do to protect the churches and cloisters,” he said, “but we could microfilm their manuscripts and keep a backup copy in the United States.”

Father Kapsner met with resistance from nearly all of Europe’s Benedictines — until he arrived in Austria. “Austria was one of the few countries in Europe where monastic libraries had not been seized during the Reformation or the French Revolution and its aftermath,” Father Stewart said.

The work was modeled after a Vatican effort in the 1950s in which many of its prized manuscripts were microfilmed and stored in the United States at St. Louis University.

“The scope of the work soon widened to libraries of other religious orders, then to universities and national libraries. The pace was swift, and the result by the end of the 20th century was a film archive of almost 85,000 Western manuscripts,” Father Stewart said.

However, as the Cold War fizzled out, hot wars sprang up — often in countries where the Benedictines’ efforts had spread. One country, Ethiopia, didn’t bother to wait for an end to the Cold War, which lasted from 1946 to 1991. Communist-affiliated rebels deposed Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974, plunging the nation into a decade and a half of political and military fighting and a nationwide famine.

“What had begun as a kind of archaeological expedition to discover ancient texts became a rescue project to preserve manuscripts in a nation convulsed by political upheaval and then a civil war,” Father Stewart said. “The cameras kept going, working throughout the 1970s, 1980s and into the early 1990s. In the end, 9,000 manuscripts were microfilmed,” funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, which sponsored the priest’s talk.

At the request of Orthodox Christians in Lebanon, who were trying to find anew their manuscripts — which had been scattered after decades of civil war — “we launched a project in northern Lebanon in April 2003, at the very same moment that American ground forces were approaching Baghdad” in nearby Iraq, Father Stewart said. “Lebanon had settled down; Iraq was heating up; no one could anticipate what would come next.”

[tower]

As the work of the Benedictines’ Hill Museum and Manuscript Library expanded in Lebanon, “we extended the project to Syria, forming partnerships with several church leaders in Aleppo, as well as in Homs and Damascus. Things were going well, and we even found a partner in Iraq,” Father Stewart noted.

“But then in 2011, Syria began to unravel as the spirit of the Arab Spring spread across the region. Three years later came the conquest by ISIS of much of Northern Iraq, driving tens of thousands of Christians and Yazidis from Mosul and the villages of the Ninevah plain.”

He added, “Through it all, our local partners kept photographing manuscripts as best they could, while collections were moved, hidden and in some cases destroyed. For too many of those manuscripts, all that remains are the digital images and perhaps a few charred pages.

The “human toll,” Father Stewart said, “upon our friends and colleagues was immense. In 2013, the Syriac Orthodox metropolitan of Aleppo, Mor Gregorios Yuhanna Ibrahim, was kidnapped along with his Greek Orthodox counterpart, Metropolitan Boulos Yazigi. They were never heard from again.”

Not long after Father Stewart began the effort of digitizing ancient Muslim texts in Jerusalem, he launched a similar project in Timbuktu, Mali. Within a couple of years, though, “Timbuktu was occupied for several months, its shrines to Muslim saints destroyed, its superb music silenced, the tourist trade on which it depended for economic survival extinguished,” he said.

“Early reports suggesting that its manuscripts had been burned proved to be incorrect; only a few manuscripts left behind as a false trail had been destroyed. All of the others were safe, whether moved to Bamako (the capital), or hidden in Timbuktu by families who had protected their manuscripts from Moroccan invaders, French imperialists, and other threats.”

Timbuktu was where Father Stewart was too close for comfort during a 2017 attack at a United Nations post in the city. He and several others were holed up in their hotel rooms for hours until rescued by Swedish soldiers attached to the U.N. military mission there.

The incident, he said, served as “a reminder that the people who live in such places are constantly exposed to such attacks: They don’t just fly in and out, they don’t have U.N. forces to spirit them away to safety.”

They, and their cultural heritage as it exists in manuscript, song, textiles, in whatever form, are always at risk,” the priest said. “Our efforts to help them, and the occasional inconveniences we experience, are the completely inadequate least we can do.”

PREVIOUS: Benedictine estimates 70 million-plus pages of manuscripts digitized

NEXT: Compensation plan for abuse victims opens in Colorado

Share this story