WASHINGTON (CNS) — The year 1980 was a bloody one for tiny El Salvador. In the early months of that year, Archbishop Oscar Romero of San Salvador, who had seen and heard of the disappearances an

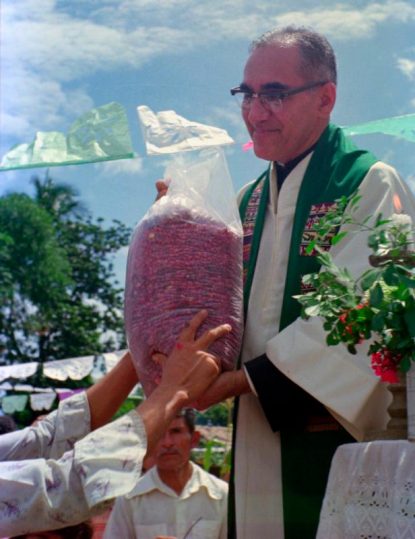

St. Oscar Romero is pictured inside a church at San Antonio Los Ranchos in Chalatenango, El Salvador, in 1979. (CNS photo/Octavio Duran)

d killings of civilians, was doing everything possible to avert a full-fledged war.

In February, the archbishop wrote a letter to then-U.S. President Jimmy Carter to say he was alarmed by the news of the U.S. sending more military aid as well as training repressive government forces of El Salvador. Those forces had been involved in the killings of citizens, including Catholic clergy and their parishioners.

He told Carter that if he really wanted to help, he shouldn’t send any such aid, nor intervene in the affairs of the country, nor support a military “without scruples,” one only interested in the repression of Salvadorans and “favoring the interests of the Salvadoran oligarchy.”

Archbishop Romero also had negotiated with the leader of a military coup that had taken over the government, urging him to put a stop to gunfire terrorizing a neighborhood near the National University in San Salvador. Finally, he called on soldiers not to follow orders “against the law of God” and to stop killing their brothers and sisters.

[hotblock]

Things seemed as if they couldn’t get worse. And then they did.

As he celebrated a memorial Mass for the mother of a friend March 24, 1980, the archbishop became the most famous victim of the more than 70,000 dead the war would produce over the next 12 years. By the end of 1980, four U.S. Catholic churchwomen would add their names that roster, dying as violently as Salvadorans.

As the church in El Salvador and others around the world observe the 40th anniversary of St. Romero’s martyrdom in March, the role church teaching played in his closeness to the poor has come into sharper focus.

And now St. Romero, canonized in 2018, has become a model for those championing social justice, highlighting the role of the Catholic Church when it comes to defending human rights.

Even back then, others understood this role. Leadership of the U.S. Catholic bishops, along with thousands of members of the U.S. Catholic Church, backed Archbishop Romero and constantly spoke against U.S. military funding for El Salvador, lobbied lawmakers to defend human rights and demonstrated in the streets, including in Washington, making known their opposition to U.S. taxpayer money that paid for forces that terrorized the innocent and produced massacres.

According to a Nov. 10, 1980, Catholic News Service story, Bishop Thomas Kelly, former general secretary of what was then the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, carried on with the message of Archbishop Romero after the Salvadoran’s death, telling U.S. Catholic groups and media that the war had added yet another burden to the poor of El Salvador and had resulted in the deaths of peasants, laborers and teachers.

St. Oscar Romero receives a sack of beans from parishioners following Mass outside of a church in San Antonio Los Ranchos in Chalatenango, El Salvador, in 1979. (CNS photo/Octavio Duran)

“Violence visited almost daily upon the poor and suffering people of El Salvador is an ever-growing source of grief to us,” Bishop Kelly said. “The church has shared fully in the suffering; it has made unmistakably clear its preferential option for the poor … accompanying the people in their hope, struggle and suffering. It has paid dearly for this commitment.”

By the time the war ended in 1992 with peace accords, the Catholic Church of El Salvador, along with the U.S. and Italy, would share in the death of four women religious, 16 priests, a seminarian, two bishops (including Archbishop Romero), and an untold number of catechists, pastoral agents and parishioners.

[tower]

Like his counterparts in the U.S., Archbishop Romero was moved to speak and act not by ideology, but by Catholic Church teaching that came out of two meetings in Latin America. Though he was slow to warm up to the 1962-65 Second Vatican Council, he was influenced by the adaptation of documents from the council produced in Latin America, which, in gatherings of bishops of the region, became focused on social justice.

The first such gathering took place in Medellin, Colombia, in 1968, and a second meeting took place in Puebla, Mexico, in 1979.

“If we cast our eyes over Latin America, what spectacle confronts us? It is not necessary to probe deeply. The evident truth is that the gap is constantly increasing between ‘the many who have little and the few who have much,'” the bishops wrote in a document issued after the Puebla gathering, where Archbishop Romero was in attendance.

“We invite all, without distinction of class, to accept and take up the cause of the poor, as it they were accepting and taking up their own causes, the very cause of Jesus Christ,” the document said.

What the Latin American bishops produced was a message by the church committing itself to the poor, upholding their human rights and liberation.

But the liberation they spoke of was not an ideological one. It came from a religious perspective. In the 1970s, peasants who worked with Archbishop Romero’s contemporary, Salvadoran Jesuit Father Rutilio Grande, experienced it. They spoke of the religious prism the priest used to frame their social condition. He had them read the story of the “people of God” in the Book of Exodus. They read how the people of God suffered hunger, mistreatment, oppression, until one day, they were liberated.

It was no different than the reality many were experiencing as citizens of nations with repressive military regimes that had engulfed Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s, including the one that was carrying out acts of terror against them in El Salvador in Archbishop Romero’s time. Like Moses in the Bible, the church and its leaders had a role to play in that liberation.

But it was one not welcome by the oligarchy, including members who were Catholic. One of them, Roberto D’Aubuisson, is said to have ordered the killing of the archbishop.

In his 2017 pastoral letter honoring El Salvador’s martyrs, Archbishop Jose Luis Escobar Alas of San Salvador explained that because church teaching denounced poverty, its consequences, causes and its aftermath in a more profound manner than before, the “Cains of the world,” in other words, the rich of Latin America who were oppressing others, “felt questioned,” and the church’s “option for the poor” became a source of aggravation for them.

Their complaints and recrimination against church leaders such as St. Romero took on the form of widespread lies accusing those who espoused the option for the poor of being communists or subversives, he said, adding that “the church was not communist nor a friend of communists.”

“But, the empire of evil, terror and lies did not understand it that way. And the persecution was unleashed like never before, making of our church, a martyrial church,” Archbishop Escobar wrote.

And that martyrial church is one that, like the death and resurrection of Christ, is a source of hope, not sadness.

Before COVID-19 brought public gatherings to a halt worldwide, celebrations for the 40th anniversary of St. Romero’s martyrdom were planned well outside of the church in El Salvador, in England and Belgium, including a Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York.

But in the time of coronavirus, bishops in El Salvador, who also had to cancel celebrations for the milestone celebration, told the faithful to find comfort in and turn to powerful intercessors in heaven — including one of their own — in a time of crisis.

“Let us invoke Mary Most Holy and St. Oscar Romero, our saint, that through their intercession we obtain the help of God,” Archbishop Escobar said.

PREVIOUS: Ease up on news viewing, set prayer routine, archbishop advises

NEXT: Forty years after his martyrdom, St. Romero influences U.S. church

Share this story