Two recent clinics co-sponsored by the Philadelphia Archdiocese have made COVID vaccinations available for several hundred persons who are deaf, deaf-blind or hard of hearing.

On May 1, the archdiocesan Office for Persons with Disabilities and the Deaf Apostolate (OPD/DA) teamed up with the City of Philadelphia and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to provide Pfizer shots at the Esperanza Community Vaccination Center, located in the Hunting Park section of Philadelphia.

[hotblock]

Three days later, a similar clinic featuring the Moderna dose was hosted by St. Kevin Parish in Springfield, Delaware County, thanks to a partnership among OPD/DA; the Communities of Don Guanella and Divine Providence (DGDP), part of archdiocesan Catholic Social Services (CSS); and the Swarthmore-based Deaf-Hearing Communication Centre (DHCC).

American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters were on hand at both events, ensuring clients received complete information about the vaccines, as well as “ease of communication,” said Marcelle Baptiste of Yeadon, who received her jab at St. Kevin.

“Had it not been set up this way, I wouldn’t have known what type of shot it was,” said Baptiste, speaking through an ASL interpreter. “I would have had so many questions, and would have left with them unanswered.”

Heather Hicks, an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), wears a face mask with a clear insert to communicate more effectively in ASL during a Philadelphia-based May 1 COVID vaccine clinic for the deaf and hard of hearing communities, organized by FEMA with the assistance of the Philadelphia Archdiocese and several partners. (Gina Christian)

The clinics were designed to eliminate such frustrations, said OPD/DA director and Immaculate Heart of Mary Sister Kathleen Schipani, who along with the various agencies coordinated the outreaches in just two weeks.

A number of the clinics’ organizers said COVID precautions have presented specific challenges for deaf and hard of hearing populations.

FEMA interpreter Heather Hicks noted masks can make it harder to express oneself in ASL, since along with hand and body movements, “part of the language is facial expression.”

For example, mouth movements (sometimes called “mouth morphemes”) can modify ASL adjectives and adverbs, conveying important detail that accompanies signs.

“Facial expressions are like the glue that holds it all together,” said DHCC executive director Neil McDevitt, voicing his responses directly to CatholicPhilly.com. “Without them, you feel like you’re missing big bits and pieces, important ones.”

Those who are hard of hearing but “don’t know sign language … rely on lip reading,” which masks also obscure, Hicks said.

Some of the difficulty for that group can be offset by masks with clear insets that show the mouth, which Hicks uses herself – but those unable to track down the modified protection often “don’t go out” to avoid anxiety and frustration in making themselves understood, she said.

That withdrawal is counterintuitive in the deaf community, said Sister Kathleen.

“Deaf people get their information in person,” she said, and social distancing has resulted in “people (being) left out of that communication” process.

P.J. Mattiacci, a regional disability integration specialist for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), worked with the Philadelphia Archdiocese to ensure members of the area’s deaf and hard of hearing communities received COVID vaccinations. (Gina Christian)

“This is the first time (in over a year) I’ve been out meeting deaf people I have not met before,” said McDevitt. “All of the social events have been essentially cancelled for the past 14 months.”

In many respects, said McDevitt, “losing your connection with your peers has been harder” for those in the deaf community.

While business, social and spiritual activities have moved online during the pandemic, not all deaf and hard of hearing people have internet access – particularly older individuals, said Sister Kathleen.

“They had a lot of difficulty getting the right information,” she said.

To bridge the digital divide, McDevitt said his organization has offered mobile computer labs for individuals lacking internet service.

Sister Kathleen also worked with Karen Leslie Henry, community relations coordinator of the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf, to announce the clinics to those who were offline.

“We got emails out to all of our groups, and then reached out to those who may not have electronic access,” said Henry.

Collaborating with faith-based partners like the Philadelphia Archdiocese is crucial in reaching “underrepresented communities” as a whole, said McDevitt, joking that he and Sister Kathleen are “sometimes joined at the hip” during projects.

[hotblock2]

P.J. Mattiacci, a regional disability integration specialist for FEMA, described Sister Kathleen – whom he has known for three decades — as “the Mother Teresa of the deaf community in the Philadelphia area.”

Speaking through an ASL interpreter, Mattiacci – a member of St. Stanislaus Parish in Lansdale – said a broad goal of addressing “equity issues” for an array of “underserved populations” was at the heart of the Esperanza-based clinic, which featured some 18 professionals fluent in ASL, including four Certified Deaf Interpreters (CDI).

The same mission has defined the large-scale vaccination efforts headed up by DGDP, whose qualified professionals staffed the St. Kevin clinic.

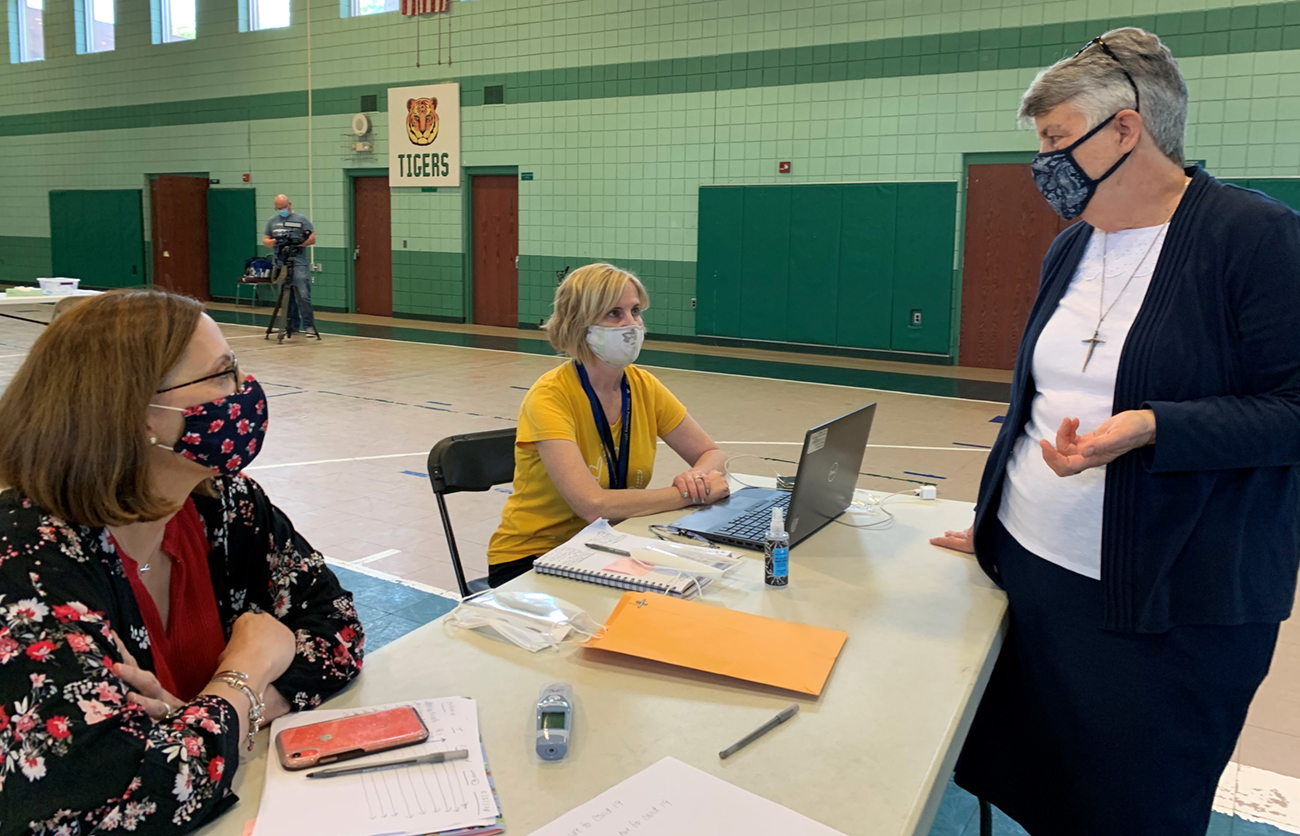

Immaculate Heart of Mary Sister Kathleen Schipani (right), director of the archdiocesan Office for Persons with Disabilities and the Deaf Apostolate (OPD/DA), speaks with Jean Calvarese-Donovan (left) and Angela Babcock of the archdiocesan Communities of Don Guanella and Divine Providence (DGDP), during a May 4 COVID vaccine clinic for the deaf and hard of hearing communities at St. Kevin Parish. (Gina Christian)

To date, DGDP – which provides a range of care to adults with intellectual disabilities — has administered more than 15,500 doses and fully vaccinated some 7,000 people, said director of nursing Angela Babcock.

As a community vaccine provider, DGDP recently staged a highly successful clinic at Lincoln Financial Field for adults with autism and their caregivers.

“We’re meeting them where they’re at,” said Babcock. “They are made to feel comfortable.”

“It’s an environment of acceptance and of knowing we support them no matter what, from the moment they walk in,” said DGDP administrator Jean Calvarese-Donovan.

Because of that approach, clients feel even more relieved after their shots, said Gina Procopio, a parishioner at Stella Maris in South Philadelphia, who brought her 16-year-old son and her brother to Esperanza.

“Today I think my son feels a little more comfortable,” said an already-vaccinated Procopio, speaking through an ASL interpreter. “He sees that a lot of people are here who can communicate with him in sign language, and if he has questions or concerns, he can get them answered.”

“We were pretty excited,” she added. “We said, ‘Let’s go, let’s do this.’”

PREVIOUS: Changes to Clergy Office, new committee, offer priests more support

NEXT: South Phila. parish dedicates shrine to addiction recovery patron

Share this story