About three years ago, Immaculate Heart of Mary Sister Virginia Paschall anxiously watched as enrollment plunged at Blessed Virgin Mary (B.V.M.) School in Darby, where she is principal.

“We’d lost 25 to 30 students,” she said. “We had a lot of families moving out of the area, and some families were leaving because of tuition.”

The decline continued despite aid from the Educational Improvement Tax Credit program (EITC) and nonprofit organizations such as Business Leadership Organized for Catholic Schools (BLOCS).

“We have parents that are just struggling day to day, paycheck to paycheck,” said Sister Virginia. “In Darby Borough itself, the poverty level is probably around 70 to 80%.”

[hotblock]

Now in her 21st year at the school, Sister Virginia was accustomed to lean times – and utterly determined to keep the doors open. For nearly two decades, she and former B.V.M. Parish pastor Msgr. Joseph M. Corley (who died in 2019) had “gone through so much to keep the school going,” she said.

“I told him, ‘I’ll be laying on the ground when the cranes come’” if the school were to close, said Sister Virginia. “We’re the only Catholic school in this area. Catholic education is really key for these students. … (It) gives them the opportunity to develop faith, morals, good skills, study habits – to have a goal for themselves.”

‘Run the business, sustain the mission’

Operating Catholic schools, especially in impoverished neighborhoods, has been a struggle for decades.

According to the National Catholic Educational Association (NCEA), U.S. Catholic school enrollment peaked in the early 1960s, which saw more than 5.2 million students enrolled in almost 13,000 schools.

By 1990, those numbers had plummeted to about 2.5 million students in just over 8,700 schools, with enrollment gradually inching up 1.3% for a few years, although schools continued to be shuttered. As of 2020, the number of schools had decreased 14.3% to just under 6,000, and enrollment had fallen by 21.3%.

Kelly Bell, principal of St. Laurentius School in Philadelphia, said the Strategic Planning Assistance Team (SPAT) program provides a sense of accountability, while fostering creative ideas for school growth. (Kelly Bell/St. Laurentius School)

The COVID-19 pandemic led many Catholic schools to permanently close, even as enrollment rebounded 3.8% after a 6.4% drop from academic years 2019-2020 to 2020-2021.

Yet most of the bump was due to pre-kindergarten enrollment, which back in February the NCEA acknowledged was “a driver of (an) overall Catholic elementary school increase.”

As of December 2021, enrollment at Philadelphia archdiocesan elementary schools was up by 1,275 students, or 4% — but regardless of trends, Catholic schools need to learn how to “run the business to sustain the mission,” said Dr. Andrew McLaughlin, secretary of elementary education for the Philadelphia Archdiocese.

And thanks to the archdiocesan Strategic Planning Assistance Team (SPAT), some 34 parish-based schools in the five-county area are doing just that, he said.

Administered through the archdiocesan Office for Catholic Education, the SPAT program educates principals in core business skills — accounting, budgeting, marketing, development – so they can make their schools “more financially sustainable and less reliant on parish funding,” wrote Archbishop Nelson Pérez in a December 2021 letter to pastors.

[tower]

Longtime Catholic education advocate Gerald Parsons – who chairs the board of the West Chester-based Foundation for Catholic Education – suggested the SPAT initiative and remains central to its implementation, said McLaughlin.

Parsons stresses the importance of “(teaching) schools to run as a business” by “(training) principals to understand balance sheets, cash flow, variance reports and budgets,” McLaughlin said.

That approach is fitting, said McLaughlin, since archdiocesan elementary school principals have more financial responsibility than their public school counterparts, whose budgets and expenditures are managed by municipal authorities.

“Our principals need to be the CEO,” he said.

With their parish schools equipped and supported by SPAT, pastors can then “become a kind of board president,” maintaining broad oversight without being mired in everyday minutiae, McLaughlin said.

One Philadelphia pastor admitted that prior to SPAT, his school’s principal would need to consult him for expenses such a “taking the eighth grade to lunch,” said McLaughlin.

For Father James Olson, pastor of St. John Paul II Parish in the city’s Port Richmond section, SPAT has conveniently assembled “talent, insight and business acumen together at one table.”

As head of a merged parish, Father Olson has seen two schools within his pastorate — Mother of Divine Grace and St. George — rebound from “precarious financial situations” due in large measure to SPAT.

Although the concept of a business model “doesn’t always fit when you’re talking about a parish or school,” he said, “there is a certain aspect in which a parish needs a business, as well as a pastoral and educational, model.”

A key goal of SPAT is weaning schools off of parish-based tuition subsidies – revenues that parishes allocate from their general funding to offset the cost of enrollment at either their own or a neighboring parish school.

“We used to get calls from principals saying, ‘I don’t know if we’re going to make payroll,’” said McLaughlin. “We now have about 12 or 13 schools that now take absolutely no subsidy from their parishes. They’re self-sustaining.”

Beyond the balance sheet

SPAT also enables school administrators to look beyond the balance sheet and focus on the future, said Kelly Bell, principal of St. Laurentius School in Philadelphia.

“Our budgeting reflects our goals in many ways, and where we see ourselves going,” she said. “SPAT provided the opportunity to have these conversations in a way they might not otherwise have happened.”

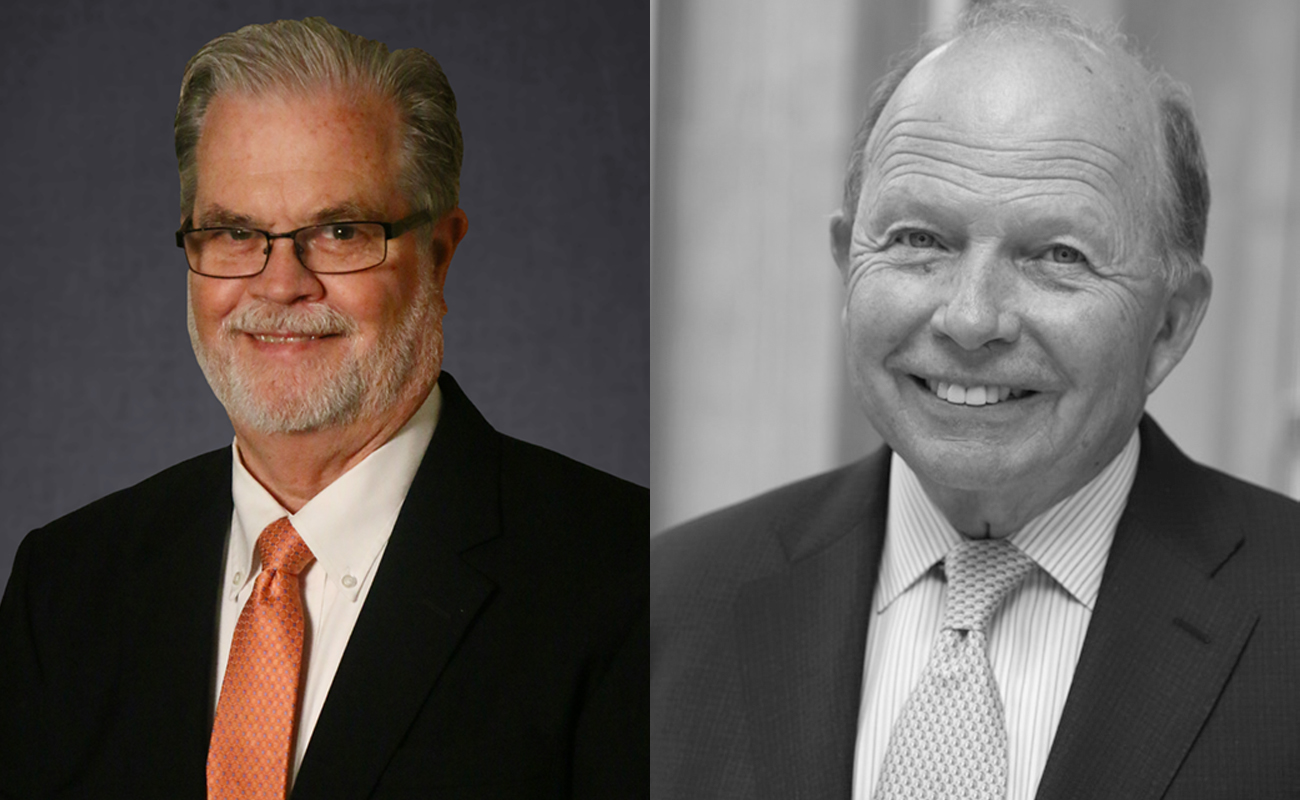

Dr. Andrew McLaughlin, secretary for archdiocesan elementary education (left) and business executive Jerry Parsons (right) developed the archdiocesan Strategic Planning Assistance Team (SPAT) to parish school finances while strengthening educational mission.(CatholicPhilly.com composite photo/Archdiocese of Philadelphia)

The program, which entails regular meetings with SPAT coordinators, ensures “a sense of accountability” to all involved, said Bell. “You have a meeting date. … With each SPAT call, I have to update them on current enrollment and what we’re projecting for next year.”

Through structure and sage advice, SPAT creates a space for envisioning a school’s future trajectory, Bell said.

“More than anything, SPAT has been a sounding board for us, allowing us to throw ideas out in the air,” she said. “We share things we’ve done, such as virtual open houses, and we’ve increased our social media marketing.”

Bell and her colleagues are also looking to “partner with local businesses” in the school’s thriving Fishtown neighborhood.

SPAT has enhanced collaboration among St. Laurentius’ administrators, she said.

“It’s eased communication; we’re prepared for meetings and are able to look at … how we can thrive amid the chaos of COVID,” Bell said. “SPAT has helped us focus.”

For Sister Virginia, SPAT’s resources have become indispensable.

“I can’t imagine what we would have done without it,” she said. “It’s really helping us right now, little by little, year by year, and it’s just realistic.”

PREVIOUS: Police rally for beloved chaplain in hospital

NEXT: St. John’s, Manayunk sets 190th parish jubilee celebration

Share this story